Sophie Masloff was Pittsburgh’s first woman mayor. She entered politics at a time when racketeers had unfettered access to the highest city and county offices. When an aging associate of Meyer Sigal — a mobster with a criminal record that included gambling, bribery, and smut — claimed that Masloff had helped to fix gambling cases while she worked as a court clerk, Pittsburgh City Paper had to ask, “Did Sophie Masloff have criminal ties?”

The allegations that Masloff was doing favors for mob friends from inside the Allegheny County Courthouse didn’t pan out. Yet, while digging into previously unexplored corners of the former mayor’s life story, some surprises did emerge. These include a more nuanced childhood than the rags-to-riches story recounted in Masloff’s biography.

Masloff’s mother was an alleged bootlegger and her cousins were wealthy racketeers and labled slumlords. There was much more to the grandmotherly Masloff than the appealing story about pulling herself up by her garters to become one of the most powerful and pioneering women in Pittsburgh history.

Masloff grew up in a single-parent Hill District home. Her mother, twice married and twice widowed, was a Romanian Jewish immigrant who settled in a close-knit ethnic community. Jennie Friedman, Masloff’s mother, arrived in the United States in 1902 with her first husband, Samuel Nieberg. They were part of a large migration of mostly impoverished Romanian Jews called fusgeyers in Yiddish, which means walkers or wayfarers.

Jennie’s first husband died in 1915 and she remarried a widower neighbor, Louis Friedman, in 1917. Sophie was born three months later.

Friedman worked in a variety of jobs after emigrating in 1892. Between 1910 and 1923, the year he died, Friedman worked as an insurance salesman, courthouse clerk and watchman. His half-brother Jacob built homes and invested in Hill District real estate.

For a time, the brothers worked in the real estate business together until they had a falling out. “They were on such bad terms that Jacob Friedman did not visit his half-brother during the eighteen months that [he] was dying from cancer,” wrote Louis Friedman’s attorney in court papers.

Many Romanian Jews went into real estate after settling in Pittsburgh, said Eric Lidji, Director of the Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives at the Heinz History Center.

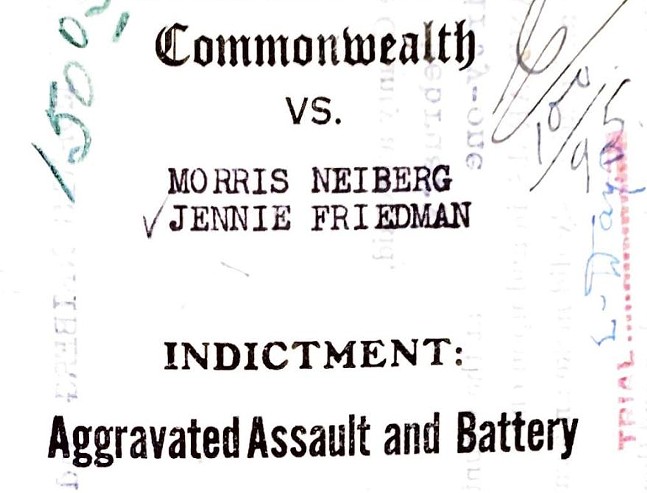

Jennie Friedman became a bootlegger before her husband died. Her alleged crimes were described in newspaper articles published in 1921 and 1931. Police seized moonshine, beer, and wine in a March 1931 raid on the Friedman home. One month before the raid, Jennie and her son Morris were arrested and convicted of aggravated assault and battery.

These episodes and the Friedman family’s wealth are absent in all published accounts documenting the former mayor’s life. Friedman’s 1923 estate included $55 in “household goods,” $137 in cash, and real estate worth more than $4,000 ($72,000 in 2024).

“Sophie never talked much about her childhood. It was just too painful. It wasn't as if she was ashamed of her past,” wrote historian Barbara Burstin in her self-published 2019 book, “Sophie: The Incomparable Mayor Masloff.”

Burstin was unaware of the bootlegging and assault conviction. “Absolutely not,” Burstin told City Paper when asked if she knew about Jennie Friedman’s exploits. “I never knew that.”

The historian confessed that she hadn’t been interested in Masloff’s early life and that the period wasn’t part of her book research. “I didn't think it was relevant to Sophie,” Burstin said. “I didn't go into her family background. I'm just going into Sophie.”

She also didn’t know that Masloff had an uncle. “Who is he?” Burstin replied when asked about Jacob Friedman.

Burstin also didn’t know about Jacob Friedman’s daughter Hilda, and Meyer Talenfeld, the man she married in 1927. The Talenfelds, also Romanian Jews, had been in real estate and the bail bonds business since the 1930s.

Meyer and his brothers Sam and Edward used their real estate holdings to secure bail bonds that they wrote for numbers racketeers. They were among a small pool of bail bonds entrepreneurs who repeatedly found themselves on the wrong side of the law. The charges mainly involved using the same property to simultaneously secure multiple bonds.

The FBI once described Meyer Talenfeld as “an associate of leading Pittsburgh hoodlums,” but he was much more than an associate.

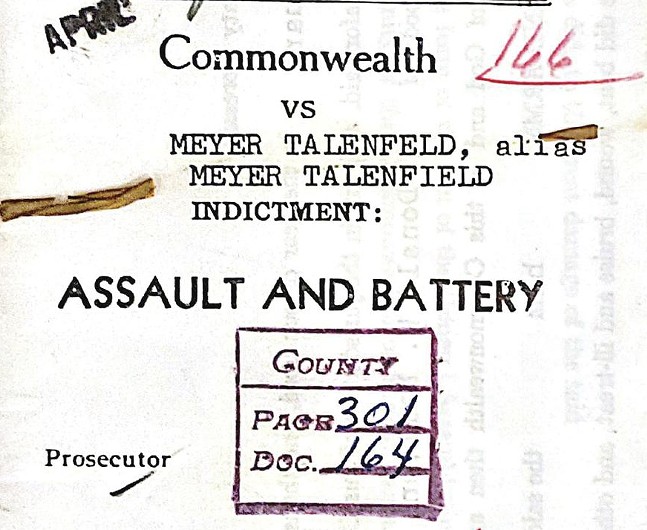

Between 1933 and 1977, Meyer Talenfeld was arrested multiple times. The charges included disorderly conduct (for calling a police officer a coward) in 1933; attempting to bribe an assistant district attorney (1940); receiving stolen goods (1951); and, burglary (1976).

Meyer Talenfeld assaulted a Hill District Catholic priest in 1967. Donald McIlvaine was one of several civil rights leaders protesting against the Talenfelds. According to newspaper accounts, during one of the protests Talenfeld shoved the priest and used “abusive language.” The protestors claimed that the Talenfelds were charging high rents and not maintaining their properties.

In one episode, protestors took boxes of trash to the Talenfelds’ Uptown office. They carried signs that read, “Talenfeld Lives” and “Slumlords are not dead,” the Pittsburgh Press reported.

Pittsburgh Courier photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris photographed picketers outside Talenfeld offices and their East End home. The large inventory of properties that the Talenfields acquired to support their bail bonds business had become some of the city’s most disinvested slums.

The Talenfelds and Friedmans lived in a close-knit community that spawned some of the city’s best-known racketeers, like Sigal. He was born in Pittsburgh to Romanian parents who owned a Hill District grocery store and who sold bootleg liquor and numbers tickets on the side.

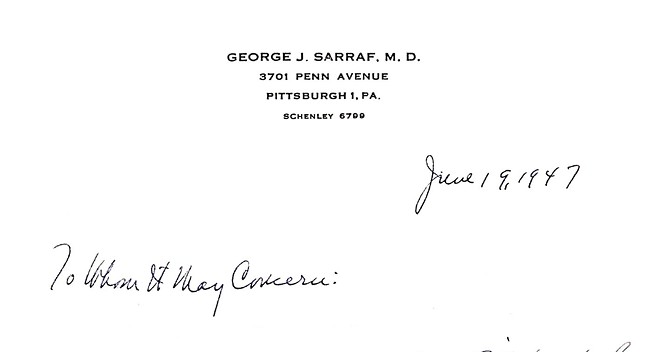

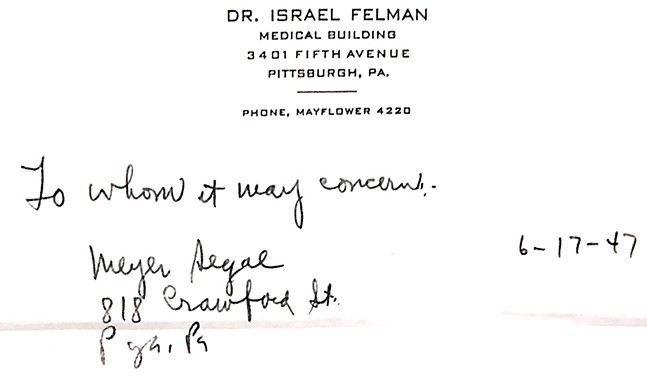

Sigal’s arrests included numbers gambling, bribery, and possessing obscene literature. A regular fixture in Allegheny County criminal courts, local newspapers dubbed him “Sickman” Sigal for getting doctors to write notes excusing him from court.

In 1961, he and another convicted racketeer, Frank Parrotto, founded the Daily Juice Company. Four years later, Sigal and other mobsters testified in federal court about their protection payoffs to Pittsburgh Police Assistant Superintendent Lawrence Maloney. By then, Sigal was one of the city’s most recognizable criminals.

When a close associate of Sigal’s claimed that Masloff, a Sigal family friend, had done favors for the mobster, it was not such an outlandish allegation considering the city’s history. The associate, who requested anonymity due to the sensitive nature of his story, said that Sigal had told him that Masloff, who had worked in the Allegheny Courthouse “assignment room,” could steer gambling cases to particular judges who would either dismiss the cases or hand out lenient sentences.

On its face, the story seemed plausible. But it had some holes. The biggest one is assignment room clerks like Masloff only picked juries, not judges. There simply wasn’t any proof, other than the second-hand account originating from Meyer Sigal, a well-documented liar who died in 2000.

No, Sophie Masloff wasn’t mobbed up. But her family, however, was. About the only thing the late former mayor may be guilty of is poor choices in the people whom she befriended and keeping secrets about her family.