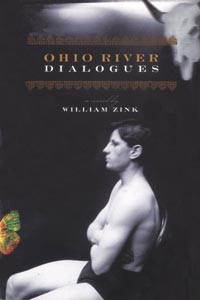

Ohio River Dialogues

By William Zink

Sugarloaf Press, 271 pages, $16

Anyone who's ever talked deep with a small group of friends and thought it might make for art should look into Ohio River Dialogues. William Zink's experimental novel illustrates both the pitfalls and the potential highs of such subject matter.

Ohio River Dialogues tracks 48 hours of a summer-weekend get-together by three brothers and their brother-in-law, at their customary spot along the Muskingum River, a southeastern-Ohio tributary of the Ohio. It's written like a play: With minimal exposition supplied by an omnisicient narrator, it's mostly lines of talk, funny and frank if essentially plotless.

Zink's ambitious goal is to give us the world through the eyes of four men at a particular moment in history. While that moment lies in 2002, halfway between 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq, Dialogues' politics are as personal as they are global. Mostly, it's a book about damaged working-class guys coming to terms with where life has led them, soldiering on in spite of twisted family history and bad marriages.

Simply, Doans, Hector, Emanuel and Gabriel are dealing with disillusion and its fallout; there's much talk about the abortive revolutions of the 1960s, which Doans, the oldest brother here, lived through most fully. But in the early days of the War on Terror, there's a sense of foreboding, of free-thinkers marginalized, America's ideals betrayed.

Emanuel You ever feel like somebody died?

Gabriel Yeah. But you'll get used to it.

Emanuel, not quite 40, is earnest, empathetic, and all the more busted up for it -- especially regarding his carefully nursed grievances against his father, an autocrat who lived most of his life in a wheelchair. While each character gets his moments, from the dreamer Gabriel to spitting-angry liberal Hector, there's a special poignancy to Emanuel's relationship with Doans, a curmudgeonly hipster artist who's buried his idealism deep. When Emanuel says to him, "I thought you were one a the few who knew the score," Doans replies, "What's the point in martyrdom when there ain't nobody there to see you bleed?"

Zink, in his sixth book, ably captures hang-out rhythms, where the talk might be embittered chatter about globalization or crudely amusing talk about the mechanics of sex, and where fishing stories flow into a discussion of Vietnam, where another brother died.

In long passages, Zink's italicized "stage directions" are scarcer than they'd be in an actual play, making the characters difficult to distinguish at first. But one of the book's pleasures is learning the men's distinctive speech patterns -- perhaps especially Doans' mixed-metaphor stream-of-consciousness. Discussing a mysterious episode in the life of their Aunt Pearl, Doans says, "All we got now is some textbook synopsis like some ancient Egyptian sarcophagus frieze relaying the big picture of effect without the pearl string a little pictures tellin' the cause."

Interestingly, it's in his intermittent omniscient passages that Zink showcases both some of his prettiest and some of his least effective writing. There's fine imagery when Hector takes Doans' skull-shaped pot pipe: "Though he gripped a cigarette like a hotdog, he holds the small skull on his fat fingertips like the last egg on earth." But more often the language is carelessly self-indulgent: "Spirits ricochet back and forth against the seamless, timeless walls of thought-imagery." Elsewhere sits a reference to "life's powder cake foibles." What the hell's a "powder cake"? Does Zink mean "powder keg"? Would it make any more sense if he did?

Ultimately, though, what might be trickiest about Ohio River Dialogues is separating its art from its politics. Typically, Zink's guys love their kids but resent their wives, ex-wives and other exes, or at least are baffled by them: women as a foreign country. This highlights a limitation of Zink's self-imposed form: While it's simple enough to supply your own context for things like his boys' penny-ante misogyny -- or their attitudes about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict -- any authorial irony would be a lot more easily conveyed if this actually were a play, or even a more conventional novel.

Zink's characters are self-contradictory, arbitrary, generous, prejudiced, sensitive, self-pitying -- complicated, in other words. You end up liking them in spite of it, or more probably because of it. There's no boiling them down to their essences, and maybe that's Zink's point.