When Ernest “Pud” Gooden died in 1934, The Pittsburgh Courier lamented the loss of “one of the greatest young ball players that the Pittsburgh district ever produced.” The paper eulogized “that prince of Goodfellows” whose “sinewy arm could throw with the accuracy of a rifle” and whose “hawk-like eyes could solve the cleverest pitchers’ most deceptive deliveries.”

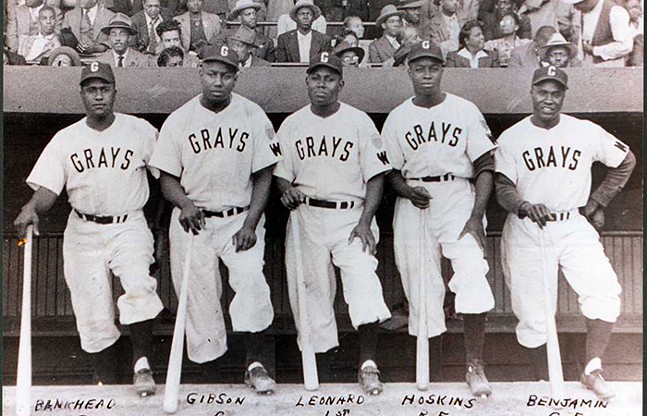

Gooden played ball for the biggest teams in the Negro Leagues, including Pittsburgh’s Homestead Grays, the Toledo Tigers, and the Detroit Stars.

But if you were to make a pilgrimage to Gooden’s grave today, you would be hard-pressed to find a place to lay a baseball in honor of this sports legend. Gooden is buried in an unmarked plot in Monongahela Cemetery.

The same is true of Sam “Lefty” Streeter, who Satchel Paige called the best pitcher he had ever known, as well as Emmett “Scotty” Bowman, the one-time Philadelphia Giant who pitched in the sandlots and barnstormed with the best. Their names shared rosters with the greats — Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, and Cool Papa Bell. But despite their fame, Streeter, Bowman, and dozens of other Negro Leaguers are buried in cemeteries throughout Southwestern Pennsylvania, with no markers to tell us their names, much less their stories.

The Josh Gibson Foundation wants to right this wrong.

The foundation, established by Gibson’s descendants in honor of the legendary Homestead Grays player, is dedicated to honoring the legacy of Negro League players. Using a list compiled by author and teacher Vincent T. Ciaramella, the foundation has identified more than 30 players buried in unmarked graves in Southwestern Pennsylvania. The Foundation wants to give these players the recognition they deserve by crowdfunding through donations on Paypal to place markers at their graves. On Aug. 12, the first marker will be laid at the grave of Helen Mason, Gibson’s wife who died in childbirth in 1930, and whose grave is near Gibson’s in Allegheny Cemetery.

“The Josh Gibson Foundation celebrates everyone who was a part of the Negro Leagues,” Foundation volunteer Christian Cox tells Pittsburgh City Paper. “Negro Leagues stars like Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige are comparatively well-known, but the vast majority of players are not. By placing these markers, the Foundation hopes to help keep their legacies alive.”

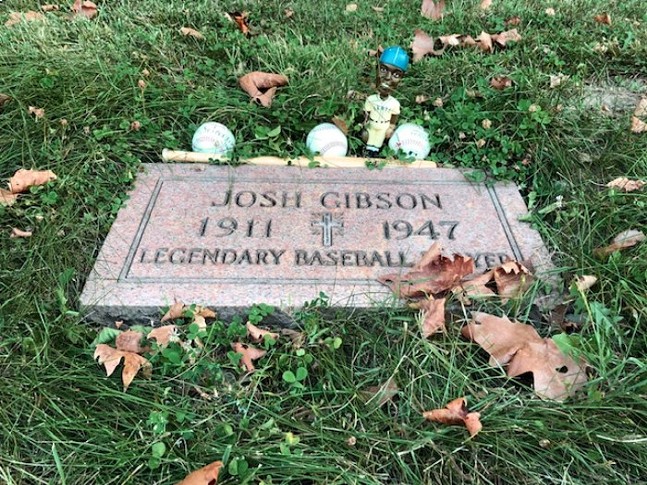

Today, Gibson is listed among notable burials in the cemetery and a marker off the main path points visitors to his grave. You might even find an array of offerings — baseballs and bats, notes, and Gibson bobblehead dolls — on the flat plaque bearing his name. But this wasn’t always the case.

Gibson died in 1947, just a few months before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in major league baseball. Yet, despite his status as a Negro League standout, he was laid to rest in an unmarked grave.

It wasn’t until after Gibson was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1972 that a marker was finally placed at his resting place with the support of Pittsburgh Pirates players.

Sean Gibson, the Gibsons’ great-grandson and executive director of the foundation, sees the placing of markers as more than just a gesture. For him, the markers honor the legacy of his ancestors and give peace to those who paved the way for his generation. Sean says he hopes that the families of the other Negro League players will “feel the same excitement” that he felt when the marker was placed at his great-grandfather’s grave.

In recent years, the discovery of Black cemeteries that had been paved over to make way for sports arenas, such as Tropicana Field in Tampa, have highlighted the deep racism and inequities that defined not only the lives of Black Americans but also their deaths. From God’s Little Acre in Newport, Rhode Island to Oak Union Colored Cemetery in Florida, significant efforts are underway to restore and preserve African American cemeteries across the country.

Gibson and many other Negro League players, though, were not buried in African American cemeteries. Though the major cemeteries in Pittsburgh were not segregated by policy, the color line that often defined their lives was also visible after their deaths.

Gibson’s grave, for example, is located in Section 50 of Allegheny Cemetery. Unlike the palatial memorials to the Pittsburgh elite in other parts of the cemetery, this quiet hillside is dotted by flat plaques that are barely visible to the casual passerby.

Many of the people buried here were, like Josh and Helen Gibson, heroes of the Great Migration, people who left the Jim Crow South only to encounter a different set of racial biases in northern cities. For Black ball players, this meant significantly lower pay than white counterparts, and the inability to stay or eat in the same establishments as white players who they often handily outshone on the field.

This inequity and disrespect in death — as in life — was something that writer Zora Neale Hurston, author of Their Eyes Were Watching God, rallied against.

In 1945, just two years before Gibson died, Hurston wrote to American sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. Dubois to suggest the creation of a cemetery for the “illustrious Negro Dead.”

She envisioned a 100-acre park in Florida with trees in bloom year-round. She imagined a place where Frederick Douglass and Nat Turner and other Black heroes would be honored and celebrated, and where no one would be forgotten.

In the letter to Dubois, she wrote: “Let no Negro celebrity, no matter what financial condition they might be in death, lie in inconspicuous forgetfulness. We must assume the responsibility of their graves being known and honored.”

Hurston’s vision was not only a celebration of the history of Black excellence, it was a rejection of the forced forgetting of Black stories and histories.

She knew, too, that this remembrance was as much for the living as for the dead: “You must see what a rallying spot that would be for all that we want to accomplish and do.”

Sadly, Hurston’s plans were never realized, and when she died in 1960, she was similarly buried in an unmarked grave. But Hurston’s vision remains vital.

By recognizing Negro League players like Gooden, Streeter and Clark, the Gibson Foundation hopes that new markers will do just what Hurston envisioned.

They will not only honor the players, but organizers say the markers will also serve as an opening for the future, so that the stories of Pud Gooden, Sensation Clark, and other Negro Leaguers might inspire the next generation of Black excellence.

The initiative “isn’t just for baseball fans,” Cox says. “This is the story of our city. It’s about our shared humanity and connections to our past. Any unmarked grave is a missed opportunity to know something about the people who lived here before us and made this region what it is today.”

Honoring a legend

Josh Gibson was known as the “Black Babe Ruth,” but some might argue that it is more fitting to call Babe Ruth the “White Josh Gibson.” Known as one of the best power hitters in history — it is said that the sound of his bat hitting the ball was like the sound of a mighty tree falling in the forest — Gibson was a star in the Negro Leagues, including local stints as a member of the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays.

In 1994, recognizing the need to honor the legacy of the Negro Leagues and to support the “next Josh Gibson,” the player’s descendants established a private, nonprofit foundation in the Steel City. At first, the Josh Gibson Foundation was committed to creating sports facilities and baseball fields for young Pittsburghers. Over the years, the Josh Gibson Foundation expanded its mission to include a variety of programs including, mentoring, tutoring, and athletic programs.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Gibson’s induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame, the second Black player after Satchel Paige to receive this honor. The Foundation will mark this anniversary with a series of events and new projects, including the Josh Gibson Memorial Markers Project, to keep advancing awareness of Gibson and all those who played in the Negro Leagues, while also paving the way for the next generation of legends.

For more information about the Josh Gibson Foundation, visit www.joshgibson.org, or email Sean Gibson at sgibson@joshgibson.org for more information about the Josh Gibson Memorial Markers Project.