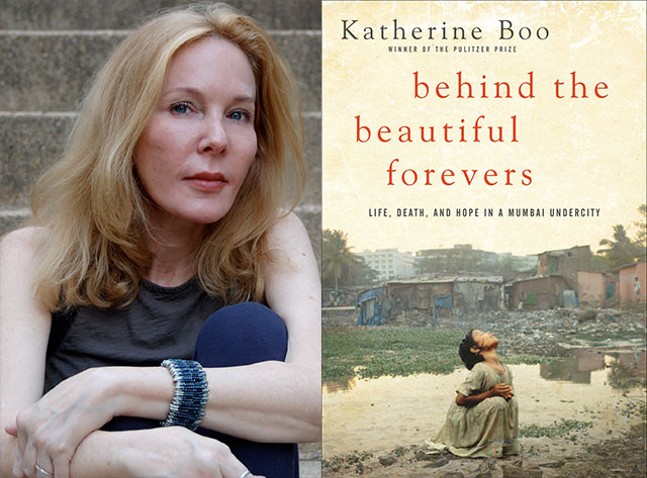

Katherine Boo's resumé boasts numerous awards, including a Pulitzer Prize for public service during her tenure at the Washington Post, a MacArthur Fellowship, and a National Magazine Award for feature writing.

But the Washington, D.C. native's crowning achievement is Behind the Beautiful Forevers (Random House), winner of the National Book Award for nonfiction in 2012. Boo's look at an impoverished community in India cements her place as one of the most accomplished investigative journalists working today.

Boo, who will appear Oct. 22 as a guest of Pittsburgh Arts & Lecture's Ten Evenings series, recently took time to answer a few questions for City Paper.

Much of your work is focused on telling the stories of people who are ignored or overlooked, whether they are intellectually disabled living in group homes, the poor in Oklahoma, or the residents of slums of Mumbai. Do you think that we feel guilty we live in a world that allows people to exist in these conditions, so we tend not to acknowledge their existence?

Here in the U.S., I think the root is anxiety as much as guilt. A decade of economic expansion hasn’t exactly produced a collective sense of blithe wellbeing, what with student loan and credit card debt at record highs, labor's share of GDP still in the tank, and elite politicians pitting groups of people who should have common causes against each other. If you’re under duress yourself, you’re more likely to write off the humanity of people whose conditions are worse than your own. Or maybe you start blaming those people for their hardship — all the better for keeping your own conscience clear. The ubiquity of that mental process is one of the things I write to undermine. If a reader can see individuals in marginalized, stereotyped communities as persons in full — persons questioning, doubting, judging and acting just as imperfectly and idiosyncratically as the reader herself — maybe it becomes a little harder for that reader to ignore the structural injustices that stomp on their talents and possibilities. That’s part of what I’ll get up to during my talk on Monday, too — getting beyond sometimes remote and abstract “conditions” by sharing the thoughts and self-portraits of young people in India and the U.S. who are in the thick of the struggle right now.

What motivates you to tell these stories? Why do you look where many look away?

I sometimes want to look away, too! Just last week, that climate change report drove me straight back to bed. But the people whose lives I document generally keep me going. As it stands, most of what happens to low-income and marginalized people gets lost to the public record, and much of what those individuals say, especially about the conduct of the powerful, gets disbelieved. So even when I’m frustrated by my ability to do justice to a given reporting project, I still sense the point of the work. Spending sustained time in marginalized communities, listening deeply and investigating patterns of injustice from the bottom up will at least bring a few drops of water to a very dry lake.

It's been six years since Behind the Beautiful Forevers was published. Have there been any tangible improvements in the lives of the residents of Annawadi since then? Are you in touch with any of the people you wrote about?

I’m still in touch with the people I wrote about, and many other families in the community too. Among the small changes residents note since the book came out are that more students are finishing quality high schools and going to college (royalties funded better educational options); politicians have become slightly more responsive than in the past to urgent concerns like water shortages; and gratuitous police brutality seems to have diminished once officers realized someone with a video camera might be wandering around. But I feel squeamish describing these fragile gains, given the force of what hasn’t much changed in six years, including the public health crisis and widespread discrimination against migrants, low-caste families, women, and others. Moreover, just as in the United States, the jobs that seem abundant in government employment statistics aren’t steady enough or well-paying enough to keep hard-working people out of poverty. (That disconnection between jobs and security is something I’ll be exploring on Monday, too.)

You're given an unlimited budget and a long deadline to write about anything you want. Where do you go and what story do you tell?

In that thrilling scenario, I’d join the team of international investigative journalists examining the human and political consequences of this age of dark money and global corruption. The Panama Papers and other crucial leaks have exposed some of those individuals who are hiding an estimated $7.6 trillion from taxation. It’s more painstaking and dangerous to uncover what that hidden circulation of money secretly buys, and how inside deals made with impunity affect the quality of air and water; human rights and human dignity; the legitimacy of democracies themselves — I could go on. It’d be cool to live in a world where we can better trace how currently unaccountable wealth is shaping the values and priorities of nations, but I guess that takes us right back to the invisibility question you began with. It’s hard to even begin to challenge what’s deeply unfair or outright wrong in our societies without seeing the consequences clearly.