Throughout Pittsburgh, there are bridges, museums, theaters, and other monuments named after famous locals, whose contributions made indelible marks on everything from sports to science to the arts. So, you would think Lois Weber, a Pittsburgh native who went on to make hundreds of silent films and became a key figure in the founding of Hollywood, would have her own memorial.

After decades in near obscurity, Weber will finally receive her due on June 13 when the Heinz History Center presents a special dedication ceremony and night of programming.

Lois Weber: Film Pioneer will celebrate Weber’s 140th birthday with the unveiling of a historical marker outside the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh-Allegheny branch. The commemoration continues at the Heinz History Center with a conversation between actress, filmmaker, and Turner Classic Movies host, Illeana Douglas, and Shelley Stamp, a California-based film historian and professor who wrote the book Lois Weber in Early Hollywood.

Heinz History Center curator, Lauren Uhl, learned about Weber a few years ago while doing research on the local film industry. “I’ve always been interested in who was from Pittsburgh that made history in Hollywood,” says Uhl. “Here was this incredibly accomplished famous woman from Pittsburgh — how come nobody’s ever heard of her?”

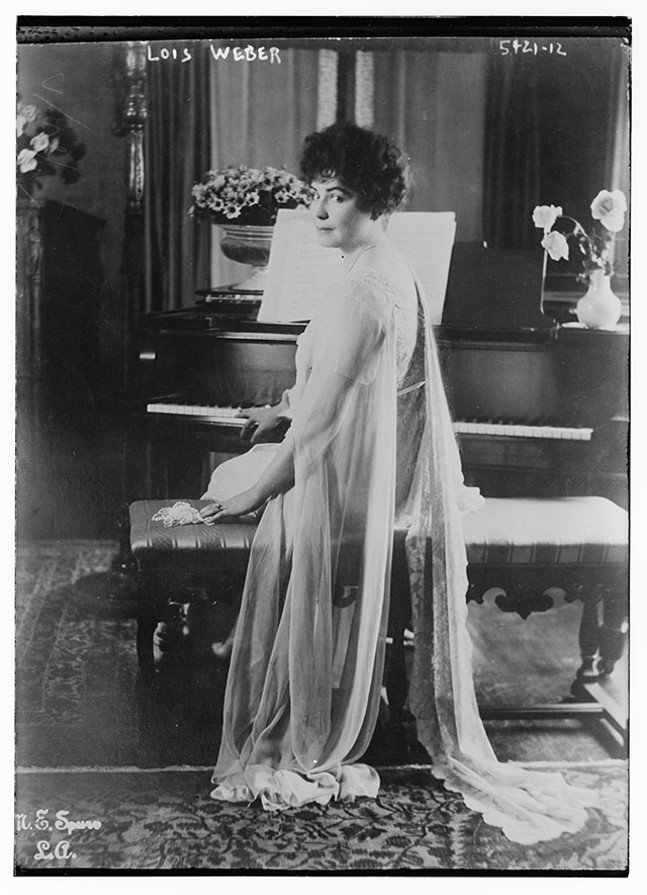

Born on Federal Street in Allegheny City (now known as Pittsburgh’s North Side) in 1879, Weber became one of the country’s first female film directors, often working as a team with her husband, Phillips Smalley. In a career that spanned a quarter of a century and included founding her own production company in Los Angeles, Weber wrote, directed, produced, and performed in more than 200 films, many of which no longer exist.

One of her surviving films, the 1913 release Suspense, will screen during the event. The 10-minute long story about a woman and her child being terrorized in their own home has stood the test of time, even screening at the Museum of Modern Art in 2013. The film has also been cited for helping to lay the groundwork for the modern thriller and horror genres.

“There’s a lot in it that talks about her as a filmmaker — the angles, the cuts, the way she’s doing things,” says Uhl.

Since the 1970s, Weber and other early women filmmakers have slowly made their way back into the public consciousness, including in the 2018 DVD/Blu-ray box set, Pioneers: First Female Filmmakers, which was executive produced by Douglas and curated by Stamp.

Weber’s career has become more defined by the moralist films she made addressing a variety of controversial social issues, including capital punishment in The People vs. John Doe (1916), drug abuse in Hop, the Devil’s Brew (1916), and poverty and wage equity in Shoes (1916).

Uhl believes these films were heavily influenced by Weber’s upbringing in Pittsburgh, where she was encouraged to pursue music as a talented pianist, and practice missionary work by her devout evangelical Christian family.

“Unlike some other celebrities who may have incidentally been born here … she really was formed here,” says Uhl, adding how Weber’s religious and artistic backgrounds were “very much reflected in her films” and “inform the filmmaker that she becomes.”

However, these films also complicate Weber’s legacy, especially the two that explore women’s reproductive issues. While The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1917) is a decidedly pro-birth control tale inspired by Margaret Sanger, the film that came before it, Where Are My Children? (1916), has been viewed as an anti-abortion film that some critics see as supporting eugenics. (Sanger supported eugenics.)

Even so, Uhl believes that Weber’s main goal with these films was to engage people in civil discussions.

“Whether or not you agree with her evangelical point of view, she was making films that she felt had a point,” says Uhl. “She felt that these were important topics to be discussed civilly.”

Uhl hopes the marker and Heinz History Center event serve as an adequate tribute to Weber, who she sees as an important figure in both film and women’s history.

“I’m anxious to reintroduce her to her own hometown, let alone the greater world,” says Uhl.