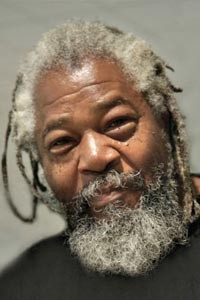

Malik Rahim has been many things. He's been a Black Panther, an armed robber and a social activist. He is currently a Green Party congressional candidate in New Orleans; the election cycle for some Louisiana districts was delayed because of Hurricane Gustav. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Rahim co-founded the Common Ground Collective to provide assistance to low-income residents. This week, the Thomas Merton Center honors Rahim at its annual award dinner, on Wed., Nov. 12.

What was your reaction to Barack Obama's victory?

None, other than to say that history was made. And now it's: How we can really come up with a plan to clean our environment, and then second, do something to save our economy without just giving bailouts to the rich?

Are you upset that New Orleans wasn't mentioned during the debates?

I don't fault [Obama]. I fault our city's administration for not really pushing that we are still really in dire need of assistance. ... The Saints are winning and Mardi Gras was a success, then hey, you're going to have a lack of enthusiasm from any politician. ... It's a city that's based upon tourism, and they believe that telling the truth would be bad for tourists. ... [But people need] to see our school system and the deplorable situation that they're in. To see the health-care agencies, and how in dire need the city is for hospital beds. ... If you look at the lack of opportunity in the midst of a construction boom. ... The tough questions that need to be asked aren't asked.

We can't talk about just building levy walls. We've got to talk about, how can we restore our wetlands? ... We've got to talk about some alternatives for when we have to evacuate. ... We need to constantly teach and train the residents of New Orleans about disaster-preparedness. We can't go on living in New Orleans as if we're living in Arizona.

What needs to change in the reconstruction of New Orleans?

We have to move into a clear direction of hope: How can we assure people that, hey, you can come back. You will be able to rebuild. That we're not just concerned about the French Quarter or the Superdome. That every citizen in this city is important. Once we start doing this, then we will get the people's involvement. ... Right now, if we had just the resources that we are spending on incarcerating non-violent offenders, the Ninth Ward would be rebuilt.

Do you consider yourself a radical?

Yes, indeed, I consider myself a radical. ... It pushes those who are not about peace and justice away, but for those who truly have made a stand for environmental peace and justice, I believe they gravitate towards the ideas that I have shown. ... It's not like something that I'm saying is wrong. People have [come] and seen this.

You say the Common Ground Collective has organized thousands of volunteers in New Orleans. What's so radical about people flocking to save a city in need?

Because of the fact that it has never been done: In the history of America, never have you had 18,000 predominantly whites come into an African-American community in solidarity. Not as exploiters or oppressors. This is the first time this has been done. And they have lived in those communities and have helped to rebuild. ... Yeah, some people might call it radical, but there are people who classify Christ as being radical. Mohammad was a radical. I'm in good company.

What do you think of people calling Obama a radical for associating with Rev. Jeremiah Wright and former Weatherman Bill Ayers?

I believe it would take a small-minded person to tell anyone that has met with those individuals that "You are a radical." ... This is a nation that was made by radicals. It came into existence by radicals. What's the difference between Obama meeting with those individuals or someone meeting with George Washington? Who could be more radical than the founding fathers of this country?

After leaving New Orleans in the 1970s, you were arrested for armed robbery in California. What happened?

That's what it took to save my life and to change the direction I was heading. At that time, just like most young black men, I was full of rage and felt like the movement had abandoned us, and we did some things that we are no longer proud of. ... I didn't come out of prison asking anyone for any hand. But I had a support mechanism, I had a family.

How did your time in prison shape your role as a prison-rights activist?

I know the plight. I know what is needed to turn people around. I know what is needed to do to build a better tomorrow. ... We have to understand, we cannot jail everyone. It's not the idea that people are born criminals. I'm a firm believer that that's folly. I believe in conditions. We have to talk about cause and effect. What causes a person to resort to crime?

From your perspective in New Orleans, what's missing from the current national political dialogue?

How can we transform this nation into the nation that it once was? At one time America was a great nation, and it wasn't great because we were the most powerful or the richest, it was our ability to reach out and help people in need. And I believe we can do it again.