Fifty years ago, the South Side was an old mill neighborhood with a dwindling population. Its main drag, East Carson Street, was cavitated by vacant storefronts. Few people saw its potential to be something else. But one of them was Charlie Samaha, and that was no small thing.

Samaha moved to Pittsburgh from New York in 1966; he fell in love with the South Side and spent some two decades working hard, and loudly, to make it better. He was a millworker, a landlord, a merchant, an actor, a gadfly and a busybody. Today, Samaha is remembered mostly by South Siders of a certain age, who call him a peerless local character — and perhaps the key force behind the revitalization that eventually turned the South Side into one of the city’s busiest neighborhoods.

Those long-timers turned out in force on the evening of Sept. 13, in the grassy parklet at 11th and East Carson streets, to rededicate a memorial to Samaha, who died in 1991 at age 68. About 50 celebrants convened by the South Side Community Council recalled Samaha’s legacy and feted the return of a gravestone-like marker to a space like the ones Samaha so often cleaned up, right around the corner from an antique store he ran. The granite stone was heedlessly discarded four years ago by young volunteers renovating the parklet; it was salvaged by architect Jerry Morosco, who met Samaha when he moved to the South Side in 1986.

Speakers at the brief gathering included Kathleen Zimbicki, one of the numerous artists, gallerists and antique-sellers whom Samaha lured to the South Side, often promising free or low rent in one of his several buildings. “There was only one Charlie,” said Zimbicki, whose Studio Z art gallery lasted until 2003.

“He really was the unofficial mayor of South Side,” said Keith Attwood, who traces the South Side location of his goldsmithery, established in 1976, directly to Samaha’s powers of persuasion.

Arthur Ziegler, the influential co-founder and president of Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, recalled Samaha’s eagerness to include buildings he owned in PHLF’s pioneering program to renovate Victorian façades on East Carson.

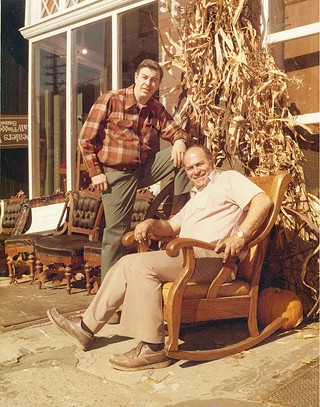

Samaha, a Louisiana native of Lebanese descent, worked here at mills including J&L Steel, where he did maintenance work, according to his long-time friend and business partner Fred Flugger. Samaha’s best-known creation was the South Side Antiques, Arts & Crafts Association (SACA). The group dated to the early ’70s; its 1989 brochure lists 50 businesses, all but a few gone now, lost to time or rising rents. But starting a decade before community-development groups like the better-known South Side Local Development Corp. and South Side Community Council even existed — and long before outsiders came there to party — these businesses and SACA’s marketing made South Side a regional destination.

Gene Ricciardi, a former South Side community activist and city councilor who is now a city magistrate, says Samaha’s vision of redeveloping around artists and architecture was then unique. As Samaha told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 1973, “The South-side [sic] is artistic and old, the buildings are available at a reasonable price, and this part of town is handy to every place else in the city.”

But Samaha wasn’t quite a proto-Richard Florida: It’s hard to imagine the “creative-class” theorist pulling the stunts that made Samaha so aggravating to some. “He was a no-BS guy,” says Ricciardi. Many, for instance, recall Samaha sweeping sidewalks and presenting the trash (or even a bill) to the owners of adjacent storefronts. “He didn’t do that to be mean-spirited,” says Ricciardi. “He was trying to build community spirit and community pride.”

Samaha had many sides. To beautify vacant lots, he drew in the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (which co-owns the 11th Street parklet with Lamar Advertising); he also did some acting, notably playing a store-owner in the Pittsburgh-shot 1986 comedy Gung Ho.

While some old-timers lament how by the late ’90s the bar scene had eclipsed the South Side’s arts-and-culture community, it’s unclear how Samaha would have felt. After all, he was the guy who in the ’80s defended Mario’s South Side Saloon — the community’s first “fern bar” — from neighbors who said it brought trouble.

Others note wryly that Samaha’s stated goal of remaking the South Side into the French Quarter North has in some ways come true.

Samaha’s best-known bit of theater involved a coffin. Back when East Carson’s blacktop was moribund, he procured a man-sized wooden box, set it in a huge pothole and laid down inside. He invited press, and the resulting publicity quickly got the thoroughfare repaved. At last Wednesday’s gathering, longtime South Sider and local poetry eminence Michael Wurster read his poem “A Pothole Big Enough for a Coffin,” in which he recalled the coffined Samaha — “a man you couldn’t push over” — clutching an American flag and brazenly pulling off the feat “at rush hour on a Friday afternoon.”

“That’s Charlie,” said someone in the crowd.