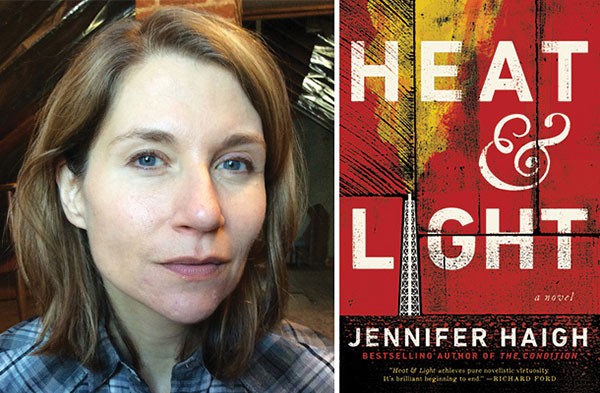

Jennifer Haigh grew up in small-town Cambria County — coal country, though as a teenager in the 1980s she witnessed the region’s economic decline as mining faded. While Haigh now lives near Boston, she frequently returns to Western Pennsylvania in her critically acclaimed fiction, such as the 2005 novel Baker Towers and the 2013 short-story collection News From Heaven.

The advent of hydrofracturing for natural gas — fracking — brought Haigh back again. Her stellar new novel, Heat & Light (Ecco), tracks a large and diverse cast of complex, flawed characters through the first years of fracking in fictional Bakerton. They range from a gas-company leasing agent and a prison guard hoping to cash in on drilling to a lesbian dairy farmer and her partner; an environmental activist; the Texas-based head of a drilling firm; and the prison guard’s wife, who fears fracking’s health impacts. Money gets made; water gets contaminated; and relationships are threatened.

On May 23, Haigh’s book tour hits Pittsburgh. She recently spoke with CP by phone.

Fracking’s divisive. Do readers want to know your “position”?

Yes, and this is a novel that is bound to disappoint everybody who wants that. That’s not what I do. That would make for some terrible, terrible fiction. Whatever personal feelings I have about fracking were constantly changing as I wrote this book. It’s the magic of point of view. As a fiction writer, you inhabit one character at a time, and you see the world through that person’s eyes. … So the sections I wrote from the point of view of Kip the Whip, the CEO of the gas company, I’m looking at the world through his eyes, and I’m suspending any other judgments and contradictory views I might have. … And that happened again and again because there are so many points of view in this novel.

How do you approach your research?

I think of writing novels as an exercise in empathy. It’s deep empathy. So what I’m trying to get at is, “What does it feel like to be this person?” … When I talk to a guy who works on a drill rig, I’m not looking for verifiable facts so much as, “How do you feel at the end of the day? Does your back hurt?”

Yet, you do include technical details.

If you work in that industry, it’s all about the equipment. The guys have a lot to say about the equipment, a lot of opinions about the equipment, and that’s endlessly interesting to me. I love writing about machines. … There’s a section that deals with [1979’s] Three Mile Island [nuclear] accident, and I got really absorbed with learning everything I could learn about how that reactor worked.

Why all the TMI stuff?

The fact is, Pennsylvania has always been an energy state. This goes back to the 1850s, the first oil well being drilled in Venango County. … This has everything to do with how people in Pennsylvania have responded to the fracking opportunity or debacle, depending on which side you’re on. … [Three Mile Island is] really another example of Pennsylvania being on the forefront of energy, and reaping the benefits and also being affected by the consequences.

So Pennsylvania’s an outlier?

People in Boston — to a one, every person I’ve talked to here — thinks fracking is a terrible idea. It’s an environmental disaster waiting to happen; why would any community ever consent to that? When I go back home, people see it in black-and-white terms also, but they look at it from the other side: “Well, if I have this piece of land, and I’m not doing anything with it, and someone’s going to pay me a lot of money, and I get to keep the land, why would I not do it?”

What about the novel’s motif of addiction?

That was a complete surprise to me. It developed as I wrote the story. It’s true that a lot of these towns that have fallen on hard times have drug problems. They also have a thriving bar culture from way back. … Recently the methamphetamine thing and the opiate thing has hit rural America very hard and this region in particular very hard, so that is a piece of the story.

As I wrote, I thought a lot about [characters from] the Devlin family. Dick Devlin owns the commercial hotel, the tavern. He’s in the addictions business, you could say — he’s a coal-miner who lost his job, went into the addictions business, bought a tavern. His older son is a corrections officer at a prison full of drug offenders. His younger son is a recovering heroin addict who’s a counselor at a methadone clinic. They’re all now in the addictions business. A generation ago, they would have been a mining family.