For nearly all of our estimated 200,000 years on Earth, human beings were nomadic or semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers. We lived off the land, used stone tools and spent most days in the company of the few dozen people in our band. Our lifestyle began changing only some 11,000 years ago, with the beginnings of agriculture and settled communities. And only during the past few millennia did humans create the large, urbanized societies we now take for granted.

Actually, contemporary humans consider normal an even newer way of life, one characterized by nation-states, heavy global trade, constant technological change ... and pre-sweetened breakfast cereals.

But as Jared Diamond argues, we're not normal. Like a polyester shirt on an Ice Age tribeswoman, we're WEIRD — Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic. And that bias blinds us to wisdom that traditional people derived from what Diamond calls "thousands of natural experiments" over countless generations.

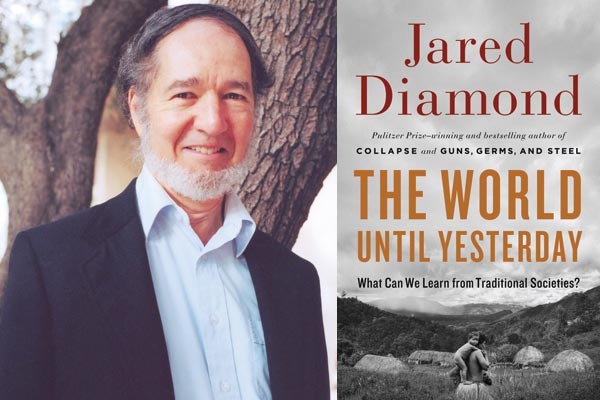

In his new book, The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies? (Viking), Diamond provocatively compares our modern lifestyle to the ways of 39 traditional societies around the world: Africa's Kalahari San, Australian aborigines, the Yanomamo of the Amazon. Some still live much like our Stone Age ancestors. The 75-year-old Diamond draws many of his examples from New Guinea and neighboring islands, where he's regularly taken research trips for nearly 50 years.

Whether for his own scientific interest or to conduct environmental surveys for either government agencies or Chevron Corp., Diamond was visiting New Guinea to study birds. But during his 26 sojourns, he also spent much time among tribespeople and villagers. He mined that experience in his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1997 book Guns, Germs and Steel and 2005's Collapse, and which he explores even more fully in The World Until Yesterday.

Although we moderns are anatomically identical to Stone Agers past and present, Diamond notes, we live very differently. Traditional folk seldom encounter strangers, for instance, and thoroughly distrust them. And they make everything they need, rather than buying it. But as he documents, many traditional practices seem to aid human well-being. Among them: on-demand breast-feeding; nonpunitive child-rearing; restorative justice and mediation (rather than our adversarial, right-or-wrong justice system); bi- or multilingualism; and the low-salt, low-sugar diets our bodies were actually made for, instead of our unhealthy alternative.

In a phone interview with City Paper from a speaking-tour stop in Seattle, Diamond says that he hopes The World Until Yesterday can help dissolve our unrealistic love/hate relationship with traditional societies.

"We in the West," he says, "go back and forth between, at the one extreme, regarding traditional societies as primitive brutes from whom we can learn nothing" and, alternately, idealizing and romanticizing them — even ignoring the infanticide, and the killing and abandonment of elders, that occurs in some societies.

In Collapse, Diamond sounded an environmental alarm, noting that any one of a dozen global crises — from climate change and deforestation to overpopulation — might be enough to undermine modern civilization, as smaller-scale crises once did to Easter Islanders and the Greenland Norse. Such examples contrast starkly with Diamond's example of New Guinea's highland farmers, who have practiced a form of sustainable agriculture for some 7,000 years.

While environmental issues remain pressing, The World Until Yesterday doesn't address them explicitly. And in fact, Diamond says, despite their relatively miniscule environmental impact, traditional societies are not always green role models.

"It's not the case that traditional people are wise stewards of their environment who never exterminate anything. They can make mistakes," he says. "They have less potent firepower for exterminating species, but nonetheless they've often managed to do it with their stone axes and clubs."

The most environmentally sustainable traditional societies, he says, are those that have secure land and tenure there. Such conditions give them both a stake in what happens to the land and the ability to prevent outsiders from exploiting resources (like fish or forage) they are managing for themselves.

Diamond does agree, however, that traditional societies' emphasis on community responsibility — to the point of discouraging the celebration of individual achievement — helps them manage resources better than we do.

"We in the West, with our emphasis on the individual, tend to feel those resources are there for me to harvest, and never mind whether it depletes resources for other people," he says. "In a traditional society, where everybody depends on each other and you know all your neighbors, the resources are there for everybody, and that then is more of a recipe for managing the resources in the interests of the community."

Diamond himself is carefully managing information about the nature of his Jan. 14 talk here at Drue Heinz Monday Night Lectures. "It will be a surprise that will delight you and my listeners," he promises.