Three installation artists explore the spaces we inhabit

The Mattress Factory’s Factory Installed tackles ecology, learning environments … and drywall

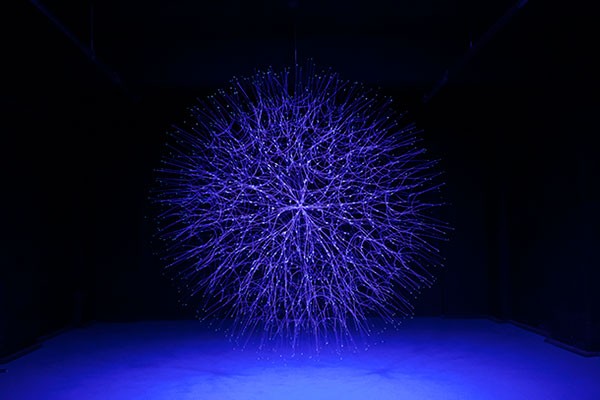

Bill Smith’s “Spherodendron”

FACTORY INSTALLED

continues through July 3. Mattress Factory, 500 Sampsonia Way, North Side. 412-231-3169 or mattress.org

Asked where they live, most humans would name a city, state or town — some bordered entity itself created by other humans. In various ways, the three artists in Factory Installed, at the Mattress Factory, question our assumptions about where we live or work, and how we think about those spaces.

Bill Smith’s critique is both the broadest and the most programmatic. His heady Mattress Factory installation includes: a projected video of The People of the Forest, a feature-length 1988 Discovery Channel documentary, based on research by Jane Goodall, about 20 years in the life of a family of chimpanzees in Tanzania; a small-screen, text-heavy short video about the importance of studying nature in cities; and the rather spectacular “Spherodendron,” a large wire sculpture that models such complex systems as the internet, the layered cellular structure of the cerebral cortex, and indeed the universe itself.

In wall text, the Illinois-based artist writes that he wants to demonstrate the “interconnected, interdependent … character of the world.” The short video’s animated icon is a kestrel, a type of hawk that thrives in cities. The video argues that “urban wilderness” can be a functioning ecosytem if we help it be, and touts the benefits of pervious pavement (which prevents stormwater runoff), trees and vegetated roofs. “Nature is of supreme import,” the text asserts at one point, only to add later, “Man reigns supreme.” Also this: “You are an animal.”

Enter the chimps. People of the Forest provides soulful closeups of these sociable, charismatic creatures, and if the voiceover narration makes humanizing assumptions about its subjects (“He had become a spoiled brat”) — well, you watch animals with whom we share 98.8 percent of our DNA without anthropomorphizing ’em. And so when Smith offers you a panel embedded with an electronic button next to the words “I am a great ape,” you push it, then enter the Spherodendron chamber. A voiceover offers some background, the lights change, the sculpture rotates. But when “Spherodendron” glows green in a darkened room, the effect is stunning, evoking just the sense of wonder Smith is after: We are one with this planet, and with these fellow life forms, of whom we’ve taken such poor care.

With his work “Faculty,” Dutch artist Rob Voerman is more concerned with the great indoors. Inside a day-lit room he’s build a second, self-contained habitat, a structure partly inspired by Pittsburgh’s own Cathedral of Learning but long rather than tall. It’s half scrap wood and (echoing Thomas Hirschhorn’s “Cavemanman,” from the 2008 Carnegie International) half a mad patchwork of cardboard and packing tape.

Voerman’s wall text says that “Faculty” is a “hybrid between dwellings, caves, the primitive hut and the cathedral,” and that it’s partly meant to serve as a small classroom environment. But certain details feel ironic. With its Plexi windows and portholes that you can see out of (if you’re inside) but not into (if you’re out), the interior feels more like a submarine, or an adolescents’ clubhouse, and it’d be easy enough to hit your head on the wooden bracing. What are those two slightly ominous tabletop vises for? Why does one entrance have a door while the other is doorless? Why is the whole thing listing to one side? And what sort of precarious community could one build here, anyway?

Lisa Sigal’s “Break It Down” at first suggests a purely aesthetic experiment. The Brooklyn-based artist’s medium and subject alike is drywall, small sections of which are cut into geometric forms and then painted with geometric shapes, mostly in tones of cream, tan, black and the dull gray of drywall backing paper. Along one gallery wall leans a large frame of 2-by-4s, as if for a new wall; behind it, two small sections of drywall lean on the gallery’s brick wall.

It all struck me as a bit, well, dry, until I read Sigal’s statement, which explained that, using plaster, she’d made all the drywall in the show herself. That explained the eccentric textures in some of the pieces (patterns like riverbed sand) and also raised the irony that Sigal is offering us painstakingly crafted versions of a consumer product whose processed uniformity is one with its ubiquity. Furthering the funhouse playfulness, one of the pieces in the show incorporates screen prints of photos of an under-construction apartment block; and the walls that some of these pieces are hung on are the gallery’s own false walls (veiling the structural brick), even if they’re made of “real” drywall.

Sigal writes that she seeks to “examine illusion as a counterpoint to permanent and impermanent structures in urban space.” And indeed, as with all the spaces we inhabit, there’s more here than first meets the eye.

Bill Smith’s critique is both the broadest and the most programmatic. His heady Mattress Factory installation includes: a projected video of The People of the Forest, a feature-length 1988 Discovery Channel documentary, based on research by Jane Goodall, about 20 years in the life of a family of chimpanzees in Tanzania; a small-screen, text-heavy short video about the importance of studying nature in cities; and the rather spectacular “Spherodendron,” a large wire sculpture that models such complex systems as the internet, the layered cellular structure of the cerebral cortex, and indeed the universe itself.

In wall text, the Illinois-based artist writes that he wants to demonstrate the “interconnected, interdependent … character of the world.” The short video’s animated icon is a kestrel, a type of hawk that thrives in cities. The video argues that “urban wilderness” can be a functioning ecosytem if we help it be, and touts the benefits of pervious pavement (which prevents stormwater runoff), trees and vegetated roofs. “Nature is of supreme import,” the text asserts at one point, only to add later, “Man reigns supreme.” Also this: “You are an animal.”

Enter the chimps. People of the Forest provides soulful closeups of these sociable, charismatic creatures, and if the voiceover narration makes humanizing assumptions about its subjects (“He had become a spoiled brat”) — well, you watch animals with whom we share 98.8 percent of our DNA without anthropomorphizing ’em. And so when Smith offers you a panel embedded with an electronic button next to the words “I am a great ape,” you push it, then enter the Spherodendron chamber. A voiceover offers some background, the lights change, the sculpture rotates. But when “Spherodendron” glows green in a darkened room, the effect is stunning, evoking just the sense of wonder Smith is after: We are one with this planet, and with these fellow life forms, of whom we’ve taken such poor care.

With his work “Faculty,” Dutch artist Rob Voerman is more concerned with the great indoors. Inside a day-lit room he’s build a second, self-contained habitat, a structure partly inspired by Pittsburgh’s own Cathedral of Learning but long rather than tall. It’s half scrap wood and (echoing Thomas Hirschhorn’s “Cavemanman,” from the 2008 Carnegie International) half a mad patchwork of cardboard and packing tape.

Voerman’s wall text says that “Faculty” is a “hybrid between dwellings, caves, the primitive hut and the cathedral,” and that it’s partly meant to serve as a small classroom environment. But certain details feel ironic. With its Plexi windows and portholes that you can see out of (if you’re inside) but not into (if you’re out), the interior feels more like a submarine, or an adolescents’ clubhouse, and it’d be easy enough to hit your head on the wooden bracing. What are those two slightly ominous tabletop vises for? Why does one entrance have a door while the other is doorless? Why is the whole thing listing to one side? And what sort of precarious community could one build here, anyway?

Lisa Sigal’s “Break It Down” at first suggests a purely aesthetic experiment. The Brooklyn-based artist’s medium and subject alike is drywall, small sections of which are cut into geometric forms and then painted with geometric shapes, mostly in tones of cream, tan, black and the dull gray of drywall backing paper. Along one gallery wall leans a large frame of 2-by-4s, as if for a new wall; behind it, two small sections of drywall lean on the gallery’s brick wall.

It all struck me as a bit, well, dry, until I read Sigal’s statement, which explained that, using plaster, she’d made all the drywall in the show herself. That explained the eccentric textures in some of the pieces (patterns like riverbed sand) and also raised the irony that Sigal is offering us painstakingly crafted versions of a consumer product whose processed uniformity is one with its ubiquity. Furthering the funhouse playfulness, one of the pieces in the show incorporates screen prints of photos of an under-construction apartment block; and the walls that some of these pieces are hung on are the gallery’s own false walls (veiling the structural brick), even if they’re made of “real” drywall.

Sigal writes that she seeks to “examine illusion as a counterpoint to permanent and impermanent structures in urban space.” And indeed, as with all the spaces we inhabit, there’s more here than first meets the eye.