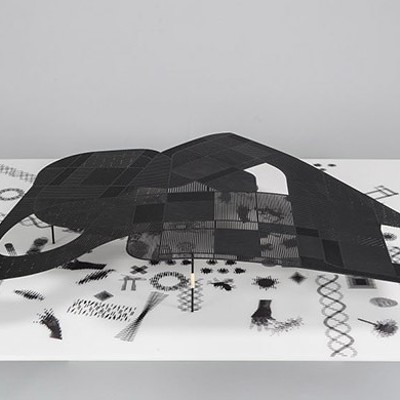

Drawing courtesy of: LaQuatra Bonci Landscape Architects

Burning your bridges is supposed to be a bad thing; you should bury the hatchet instead. Here in Pittsburgh, as if through some terrible collision of bureaucracy and semantics, we've managed to bury a bridge. What had been the Bellefield Bridge, built in 1897 near the Carnegie Library in Oakland, was completely buried by 1913 under dirt that was excavated when the city lowered the "Hump," the formerly elevated area of Grant Street and environs in the Golden Triangle. Now the buried span is the foundation for the Schenley Fountain at the entrance to Schenley Park. Talk about water over the bridge.

Fortunately, rather than face a similarly terrible fate of incavation, another imperiled bridge will be completely rebuilt -- but only because some conscientious architects and planners have worked to reverse its impending earthly demise.

Heth's Run, known occasionally as Haight's Run, begins in Highland Park and runs as a deepening ravine past the entrance to the Pittsburgh Zoo & Aquarium, and down to the Allegheny River. It goes under Butler Street, necessitating an arched bridge that was built in 1914 -- though you'd almost never know.

For decades the city used Heth's Run as a dump for incinerator ash, so the ground level gradually rose up almost to meet the bridge and largely obscure it. Instead of the picturesque 80-foot-deep gully that once flowed beneath the architecturally detailed Heth's Run Bridge, what viewers see looks more like a continuation of the zoo parking lot.

In fact, when PennDOT was recently faced with the need to replace the deteriorating bridge, the agency's first proposal was essentially to fill Heth's Run the rest of the way, create an embankment, and pave that over, effectively creating another buried bridge. Instead, some more creative heads have prevailed.

Pat Hassett, assistant director of the City Planning Department, viewed the project from the perspective of the recently completed Regional Parks Masterplan. The plan "was telling us that we should really look at Heth's Run as an extension of Highland Park down to the river," he explains. Architect David Hance of the Highland Park Community Development Corporation agreed, noting the many important roles the site might play: an entrance to Highland Park (both neighborhood and the park itself) as well as to Morningside and the zoo. Restoring the bridge would also be an opportunity to reassert the tradition of architecturally designed bridges, with which Pittsburgh led the nation before World War I. Hance looked at PennDOT's original proposal and asked, "Can't we do this better?"

With a reassuringly broad-based coalition of community and governmental partners, the answer is yes. While the city had the political influence to intercede with PennDOT and lobby for a change in design, other organizations joined the effort: the zoo, the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, the Morningside Area Community Council. Likewise, increased funding became available from the federal government and the state's Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.

A rendered photomontage shows the considerable improvements planned in the design by LaQuatra Bonci Landscape Architects. A vast swath of asphalt and scrub will become a designed landscape with a soccer field at the south end and a walking trail intermingled with reintroduced water and plantings leading beneath the bridge to the river. The current design proposes a new bridge that closely, but not exactly, echoes the current terribly dilapidated span by T. J. Wilkerson, engineer, and Stanley Roush, architect.

Equally crucial is the planned re-excavation of the site, the only way to reassert the bridge's prominence and make the necessary visual and physical connections through the area. The new digging is no incidental task in what is essentially a brownfield site. Hassett, however, says that state certification will allow the site to be re-graded consistently within safety standards and environmental law. That re-grading will also save what would be the considerable expense of hauling old fill to some other location.

From a utilitarian perspective, digging a bigger hole so you can make a better-looking bridge probably seems absurd, but no more so than burying a bridge because you have plenty of extra dirt. But bridges continue to be powerful metaphors for connection and consensus. If a structure and its landscape can embody those ideas both artistically and politically, then that is an achievement to rival any feat of engineering.