Doug Oster and Jessica Walliser have now written the book on organic gardening.

"It was well known how wonderful were the hanging gardens of Pittsburgh. ... When the time came that it was no longer expedient to maintain the larger furnaces, Pittsburgh awoke to find its beauty its source of livelihood. Certain skyscrapers, now without tenants, were given over unreservedly to horticulture. ... If the wind blew in the right direction, the citizens of Youngstown, or Morgantown, or Cleveland could smell the fragrance of Pittsburgh from afar. ... They would say to one another, "Oh to be in Pittsburgh, in beautiful Pittsburgh."

-- Haniel Long, "How Pittsburgh Returned to the Jungle"

In 1926, Haniel Long penned a satire about Pittsburgh, his native city. In it, a "millionaire nurseryman lobbying for his private gain" sneaks a bill through Harrisburg requiring Pittsburghers to decorate their windows with flowers. The state legislature passed the bill "[i]n the confusion which prevails at the close of a tiresome session," Long wrote. In the process, they accidentally turned an industrial powerhouse into a new Eden.

Long was gently mocking both Pittsburgh and its politicians. But he may also have been prophesying. Decades after he wrote the piece, the mills did shut down ... and Pittsburgh began sprucing up, reclaiming riverfronts and building bike paths.

And as in other cities, Pittsburghers are taking up urban farming -- planting crops on small plots not just to beautify neighborhoods, but to help feed residents, too.

The best known of these sites is Mildred's Daughters, a five-acre hilltop spread in Stanton Heights that conducts tours and classes in urban farming. The land has been a working farm since the late 1800s, and today it employs sustainable agricultural practices, selling its products to local restaurants and residents. But in recent years, smaller farms have been cropping up everywhere.

Urban farming "is really taking on a life of its own," says Miriam Manion, the executive director of Grow Pittsburgh, a nonprofit group that teaches about, and advocates for, urban farming within the area. "There is just all kinds of energy around it. It seems like the stars are aligned for it to take off."

As you'll see elsewhere in these pages, vacant lots across the city are being plowed under and replanted. Tiny farms are thriving in the husks of old factories, while writers plant seeds of their own.

Over in Wilkinsburg, meanwhile, a greenhouse produces heirloom tomatoes and other seedlings, shipping them to hundreds of customers. If you're wondering how you could have missed seeing a greenhouse in one of the region's most urban areas, there's a reason: It's in Mindy Schwartz's basement, down with the hot-water pipes and bicycles.

"This is cathartic for me," says Schwartz, bent over a tray in which she is depositing tiny seeds with names like "Earl of Edgecomb" and "Mortgage Lifter."

"One little seed in each little hole," Schwartz says, to herself as much as to anyone.

The basement lies beneath a renovated apartment building Schwartz co-owns; as she deposits the seeds, the sounds of opera filter down from one of the apartments above. This is the nursery for Garden Dreams, Inc., which supplies produce to local cafes and customers from all over the region and beyond.

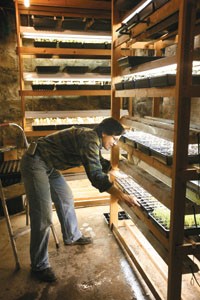

Once the tray is seeded, Schwartz will move it to one of the half-dozen wooden racks behind her, each of which holds a series of trays underneath growing lamps set at adjustable heights. Heat emanates from the pipes overhead -- Schwartz has left them uninsulated -- and in fact the basement is a Department of Agriculture-licensed greenhouse. On a cold spring weekend like this, it's also far cozier than the barren plots in Schwartz's backyard, still waiting for the year's first planting.

"I didn't set out to build an urban farm," Schwartz admits. "I would just stand on my back porch and look at the lot next door and think, 'I could have a big garden over there.'"

Compared to Mildred's Daughters, her acreage is small. It's a quarter-acre lot, much of which was formerly occupied by pair of dilapidated houses. But it has become "a sort of mini-farm model," Schwartz says. It has certainly become an example of urban farming's challenges -- and the rewards it can bring.

Acquiring the land was the easy part. As with many urban plots, the soil was contaminated with lead and other pollutants -- including abandoned pom-poms, dolls, and 2-by-4s left behind by generations of residents. Before she could plant a single seed, Schwartz had to dig troughs four feet deep, clearing away the trash and contaminated soil. And then she had to find new soil to replace it with.

She didn't have to look far. Wilkinsburg's public-works department had tons of the stuff -- the residue of years' worth of street cleaning.

"It was gorgeous," Schwartz says of the moldering pile of leaves, disgorged by street-sweepers. "Like 100 percent leaf compost. But it was also filled with sneakers, Coke cans, anything that had been sucked up from the street."

Schwartz arranged for the borough to bring the compost in an "endless series of dump trucks." Using a grate as a sifter, she filtered the trash from the mulch ... a job she did by hand and shovel.

So even by urban-farming standards, Garden Dreams farm has a notable amount of street cred. It also earns a few bucks.

In a good year, Schwartz will sell 4,000 plants at $2.75 a plant. Her costs amount to half that, not including the price of her own labor. Schwartz does much of her business through an e-mail catalog, though she attends a handful of local sales events each year. (The next one will be held at Garden Dreams over Memorial Day weekend.)

The challenge of urban farming "is how all of this can generate income," says Grow Pittsburgh's Manion. Foundations are willing to provide seed capital, she says, but while "The funding community in Pittsburgh is extremely generous, eventually this is something that should be able to hold its own or make a profit."

And Schwartz is a model others should study, Manion says. "Garden Dreams is very small-scale, but [Schwartz] does it because she has a passion for it." In order to succeed, "You have to do some real intensive farming, and find a niche."

Schwartz hopes to expand that niche someday, building an outdoor greenhouse and produce stand. Down the road, she envisions building a woodworking shop, and even a smithy.

It's an oddly medieval vision for a post-industrial Pittsburgh suburb. But Schwartz says a radical rethinking of modern life is badly needed.

"My whole thing is using gardening to get people to understand that they're part of a larger system," she says. "We are consuming our planet without replenishing it, and we will consume it all at some point."

Along with organizers at Mildred's Daughters, Schwartz co-founded Grow Pittsburgh, and now sits on its advisory board. The organization has spawned a pair of "edible schoolyards" in city schools, and offers demonstrations to adults.

Not far from Schwartz's Wilkinsburg plot, Grow Pittsburgh is working on a three-acre parcel in Braddock, where locals are planting tomatoes, zucchini and other crops. The hope is to grow produce for the community, but it's also "a very visible demonstration project," says Manion. "There's this juxtaposition of the plot with the Edgar Thomson [steel] works behind it. And there is so much vacant land down there. If you can green Braddock, you can green anywhere."

Or everywhere, says Schwartz. "On this scale in Wilkinsburg, I can be self-reliant," she says. "I can show a model of food sovereignty" -- taking control of what you eat back from agribusiness, whose industrial-scale practices Schwartz decries. "The people who grow the food supply have control of the world," Schwartz says. But garden by garden, quarter-acre by quarter-acre, people can start taking the world back.

"This is the next revolution, I think."

Information on Grow Pittsburgh can be found at www.growpittsburgh.org, or call 412-473-2542. Mildred's Daughters can be reached at 412-799-0833; Garden Dreams at 412-638-3333