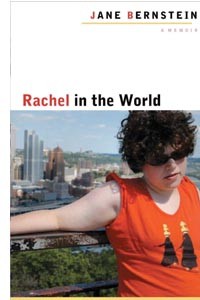

Rachel in the World: A Memoir

By Jane Bernstein

University of Illinois Press, 267 pp., $26.95

Jane Bernstein's Rachel in the World: A Memoir is a sequel to 1988's Loving Rachel, a book about raising a special-needs daughter. The readiest audience for the new book, which details Bernstein's unflagging efforts to integrate her child into society, would seem to be the families of other special-needs individuals. But Rachel in the World is also interesting as an expression of that peculiarly American notion of the pursuit of happiness.

Rachel, born with a host of physical and mental impairments, was 5 when Loving Rachel was published. Bernstein and her family were living in New Jersey at the time; they moved to Pittsburgh in the early '90s. But the new book, which follows Rachel through her 22nd birthday, is mostly about Bernstein, and her fight to get Rachel medical care, schooling, a job and -- most challengingly -- a home away from her mother's home.

Bernstein, a professor of English and creative writing at Carnegie Mellon University, is a solid, funny and honest writer. She never lets her love for her daughter impede her candor. We learn that Rachel is legally blind, and that she matured so slowly that she received growth hormones at age 8 and needed estrogen just to go through puberty. We also learn -- and are indeed never allowed to forget -- that cohabitating with the developmentally disabled is no endless trail of hugs and sweet life-lessons. During Rachel's childhood, Bernstein wondered if her daughter would ever speak; later, she became aggrieved that the girl, with her "nonstop meaningless questions," wouldn't shut up.

Bernstein makes us feel her own sadness at the moment when -- prompted by reading a school curriculum for her 18-year-old daughter that includes "setting the table" -- she is finally driven to verbalize the thought: "She really is retarded." Yet there's little if any sentimentality here. With lengthy verbatim repetitions of Rachel's own insistent repetitions, Bernstein communicates the annoyance and the psychological drudgery that she often felt, and the strain of living with a daughter who demanded her own home but would likely never be cabable of living solo.

A wider picture emerges, too. Bernstein acutely observes the social dynamics of such phenomena as: cute special-needs kids receiving less sympathy from society once they mature into less-cute special-needs teens; the oddness of dealing with government-funded home aides -- strangers who become surrogate (if temporary) family; negotiating the future with a daughter who wants to move out even though she's wholly unmindful of diet, hygiene and personal safety; and the toll this all takes on Bernstein's writing, her marriage (her husband, who suffered from chronic liver disease, dies during the course of the book) and her older daughter.

The pith of the book, however, finds Bernstein grappling with the system, or lack thereof, for getting people like Rachel employed and sheltered as adults. Promising options come and go, including a seemingly idyllic sojourn at an Israeli kibbutz. But even in the wake of the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act, it's been an era of tight funding for such housing and employment programs. So everything would have been rough sledding and long waiting lists even if Bernstein weren't so choosy: At one point, she questions a possible "shared living arrangement" for Rachel (essentially adult foster care) because the host family slept in sometimes and watched lots of television.

Bernstein is reflective enough to question her own standards, too. And she's sensitive enough to locate her plight in such universal dilemmas as some people's expectation that one will care for one's grown dependent children -- or aging parents -- even at a cost to others in the family. And surely no one who reads Rachel in the World can help wondering: If it's this tough for Bernstein -- smart, educated and affluent enough that the family had a vacation cottage in Maine -- what's it like for poor people facing similar challenges?

Much of Rachel in the World takes place in the wake of 1994's "Contract with America" -- a Republican Congress's vow to scale back government, and with it many supports the disabled community relied upon. Group homes, for instance, were not an option for Rachel because of defunding. (Nor could Bernstein afford the 24-hour staffing a privately rented apartment for Rachel would require.)

Bernstein asks, rightly, why the richest nation on earth has such a hard time providing for some of its most vulnerable citizens. Implicit in her question -- and in the book as a whole -- is the idea that life for the disabled and their families should be better than it is, or at least closer to some norm. More than once, Bernstein adduces the Constitution: "Since my daughter was unable to pursue her own happiness, who would help her realize this 'inalienable' right? Or did the U.S. Constitution not apply to her?"

But the "pursuit of happiness" doesn't appear in the Constitution -- the law of the land. Rather, it's in the Declaration of Independence, which, though its the title resonates wryly with the themes of Bernstein's story, serves as a statement of purpose rather than a national rulebook. And Bernstein's factual error reflects our national mythology: The hope that we'll have housing and jobs for the disabled, for instance, seems somehow linked to that Shining City on a Hill offer of a good life for all.

Bernstein's story takes place at an historic pinch-point: when the disabled, though (thankfully) no longer relegated to institutions, remain unintegrated into the wider world. Here, the promise of freedom paves a narrow path to its realization, and one mother's expectations seem to sharpen her travails in fulfilling them.