Wittgenstein’s admonition “Anything your reader can do for himself, leave to him” is challenged immediately by Lynn Emanuel in the preface to her new book, The Nerve of It: Poems New and Selected.

Emanuel declares that “chronology is predictable” and “arbitrary,” and then explains how she has cut and pasted together a new ordering of her previous four books (and added several recently published poems), creating what she calls a “new book” full of “linkage” and “collisions.” She tells us she did this to “save you this work,” as if any readers might have done this on their own.

Although Wittgenstein would not be happy, I found this approach both intriguing and frustrating. This is not a collection you can read to understand a poet’s evolution and maturation. Instead, it attempts — in the spirit of the critic Harold Bloom’s theory of revisionism — to let the works establish themselves in hand-to-hand combat: precursor poems following later poems. This recalls Walt Whitman, whose “truest contest was with his own earliest text,” says Bloom. Poets like Whitman often revised themselves. Emanuel, however, challenges herself, and the reader, by inverting her own evolution, in effect, asking us to appraise her older works as new ones.

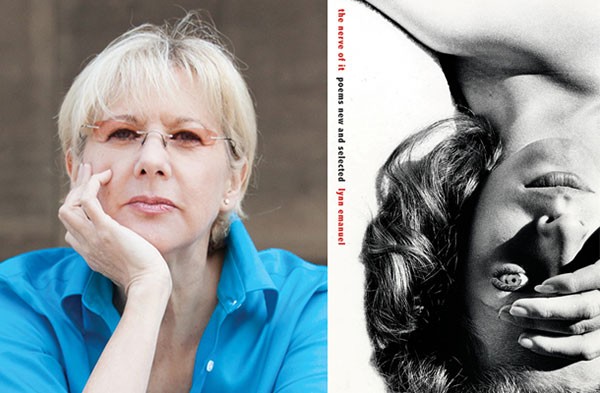

Emanuel, a longtime professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh, is a nationally recognized and much-awarded poet. But much as the form of the book presents a dichotomy, so does the work itself. Emanuel’s poems can be profound and amazing, and just as easily self-reflexive and self-indulgent, sometimes to the point of annoyance.

The best piece in the collection, “Frying Trout While Drunk,” from her first book (1984), is so strong you could teach a master’s-level course with it. The images build on each other subtly, naturally, until you have lost yourself in them and are sitting with the characters around their kitchen table 60 years ago:

When I drink it is always 1953,

Bacon wilting in the pan on Cook Street

And mother, wrist deep in red water,

Laying a trail from the sink

To a glass of gin and back.

The effect bears comparison to the best Raymond Carver short stories, but Emanuel achieves in a mere 29 lines what took Carver many pages to muster.

Emanuel’s favorite trope is self-referencing the poem-as-a-poem. This technique can be interesting when used sparingly but, used constantly — especially in the context of a collection reordered to emphasize such — it becomes numbing. Imagine a film in which the characters constantly stop, look at the camera, and say, “You’re watching a film.” The novelty of this wore off after directors like Godard employed it in the 1960s, and in poetry it fares no better.

Those poems that take self-reflexivity even further usually end up weakened. For example, in “Ars Poetica” (2010), the lines “I have always been a poet / who poured herself into the shrouds / of experience’s tight dresses” come off as forced, and much less effective emotionally. In “Stone Soup” (1992), so many similes are packed on top of each other that the poem becomes claustrophobic. In such examples, the poet would be better served by trying to do less work for her readers, trusting them more and letting the text exhale.

However, Emanuel is often able to achieve brilliance, with works like “On Waking after Dreaming of Raoul” (1992), through sublime simplicity: “those nights she gunned the DeSoto / around Aunt Ada’s bed of asters while you shortened / the laces of my breath.” Other superb pieces include “I tried to flatter myself into extinction” (2010), which is a wonderfully ironic exegesis of her own writing, and “The Dig” (1992), which must be a joy to hear out loud, juxtaposing gorgeous language and rhythm (“faint brickwork of floor spidering the dust”) with a meditation on death.

Deciding whether Emanuel’s anti-historicist ordering of her books is successful is a matter of taste, and I won’t do that work for you. Poems, like any work of art, contain negative space, need to breathe, and certainly react to one another. Sometimes her “linkages and collisions” succeed; sometimes they diminish perspective, as if one were trying to look at paintings in a closet. However, there is enough excellent work in The Nerve of It to merit inclusion in the library of anyone who values original poetry.