After learning that the food court at Monroeville Mall was once a full-sized ice skating rink, it’s easy to see the remnants of it. Still at the center of the mall’s lower level, everything about the space is reminiscent of ice: slick floor-to-ceiling white tile, marble-like pillars, white wall sconces emitting warm light.

“Just where we’re sitting right now, so many amazing things happened,” Bob Mock says. “Olympic skaters skated here, ice show stars skated here, celebrities skated here.”

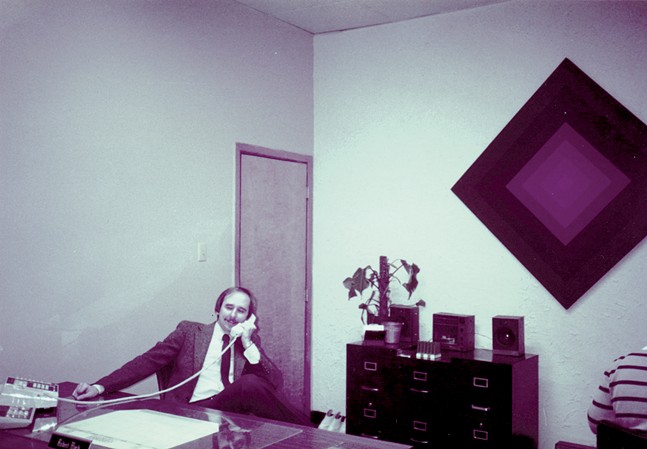

Mock worked as a manager at what was once the Monroeville Mall Ice Palace from its opening in May 1969 until just after its closing in March 1984. He started at 18 — his second job after working in a supermarket — launching a professional skating career in which he’s run his own programs and coached competitive skaters worldwide for more than 50 years. He was once contacted by the FBI about the infamous 1994 Nancy Kerrigan attack (he was at a facility in Portland, Ore. where Tonya Harding trained at the time), and last August, he was inducted into the Professional Skaters Association Coaches Hall of Fame in Florida.

But Mock returns to the former Ice Palace, he says, because people still contact him about it “constantly.” Even after decades of traveling internationally for skating, he still describes the rink as first-rate and “a game changer.”

“Probably one of the finest, if not the finest, ice rink in America,” he tells Pittsburgh City Paper.

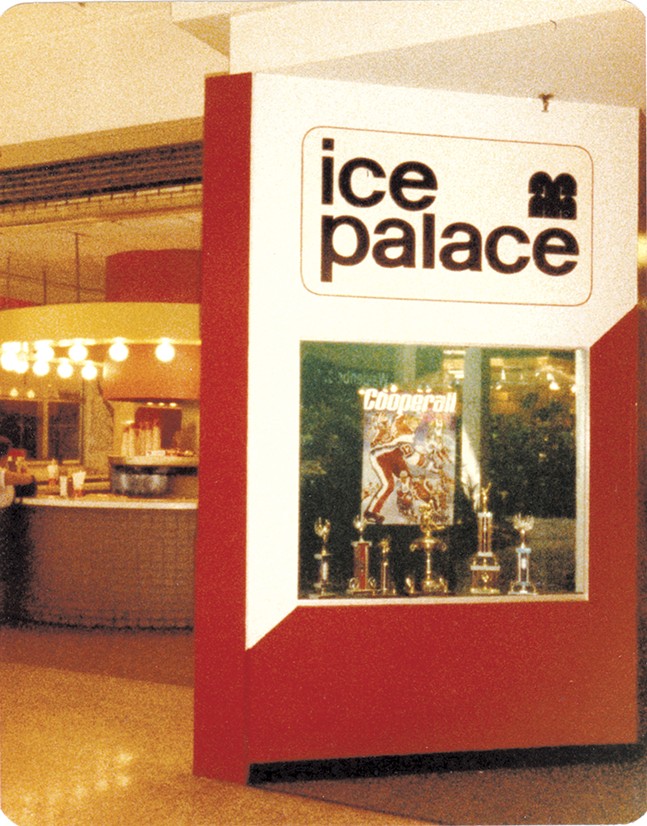

The foremost thing to understand about the Ice Palace, Mock believes, is that the name wasn’t hyperbolic: it was built to be a palace, and there hasn’t been a rink as grand since.

The ice rink opened at the same time as Monroeville Mall — itself a lavish $30 million shopping complex that was part of an explosion of baby boom-fueled retail in the east Pittsburgh suburb. Monroeville Mall was a rejoinder by developer Don-Mark Realty (now Oxford Development Company) to South Hills Village, the largest enclosed mall between New York and Chicago when it opened in 1965. Don-Mark proposed building the largest shopping mall in the country, and designed it 20% larger than South Hills, according to journalist Zandy Dudiak.

Monroeville Mall’s grand opening ceremony on May 13, 1969 touted 125 stores, a two-story “Clock of Nations” with animatronic puppets representing Pittsburgh’s different nationalities, and “a new rink-le in shopping,” according to a promo in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette — an indoor ice skating rink bigger than Rockefeller Center’s.

No expense was spared, Mock recalls. To construct the Ice Palace, architects consulted with George Lipchick — who became the rink’s other manager — an Ice Capades trained skater who’d also taken draftsman classes. The resulting ice surface was supersized — 200 feet long by 90 feet wide — with a state-of-the-art compressor system that both maintained the ice and kept the surrounding air temperature between 65 and 70 degrees.

“The climate control was amazing,” Mock tells City Paper. “You could skate in [the] ice rink and just have a shirt on.” He remembers going to work in a sport coat and tie, a testament, he says, to both the comfortable temperatures — “we’re back to freezing to death again at all the rinks” — and the upscale feel of the Ice Palace.

In addition to the engineering, developers pulled out all the stops on the rink’s aesthetics.

“They tried to make it look like a palace,” Mock says. The rink was enclosed in glass, and everything gleaming white, including what Mock heard were Italian marble pillars purchased for $100,000 apiece. The ice itself was such a pristine sheet that, when Mock first saw it, he inspected to see if it, too, was made of marble. Until the day the rink closed, customers would kneel and touch the ice wondering if it was plastic. Painted orange and blue circles decorated the ice, the colorful design extending up the walls, something “very unusual” for the time according to Mock, since it predated standard hockey rink lines.

Adding to the ambiance, a bevy of restaurants including Di Pomodoro and Schrafft's offered views of the ice rink, and diners came to watch skaters — later in the rink’s tenure, these included Olympic figure skaters and Penguins players — while eating dinner.

“Absolutely everything there was the very best of the best,” Mock asserts. “The best rental skates, the best operating machinery. That’s the experience that people [would] have when they walk[ed] in, that they should be treated like royalty.”

Though Don-Mark Realty said the new rink was a gift to the community, it opened during a proliferation of indoor ice rinks, then a novelty, in the 1960s. There was also a sort of feedback loop between the mall and the Ice Palace: shoppers were drawn in to skate and skaters would stay at the mall to do their shopping. A hot dog stand called Pup-A-Go-Go (which outlasted the rink, eventually slotting into the new food court) served snacks at the rink’s entrance, and at one point Mock was told it was the highest-grossing business in the mall.

At first, the Ice Palace attracted families, offering public skating and figure skating with an option to take lessons. Twenty years before the Penguins won their first Stanley Cup, hockey was just gaining widespread popularity locally.

“You couldn’t give a Penguins ticket away,” Mock says. “[Now] you can't believe it, right?” But as local schools started up hockey teams in the 1970s, the rink added ice hockey, expanding its hours such that it was bustling 18 to 20 hours a day.

Kids, teenagers, and adults took to the ice; couples met and got married. Groups of seniors who’d skated at Duquesne Gardens (which hosted Pittsburgh’s first professional hockey game on its own state-of-the-art indoor ice rink before closing in 1956) came in droves to the Ice Palace, and skated to organ music by special request. An annual Christmas show featured Santa Claus — “this building rocked when Santa came,” Mock recalls. Zandy Dudiak writes in her 2009 book Remembering Monroeville that, at its peak, the Ice Palace pulled in 5,000 people each week.

“I always say I had the best job in skating in the entire country,” Mock tells CP. “Worked around the clock, loved it.”

A half mile away was Monroeville’s Holiday House (today’s Holiday Center strip mall), once billed as “the nation’s finest supper club and motel.” From the 1950s to ’80s, the nightclub brought in top acts including Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., Frankie Valli, and Kenny Rogers. Mock remembers making an agreement with the talent that “whenever they wanted to come over and skate, day or night, we would take care of them.” Rather than the royal treatment regulars got, the staff pledged “not treat them like stars … but as good customers. And they loved that,” he says. Actor Eddie Fisher and daughter Carrie Fisher glided around the rink, as did Goldie Hawn.

One time, rock band The Police were in town performing and called asking to skate that night; an assistant manager told them no.

“She thought it was like the [local] police,” Mock says. “It’s like, you idiot! You just turned down Sting and The Police!”

Monroeville Mall is still most associated with George Romero’s 1978 zombie film Dawn of the Dead. Filmed in the mall overnight during winter 1976-77, the movie's production team stashed their equipment at the Ice Palace. Zombies appear there in the movie, fumbling on the ice and entangling themselves in hockey nets. In 1983’s Flashdance, the rink is also where Jennifer Beals’ character watches her friend figure skate (at the Ice Palace’s final skate session, “Flashdance” was the last song played).

Naturally, the rink also saw its share of athletes: Pirates left fielder and Hall of Famer Willie Stargell; Steelers running back Rocky Bleier; and tennis stars Vitas Gerulaitis and Billie Jean King.

Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw — who later met and married Olympic figure skater JoJo Starbuck — stopped by after a Super Bowl win to sign autographs. The rink promoted it, requiring that anyone wanting an autograph wear skates.

“We had [about] 500 pairs of skates,” Mock says. “Every pair was [rented] out. And then people had their own skates.” Bradshaw was so mobbed that staff snuck him in through a fire exit, but once inside, he signed every autograph — “a true gentleman,” Mock believes.

More than anything, Mock says, he felt a sense of magic at the Ice Palace, that you never knew who might come through the door on a given day, that anything could happen. One summer morning, he was at the rink teaching a figure skating class when monkeys escaped from the mall’s pet store. He and his young students, still laced up in their skates, ran out to see a crew of mall security guards pursuing a troop of monkeys.

“Nobody could catch them!” Mock laughs. Tired of the chase, the monkeys climbed up a lava rock waterfall beneath a skylight — part of the mall’s opulent decor — and curled up to sleep in the sun. As the guards approached with the crowd of kids still watching, “the alpha monkey let out some sort of war whoop,” Mock remembers. “And all the monkeys started running towards them, climbing all over them… All these grown men [were] running through the mall scared to death … One of the best days ever.”

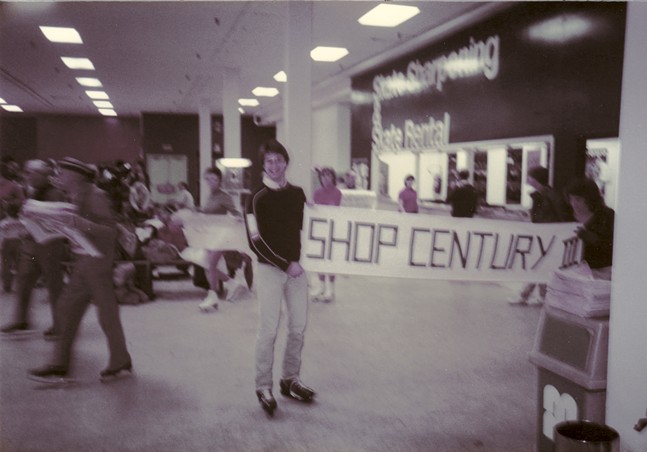

The decision to close the ice rink in 1984 was multifaceted, Mock believes. Following the death of one of the co-owners of Don-Mark Realty, the company divided up property. With Monroeville Mall nearing its 15th anniversary, retail had evolved, and food courts were in vogue. Mock also believes the decline of Pittsburgh’s steel industry decreased business and hastened the Ice Palace’s end. Senior skaters mounted a protest, skating around the rink with signs. Mock even penned a letter appealing to President Ronald Reagan to save the rink.

For years, Mock couldn’t come back to Monroeville Mall, where the food court still stands nearly 40 years later, part of the rink’s original flooring beneath the tile.

“The ghosts are here,” he says. “All the ghosts are in this building. They’re just walking around.”

But at 73, Mock can sit at a table where center ice was and point to the former Zamboni room; the then-cutting-edge ice resurfacer used to emerge from the News Corner Store. His old office, once outfitted with a private bathroom and adorned with 1960s fabric art, is a Crispy’s Fish & Chicken.

“I’m at peace now with this,” he tells CP. “I can sit there and I can say, you know what? … I saw people [pass] their gold medal test here… We had Scott Hamilton here. We had nationals here one year … I can go on. All the top skaters were here. All of them, right here.”

He stays active in skating, following a long, high-flying career. Today, he’s the skating director at Ice & Blades of Western Pennsylvania, and you can still skate with him at Harmarville’s Alpha Ice Complex.

“I’ve done 10 more rinks, but this one was really special,” Mock says. “It could’ve lasted. It would still be operating today.”