Factory Installed delves into real places and digital spaces

The source material is not entirely accessible, which is partly the point

Ezra Masch’s video installation “Stations”

FACTORY INSTALLED

continues through May 28. Mattress Factory, 500 Sampsonia Way, North Side. 412-231-3169 or mattress.org

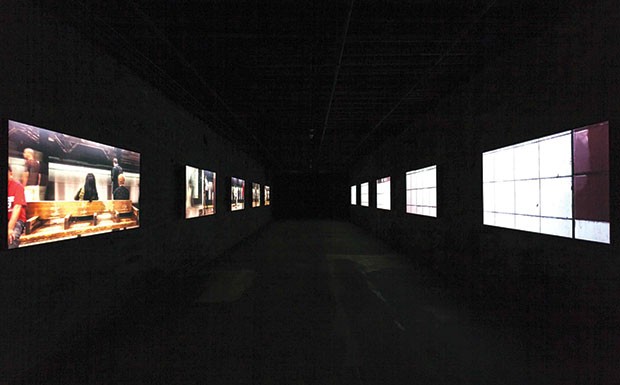

In the darkened space of the basement gallery at the Mattress Factory, the sounds of the MTA subway are instantly recognizable. Depending on when you enter, the images might be fairly still, with only people in motion, or an abstract blur of light and sound. “Stations,” a multi-channel video, plays on 10 screens — five on one long wall and five on the opposite. Edited by Ezra Masch from simultaneous footage shot by riders with their own cell phones from 10 different windows on the train, the installation makes one feel like a passenger on a subterranean ride (albeit sans rats, bad smells and subway “showtime” dancers).

The 10 screens of “Stations” are laid out based on the distance between train windows. At first glance, what seems like a single take slowly reveals itself as an amalgam of separate images. The installation, part of the museum’s Factory Installed series, is a study in both abstraction and realism. Much like a cubist or futurist painting, multiple images are here synchronized into a parallax view that depends not only on the position of the observer/recorder but on that of the observer/viewer. The complexity is further enhanced by the fact that the image both speeds by as an abstraction and then slows to reveal figuration and realism as the train comes to a stop, people enter or exit, and station signs along the No. 6 line become visible — Canal, Spring, Bleecker and Astor.

The dysynchrony of group perception is here reconfigured to form a concert of light and sound formulated by both digital and mechanical technology. It gives one pause to contemplate this particular juncture, when our technological evolution has us increasingly dependent on both physical and virtual tools.

Similar thoughts are conjured when looking at the work of Christopher Meerdo, titled “Active Denial System.” In our current digital milieu, when it takes no time at all for an image to travel the globe, Meerdo ponders the ethical issues surrounding image sharing, consumption, manipulation and hacktivism. Like Masch, Meerdo explores a space between mechanical and digital, abstraction and figuration. Five contorted abstract “figures” populate his installation. Low to the ground and oddly shaped and colored, they resemble the fanciful abstractions of Franz West. Yet the source material is quite different and far more ideological, serious and not entirely accessible, which is partly the point.

Meerdo extracts non-specific digital data from police body-cam pursuit videos and global protests, then uses an algorithm to turn shapes and ghost images into irregular sculptures through a 3-D modeling technique called photogrammetry. The sculptures are covered in reflective fabric; visitors are encouraged to take pictures using their flashes, which results in a dark photograph depicting large hunks that sparkle like fool’s gold.

Across the room, a video piece by Meerdo, called “metadata,” is a montage of images, poetry and music that forms a statement about universal and personal grief across three large screens upended into a formidable vertical shape.

By using digital composites, both Meerdo and Masch introduce nonlinearity and skepticism. Stephen Bram does the same using an entirely different medium. Employing sheetrock, timber, paint and fluorescent lights, he manipulates the gallery space itself. “Third Floor West gallery 500 Sampsonia Way” is a study in perspective. Here Bram considers points in space and creates an abstraction that is recognizable as a room but with unfamiliar odd angles. Some walls meet at a triangular point that might be at home in a Frank Lloyd Wright modular house, such as Kentuck Knob, but as a “white cube” gallery, these tight spaces prove awkward. These details underscore the fact that the room itself is the artwork. What at first seems like a bare space, with peculiarities, becomes symbolic of a deep and long-lasting conversation regarding abstraction, illusion, representation, idealism, architecture, modernism and postmodernism. Ultimately it questions the art object itself and the authority of the gallery and the museum.

“The Great Illusion,” by Mohammed Musallam, while sharing some themes with the others, is the most literal of the four installations. The room-sized installation, which smells strongly of olive oil, consists of a bed of olive leaves bordered on all sides by barbed wire embedded with stamped passport pages. A jumble of barbed wire overhead holds passport covers folded to resemble paper airplanes. Although it is reminiscent of work created back during the culture wars, when many artists were focusing on multiculturalism and identity politics, “The Great Illusion” is notable for the fact that now, in an era of white rage in the United States, works like this are still relevant. Palestinians remain under occupation with limits to their freedom and human rights, and all Arabs are stereotyped as terrorists.

While the installations in this second part of Factory Installed (the first is in the museum’s annex) are not intended to fall under a uniting theme, they are all in some way interpreting aspects of navigating space, whether literal, personal, political, virtual, abstract or concrete.

The 10 screens of “Stations” are laid out based on the distance between train windows. At first glance, what seems like a single take slowly reveals itself as an amalgam of separate images. The installation, part of the museum’s Factory Installed series, is a study in both abstraction and realism. Much like a cubist or futurist painting, multiple images are here synchronized into a parallax view that depends not only on the position of the observer/recorder but on that of the observer/viewer. The complexity is further enhanced by the fact that the image both speeds by as an abstraction and then slows to reveal figuration and realism as the train comes to a stop, people enter or exit, and station signs along the No. 6 line become visible — Canal, Spring, Bleecker and Astor.

The dysynchrony of group perception is here reconfigured to form a concert of light and sound formulated by both digital and mechanical technology. It gives one pause to contemplate this particular juncture, when our technological evolution has us increasingly dependent on both physical and virtual tools.

Similar thoughts are conjured when looking at the work of Christopher Meerdo, titled “Active Denial System.” In our current digital milieu, when it takes no time at all for an image to travel the globe, Meerdo ponders the ethical issues surrounding image sharing, consumption, manipulation and hacktivism. Like Masch, Meerdo explores a space between mechanical and digital, abstraction and figuration. Five contorted abstract “figures” populate his installation. Low to the ground and oddly shaped and colored, they resemble the fanciful abstractions of Franz West. Yet the source material is quite different and far more ideological, serious and not entirely accessible, which is partly the point.

Meerdo extracts non-specific digital data from police body-cam pursuit videos and global protests, then uses an algorithm to turn shapes and ghost images into irregular sculptures through a 3-D modeling technique called photogrammetry. The sculptures are covered in reflective fabric; visitors are encouraged to take pictures using their flashes, which results in a dark photograph depicting large hunks that sparkle like fool’s gold.

Across the room, a video piece by Meerdo, called “metadata,” is a montage of images, poetry and music that forms a statement about universal and personal grief across three large screens upended into a formidable vertical shape.

By using digital composites, both Meerdo and Masch introduce nonlinearity and skepticism. Stephen Bram does the same using an entirely different medium. Employing sheetrock, timber, paint and fluorescent lights, he manipulates the gallery space itself. “Third Floor West gallery 500 Sampsonia Way” is a study in perspective. Here Bram considers points in space and creates an abstraction that is recognizable as a room but with unfamiliar odd angles. Some walls meet at a triangular point that might be at home in a Frank Lloyd Wright modular house, such as Kentuck Knob, but as a “white cube” gallery, these tight spaces prove awkward. These details underscore the fact that the room itself is the artwork. What at first seems like a bare space, with peculiarities, becomes symbolic of a deep and long-lasting conversation regarding abstraction, illusion, representation, idealism, architecture, modernism and postmodernism. Ultimately it questions the art object itself and the authority of the gallery and the museum.

“The Great Illusion,” by Mohammed Musallam, while sharing some themes with the others, is the most literal of the four installations. The room-sized installation, which smells strongly of olive oil, consists of a bed of olive leaves bordered on all sides by barbed wire embedded with stamped passport pages. A jumble of barbed wire overhead holds passport covers folded to resemble paper airplanes. Although it is reminiscent of work created back during the culture wars, when many artists were focusing on multiculturalism and identity politics, “The Great Illusion” is notable for the fact that now, in an era of white rage in the United States, works like this are still relevant. Palestinians remain under occupation with limits to their freedom and human rights, and all Arabs are stereotyped as terrorists.

While the installations in this second part of Factory Installed (the first is in the museum’s annex) are not intended to fall under a uniting theme, they are all in some way interpreting aspects of navigating space, whether literal, personal, political, virtual, abstract or concrete.