Editor's note: This article has been updated.

It's one in a slew of spring's first hot days, and K. Chase Patterson is wearing thick black sunglasses. His students at the Urban Academy of Greater Pittsburgh in Larimer are playing in a mostly unshaded grass lot owned by the school.

Just over a mile away, leaves are sprouting on the sycamores, oaks, and Japanese cherry trees that stand at orderly intervals in front of ranch houses and bungalows. The second-wealthiest neighborhood in the city, Squirrel Hill North, boasts 1,587 street trees, and the contrast with Larimer, which has 280, is striking.

"If you live in a neighborhood that doesn't have trees, you can't climb a tree," says Patterson, the CEO of the academy.

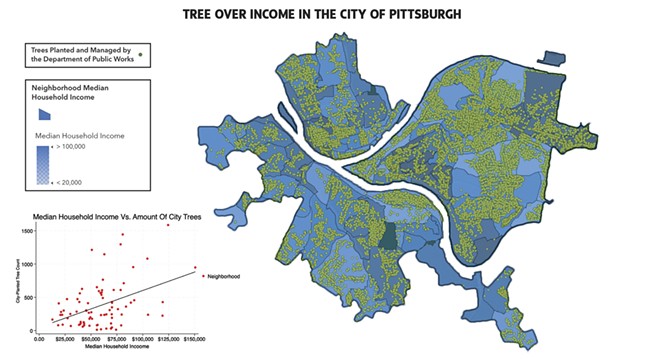

Pittsburgh City Paper mapped every street tree planted and managed by the City of Pittsburgh as of 2014 and overlaid them on a map of neighborhoods and their median household incomes recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2022. The results show that 37% of all 33,071 city-planted street trees line the streets of Pittsburgh's top 15 wealthiest neighborhoods. Meanwhile, several lower-income neighborhoods have fewer than 10.

While the city plants street trees for free upon request, residents and advocates say many people who live in lower-income neighborhoods such as Larimer, which has a median household income of $21,087, can't take the time to file a request when they have to worry about how they're going to get themselves to work or clothes for their kids.

"The case is that, if you're struggling in a struggling community, you've got to figure out how to make time to un-struggle yourself," Patterson says. "And that's just not cool when we could do so much more."

City Paper found that, for every $10,000 increase in median household income, a given neighborhood's tree count increases by an average of 56. Urban trees can lower local temperature, reduce air pollutants, and increase residents' immune system functioning, according to a report by The Nature Conservancy.

Pittsburgh is not alone. According to the 2021 Tree Equity Score, 522 million trees need to be planted and grown across urbanized America to combat inequalities in forestry distribution, with a focus on low-income, historically neglected neighborhoods.

According to City Forester Lisa Ceoffe, the city routes street-tree requests to the Department of Public Works Forestry Division, which will then perform a site analysis to determine whether they can plant a tree in one of its two planting periods in the spring or fall.

Ceoffe says the department is aware of the disparities in street tree planting and partly attributes them to limited staff and a stretched budget, which have caused past requests to go unfulfilled and may have discouraged people from filing again.

"Our job is to listen now and to find out what we can do about changing their mindset," Ceoffe says. "Or, if they don't want a tree, then we don't plant it. We're certainly not going to do something that somebody doesn't want when we have so many people that want a tree."

According to the current street tree inventory, Squirrel Hill South, a residential neighborhood colloquially grouped in with Squirrel Hill North, has the most street trees in Pittsburgh, at 2,396, while Glen Hazel, a neighborhood encompassed by an affordable housing community of the same name, has some of the fewest, at only five. Both share a border in Pittsburgh's fifth district.

District 5 City Councilmember Barbara Warwick says that city resource distribution often follows income lines among the nine neighborhoods she oversees. Squirrel Hill South has a median income of $67,726, while Glen Hazel has a median household income of $25,792.

"In more affluent neighborhoods, people have more time to understand the processes [within] the city," Warwick says. "They have more time to call their council person and complain."

The difference isn't only felt in a lack of trees. Warwick notes there are 20 speed humps in Squirrel Hill South and none in Greenfield and Hazelwood — neighborhoods again separated by a few miles but by greater than $20,000 in median household income. (Update April 26 10:00 a.m.: The City of Pittsburgh notified CP that the city plans traffic-calming projects in both neighborhoods this summer).

According to Patterson, cars often screech down Larimer Ave. without a speed hump in sight. As an educator, father, and Larimer community member, he says, "I’m always worried, always. It’s the nature of my business."

Speed humps, speed cushions, speed tables, raised crosswalks, and more fall under the city's traffic calming program — each available upon a resident's request, according to the City of Pittsburgh website.

"[Trees] are like every resource, whether it's traffic calming or rec centers, you name it," Warwick says. "Unfortunately, that's just kind of been the trajectory of the city."

Ceoffe says that the 31 affordable housing communities managed by the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh (HACP) have historically received fewer street tree plantings, even compared to the under-resourced neighborhoods under the city's direct purview.

"Historically speaking, [The HACP] were responsible for managing their own properties," Ceoffe says. "Under Mayor [Ed Gainey], we've been connecting closer with them, doing these types of plantings, getting more involved with the leadership there to see what we can do to bring the trees to the neighborhoods."

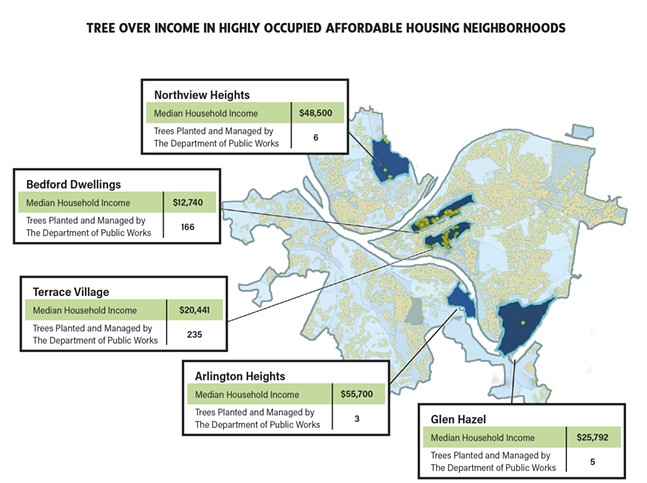

CP identified five neighborhoods encompassed by or majorly occupied by affordable housing communities with substantially lower tree counts relative to their median household incomes.

Arlington Heights, Glen Hazel, Northview Heights, Bedford Dwellings and Terrace Village are all housing communities with tree counts below the 44th percentile relative to their median household income, with half below the 10th percentile.

Northview Heights, a 455-unit public housing community tucked into Pittsburgh's North Side, has only six street trees, while its median household income of $48,500 suggests it should have 310.

"People don't ever look at public housing as supposed to be home, a community," Olivia Bennett, a resident of Northview Heights, says. "When people think of [public housing communities], they don't think we should make it beautiful."

Bennett, who served on the county council from 2020 to 2023, says many people who live in Northview Heights cope with the mental health conditions that disproportionately affect people with low incomes. She says, "[Post-traumatic stress disorder] is most definitely a thing up here," and without trees, it's harder for those struggling to find a sense of calm.

When she's stressed, Bennett says she'll often sit by her bathroom window to watch the large Eastern white pine in her backyard move with the wind.

"To just watch the leaves go back and forth does reduce stress; in mental health, that would be called grounding," Bennett says. "That's definitely a way to reduce stress and be more present and mindful in the moment."

Michelle Kondo, a research social scientist with the United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, says being around trees increases mood and lowers stress levels and blood pressure. In her research, Kondo found that being around green spaces significantly reduces feelings of depression and "worthlessness."

In a recent study where Kondo measured gun violence rates at vacant sites in Philadelphia before and after a team planted greenery and cleaned up the area, she says she found a decrease in shootings.

"Changes in the social atmosphere of the community can be the pathway or the mechanism by which we might see changes in or reductions in crime or violence," Kondo says.

Bennett says the corner of Chicago St. and Mt. Pleasant Rd. in Northview Heights, where a public safety center now sits, used to be "one of the most dangerous corners in America."

While the neighborhood's crime rate has improved, Bennett says beautification efforts would help Northview Heights shrug off its reputation as a "violent and scary place."

"Planting trees and beautifying: that also gives that message that there's life up here, that there’s people up here that matter," Bennett says. “They also will feel like they matter, and so we can also reduce some of the negative things that we see in the community today."

The Forestry Division is currently pursuing the Equitable Street Tree Investment Strategy, officially adopted by a proposal from the Shade Tree Commission, a quasi-governmental entity, in 2020 to increase the urban canopy in neighborhoods federally described as "marginalized by underinvestment and overburdened by pollution," Ceoffe says.

Under the Equitable Street Tree Investment Strategy, the department and a coalition of partner organizations reach out to community groups in cohorts of underserved neighborhoods to patch shade cover inequalities without first requiring a resident to file a direct request. The initiative considers the effects of heat island, air quality, and other factors.

The initiative went into effect in 2021, but its impact remains to be seen. The Forestry Division is currently refreshing its inventory, and Ceoffe predicts the total number of street trees will have gone up from 33,071 in 2014 to roughly 60,000 today.

Even with 60,000 street trees potentially planted throughout the city, Patterson says he still sees the disparity whenever he passes through Squirrel Hill and when he comes to work in Larimer.

Patterson says the way his K-5 students at the Urban Academy view themselves is impacted by how Larimer presents itself. Surrounded by front yards filled with rubber tires baking in the sun and scattered vacant lots, trees could go a long way.

"When these trees are filled with leaves, what you don't see is the decay; you see the potential," Patterson says, motioning to the unfurled trees sparsely lined down Larimer Avenue. "Trees are indicative of what is possible. And when you don't have a tree highlighting your possibilities, all you have are the bad stories to tell."

While the Shade Tree Commission selects 10 underserved neighborhoods every year to fill gaps in planting and maintenance, Patterson says that, as far as he knows, work hasn't yet been done to increase street trees in Larimer — so he's taking it on himself.

Patterson says in the coming months, the Urban Academy, which owns 20 parcels of land in Larimer, will begin lining all its properties with trees.

“I wish I didn't have to do this work, absolutely,” Patterson says, scratching his chin. “But you know, it’s what I'm doing. It’s what I’ve got to do.”