The mummies speak for themselves at Carnegie Science Center's new exhibit

The curators and producers behind Carnegie Science Center's new exhibit, Mummies of the World, want to make it clear that, despite opening on October 5 and containing a lot of spooky imagery, this is not a Halloween show. And they're mostly right: Mummification offers a unique (and somewhat unexpected) cross-section of disciplines, including the science of death and decomposition, anthropology, religion, and history. But it's also not without superstition.

On that last point, look to the final room of the exhibit, where the bodies of two parents and a one-year-old child are displayed in glass cases under bright lights. This is the Orlovits family, "a group of 18th-century mummies discovered in Vác, Hungary in 1994." DNA analysis of the parents, Michael and Veronica, shows evidence of severe tuberculosis, but baby Johannes has no such symptoms. In fact, he still has "baby fat," a term that is never fun to apply to a dead person. Most strikingly, Johannes' feet are bound by a small ribbon of cloth.

Jason Simmons, operations director of IMG, the company that produced Mummies of the World, explains that the bound feet are likely serving one of two purposes. First, medical science being what it was in the 18th century meant that people were sometimes falsely pronounced dead, and the bound feet could be a way to keep the patient restrained in the off chance they wake up in the middle of their funeral. Second, Simmons says that paranoia and superstition around the recently deceased would be widespread at the time that Johannes died, so the bound feet would be to keep the undead immobile. OK, that's undeniably Halloween-y, but the rest of the show is not.

The majority of the exhibit — 125 artifacts, the largest of its kind ever assembled — explores the idea of mummification with a lack of sensationalism that smartly lets the artifacts speak for themselves. The show breaks the idea down into categories: natural mummification (in which a body is preserved incidentally through a fortuitous environment); artificial mummification (an intentional process); and mummification for scientific, experimental, or medicinal purposes.

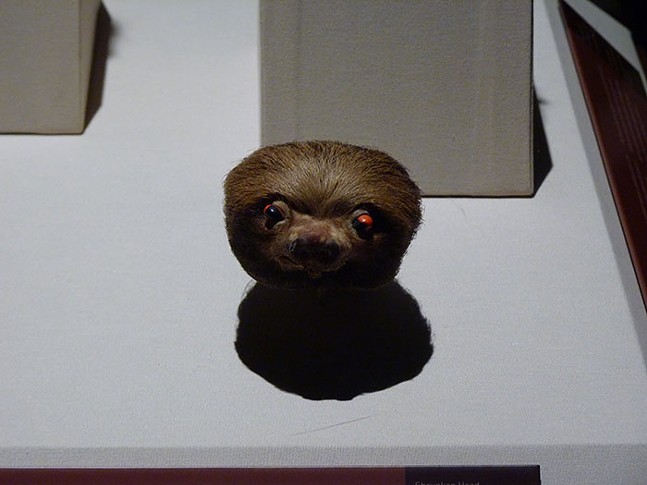

In the artificial mummification camp, there's a collection of shrunken heads, a tradition associated with South American tribes in which heads of vanquished enemies are taken as war trophies. The process generally involves removing the skull, boiling the remaining flesh and skin, filling it with a rock to retain its form, and decorating it. There is also a sloth head in this section.

The Burns Collection fills out the experimental/scientific portion, with a set of cadavers preserved by 18th-century Scottish doctor Allen Burns. In medical school in Glasgow, "Allen developed outstanding skills in dissection and devised new methods of specimen preservation, paying particular attention to the vascular system. At one time, the specimens created by Burns were considered superior to any other in the world."

Burns' work is interesting on its own, but the way the collection made its way to the States is especially memorable. It's worth looking up for the unabridged version, but essentially Burns' assistant Granville Pattison took ownership of the one-third of the artifacts after Burns' death. He was convicted of grave-robbing the next year (cadavers were hard to come by at the time) and acquitted shortly after; he then moved to America and sold the collection to the University of Maryland in 1820, who lent it out for the purpose of the exhibit.

While it's good fun to inspect these remarkable items through glass, the show thankfully allows for some tactile action. In the "What does a mummy feel like?" section, visitors can touch the different textures involved with different kinds of decomposition. Did you know that bog bones, remains preserved in a watery bog, feel "rubbery and soft"? They do.

There's a lot of fascinating information in Mummies of the World, much of it new to most of us; the exhibit is smart to include Egyptian mummification but not rely on it too heavily. What's vaguely familiar from middle school history is still remarkable and kind of jarring to witness so close up, and the unfamiliar is occasionally shocking. The success of the exhibit is in illuminating how deeply bizarre this practice is, while hinting that there's something instinctual about it to human life. Witnessing these artifacts, collected from cultures across the globe and some dating back thousands of years, points to something universal and timeless about mummification, which is both captivating and a little creepy.

On that last point, look to the final room of the exhibit, where the bodies of two parents and a one-year-old child are displayed in glass cases under bright lights. This is the Orlovits family, "a group of 18th-century mummies discovered in Vác, Hungary in 1994." DNA analysis of the parents, Michael and Veronica, shows evidence of severe tuberculosis, but baby Johannes has no such symptoms. In fact, he still has "baby fat," a term that is never fun to apply to a dead person. Most strikingly, Johannes' feet are bound by a small ribbon of cloth.

Jason Simmons, operations director of IMG, the company that produced Mummies of the World, explains that the bound feet are likely serving one of two purposes. First, medical science being what it was in the 18th century meant that people were sometimes falsely pronounced dead, and the bound feet could be a way to keep the patient restrained in the off chance they wake up in the middle of their funeral. Second, Simmons says that paranoia and superstition around the recently deceased would be widespread at the time that Johannes died, so the bound feet would be to keep the undead immobile. OK, that's undeniably Halloween-y, but the rest of the show is not.

The majority of the exhibit — 125 artifacts, the largest of its kind ever assembled — explores the idea of mummification with a lack of sensationalism that smartly lets the artifacts speak for themselves. The show breaks the idea down into categories: natural mummification (in which a body is preserved incidentally through a fortuitous environment); artificial mummification (an intentional process); and mummification for scientific, experimental, or medicinal purposes.

In the artificial mummification camp, there's a collection of shrunken heads, a tradition associated with South American tribes in which heads of vanquished enemies are taken as war trophies. The process generally involves removing the skull, boiling the remaining flesh and skin, filling it with a rock to retain its form, and decorating it. There is also a sloth head in this section.

The Burns Collection fills out the experimental/scientific portion, with a set of cadavers preserved by 18th-century Scottish doctor Allen Burns. In medical school in Glasgow, "Allen developed outstanding skills in dissection and devised new methods of specimen preservation, paying particular attention to the vascular system. At one time, the specimens created by Burns were considered superior to any other in the world."

Burns' work is interesting on its own, but the way the collection made its way to the States is especially memorable. It's worth looking up for the unabridged version, but essentially Burns' assistant Granville Pattison took ownership of the one-third of the artifacts after Burns' death. He was convicted of grave-robbing the next year (cadavers were hard to come by at the time) and acquitted shortly after; he then moved to America and sold the collection to the University of Maryland in 1820, who lent it out for the purpose of the exhibit.

While it's good fun to inspect these remarkable items through glass, the show thankfully allows for some tactile action. In the "What does a mummy feel like?" section, visitors can touch the different textures involved with different kinds of decomposition. Did you know that bog bones, remains preserved in a watery bog, feel "rubbery and soft"? They do.

There's a lot of fascinating information in Mummies of the World, much of it new to most of us; the exhibit is smart to include Egyptian mummification but not rely on it too heavily. What's vaguely familiar from middle school history is still remarkable and kind of jarring to witness so close up, and the unfamiliar is occasionally shocking. The success of the exhibit is in illuminating how deeply bizarre this practice is, while hinting that there's something instinctual about it to human life. Witnessing these artifacts, collected from cultures across the globe and some dating back thousands of years, points to something universal and timeless about mummification, which is both captivating and a little creepy.