In almost every way, the house is an ordinary, two-story Pittsburgh dwelling. Perched on a darkened side-street that sees little traffic, it could be any working-class neighborhood's home to 2.5 kids. Could be, that is, if it weren't for its eyes. Roving eyes fill the second-floor windows, watching the street like those of a guard dog. But as they dart back and forth, over a period of minutes, the eyes drift out of synch: The left eye begins arcing to its right just as its brother reaches the left side of its path.

Meanwhile, deep in the bowels of Carnegie Mellon University's Doherty Hall, the eyes themselves are being watched. Osman Khan's computer is projecting a film of this house onto the wall of his darkened classroom. Michael Kontopoulos, a senior finishing his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree this year, created and installed the projection, a video of his own eyes, filmed and projected into the windows of his East End home. He created the project in response to a friend's anxiety over a possible stalker, but it fit perfectly into an assignment in Khan's class on Interactive/Reactive Environments. Students had to create a piece using projections. It's just one of many "new media" tools they'll learn to use -- video, projections, electronic sensors.

New media is a different breed of art, one that uses digital technology the way some artists might use a paintbrush. But CMU has become well known in the field: From new-media superstar Simon Penny's tenure in the 1990s, to a more recent stay by pioneering robotics artist Frank Garvey, CMU has always had one or two new-media "rock stars" on campus.

"There are a lot more [robotics artists] in Pittsburgh than there are in a lot of other places, because of CMU as well as the culture of the town," says Ian Ingram, an emerging artist in the field. "It's somehow just in the blood of the city. ... [T]here's a grittiness to robots -- they exist in slightly greasier zone. Maybe that's a romanticized view of Pittsburgh, but somehow it seems to me that's right for here."

While CMU continues to attract internationally known artists such as Khan and promising students such as Kontopoulos, local exposure outside of the university's campus has traditionally been limited. But a new generation of artists isn't just putting Pittsburgh on the map. They're making sure people here know about it as well -- on- and off-campus. Philosophically, meanwhile, they're more willing to confront the very technology that makes their work possible.

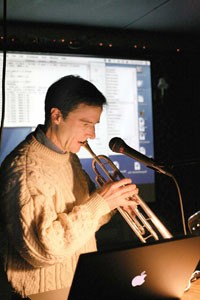

Despite the icy weather outside, Lawrenceville hipster haven Brillobox is packed on a recent Thursday night in January. But what commands the attention of the standing-room-only crowd is not some indie-rock band's hirsute posturing: It's mild-mannered CMU professor and computer-music pioneer Roger Dannenberg.

Trumpet in hand, Dannenberg shows how his new foot controller allows him to trigger accompaniment for his instrument in a live-band situation -- pre-recorded samples whose tempo and groove change with the flow of a live performance.

This is "Dorkbot," a monthly gathering for those working on the fringes of technology, walking the blurred line between new-media arts and tech-product development.

Dorkbot's purpose was to provide a space for artists and technologists whose work, by virtue of its very cutting-edge nature, didn't fit into established genres. This somewhat amorphous mission is aptly summarized in Dorkbot's one-line mission statement: "People doing strange things with electricity."

"In the academic publishing and conference world, the only stuff that gets on [a conference] is stuff that's extending the state of the art -- that people didn't know how to do before," says Dannenberg. "What I see at Dorkbot is people using stuff that exists, but they're very creative about it, and that doesn't really have a forum."

Begun in 2000 in New York City by Columbia University-based artist Doug Repetto, the Dorkbot concept soon extended to loosely affiliated franchises in tech- and art-savvy cities such as London and Tokyo. But it wasn't until last year that Dorkbot took hold in Pittsburgh -- despite what would seem like a ripe atmosphere amongst the CMU technorati and Pittsburgh's other research hubs.

"It was after I saw that there was a Dorkbot in Minsk that I thought, 'What is going on? Why don't we have one in Pittsburgh?'" says local Dorkbot co-founder, and CMU art professor, Golan Levin.

Levin wrote to Repetto with the intent of starting a local chapter and discovered he wasn't the only one interested: Repetto had also been contacted by a CMU design student, Jet Townsend, and freelance computer wiz Drew Celley. The three met up, and in April of 2006, held the first meeting of Dorkbot Pittsburgh.

Since then, attendance at Dorkbot has been sizable, typically drawing crowds of between 50 to 75 or more people. And the event's off-campus location is central to its goals.

"When it came time to plan the first meeting, [I thought] 'Well, I can get a lecture room with a projector, and a bowl of pretzels,'" says Levin. "But if we did that, it'd be only CMU students showing up. The rest of Pittsburgh would say, 'Oh, it's a CMU thing.' We don't want this to be a CMU thing. We're working hard to get a non-CMU audience."

Much of the work exhibited at Dorkbot, after all, explores multiple artistic and technological disciplines, as well as elements of the culture we all have in common -- like the creeping influence of technology on culture. The results can be both funny and somewhat chilling.

Take the work of Osman Khan, a visiting professor at CMU's College of Fine Arts who showed work at November's Dorkbot.

Khan demonstrated several projects, which are collected as a series titled Weapons of Mass Consumption, and which use a credit-card swipe machine to display information about those who interact with the installation. "Net Worth," for example, automatically scans the cardholder's name through an Internet search engine; based on the number of hits the name receives, "Net Worth" ranks the user's name in importance as compared to famous and infamous celebrities -- all displayed on a large screen for everyone to see.

"It's amazing how competitive people get," says Khan. "I've had professors [participate], and then actually go and do work on the Internet so that next time, they'd be ranked higher."

Khan's work examines the tradeoffs we agree to in the name of technology. What values do we alter? What privacies will we relinquish? And what's the value of Internet celebrity anyway? Amongst the top-level "Net Worth" names, after all, is a certain Osama bin Laden.

"I suppose I'm complicit in that [commercial] society" by making pieces that play on it, says Khan. But, he adds, "There's a narrative in all these kinds of products, and I'm just trying to twist that narrative.

"[I]t's almost like the way Warhol was, appropriating media and celebrity -- he was still always the outsider."

For all their technological sophistication, Dorkbot artists remain outsiders too. While the Dorkbot team has found it easy to attract audiences, it's been tougher to find presenters.

Khan's own connections to Pittsburgh are somewhat wayward: He first lived here in the 1990s, working in the Internet bubble as creative director for a tech start-up. He left to complete an MFA from UCLA, and then began his second spell in Pittsburgh last year.

It's not that Pittsburgh lacks for people doing relevant work, Jet Townsend argues. It's that those doing the work don't always know they'd fit in.

"People have this idea that an art salon is for 'capital-A' artists -- people with art careers," says Townsend. Another November presenter, Kevin C. Smith, "is a musician, doing circuit-bending basically in his room. ... That same night we had Garth Zeglin, a roboticist who's getting into the art side of things. So here're two people deeply immersed in their fields, but you stop and think, 'Which one's going to present at an art salon?'"

Especially when technology and the arts often don't see eye to eye.

When Ian Ingram talks of gnome-hunting along the Scottish border, or creating a device to lure the elusive giant squid, he does so with such unpretentious enthusiasm that it takes a moment to register what he's saying. The first impulse is to respond matter-of-factly: "OK, sure, so you're hunting the giant squid, like people do."

An MFA student at CMU, Ingram's life reads like a Wes Anderson film script. An Army brat raised everywhere from Copenhagen to New Hampshire, Ingram continued his nomadic lifestyle as an adult, traveling much of the year while working as a telecommuting animator and consultant. ("My clients were in Italy," he says. "They didn't know or care that I was sleeping in my van in Texas.") Ingram wound up at MIT, studying engineering and ocean acoustics while working on technologies with a group of friends -- Deep For Cheap -- interested in finding that damn giant squid.

"I saw the giant squid -- especially before they actually found it -- as a metaphor for the mysteries of the ocean," says Ingram. "There's still stuff out there, mythical things -- things people know exist, but they can't find them. I became infatuated with things under the ocean."

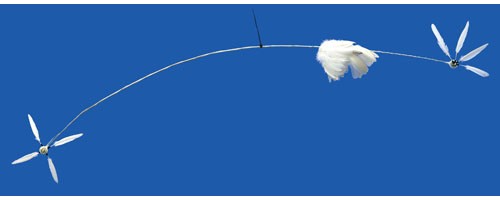

In fact, while Deep For Cheap's goals were sincere, some of their projects were more about concepts than actual squid-baiting. The Giant Squid Call, for example, used artificial lures designed to simulate the squid's color-changing skin, in hopes of sending a message the squid would respond to. "We'd make these devices," says Ingram, "stylized, comical, Goldbergian on purpose. And we'd take them to the ocean to look for the giant squid. Kids would find us and ask what we were doing, and we'd explain to them about the squid, and [our work]."

Unfortunately, while kids might love it, MIT's engineering professors were less impressed. Robots that simulate the movements of a real-life creature are an important part of robotics research. But robots that simulate movements in intricate, aesthetic patterns, or that relay a sense of mystery and magic -- not so much.

"I was interested, like a lot of people working in robotics, in making [robots that dance], but I wanted to do it underwater, making these creatures that could swim with real fish," Ingram recalls. "I wanted to take that stuff and extend it into elaborate, Busby Berkeley kind of underwater ballets. My advisor didn't think this was a particularly productive thing to do."

What changed his advisor's mind wasn't the project's pure beauty: Ingram eventually repackaged his dancing fish as a platform for studying multiple-vehicle systems. Making that compromise helped teach Ingram that many of his life's ambitions -- like myth and storytelling -- didn't fit into engineering's worldview.

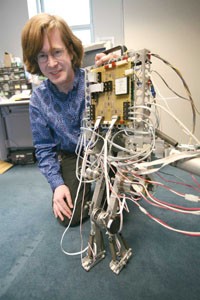

So Ingram has synthesized those interests in a series of robotic artworks -- or, as he and other so-called "robotics" artists prefer to call them, mechatronic sculptures. "Mechatronic" denotes the integration of mechanical and electronic engineering, but without the baggage of the "r" word, which suggests both pop-culture images of "Robbie the Robot" and the more utilitarian robot that engineers prefer.

Ingram's pieces are abstractions of the form and behavior of real-life animals. They're meant to thrive in natural environments, while also suggesting Ingram's intricately layered mythologies of forgotten creatures and undiscovered species.

Take "Stuttering Magpie," a bird-like sculpture that uses a series of movements of its "beak" and "tail" to cast shadow-puppet images on the gallery wall. These forms point the viewer in a direction, allowing the magpie to pass information along in its own language. It's like a bee's dance directing other bees to pollen -- another of Ingram's obsessions. "When [humans] figured that out and made a bee drone" that waggled to real-live bees, he says, "I think that's the first time we spoke to another species in their language."

Ultimately, sculptures are clues to what could be seen as Ingram's real exhibit. Ingram hopes to lead viewers on a trek outside the gallery, to a natural environment such as Schenley Park, where his mechatronic "creatures" can thrive "naturally" for extended periods of time.

To further his own quest, Ingram has joined with fellow roboticist-turned-artist Garth Zeglin to form "Rossum's" -- a local group of mechatronic artists named for the 1921 Czech play, Rossum's Universal Robots (which gave the world the word "robot"). The group's first show, Mechanosphere, opens Friday at the Three Rivers Arts Festival gallery.

While Ingram was struggling with how to fit his artistic interests into an engineering paradigm, Zeglin was struggling with the opposite problem: fitting his engineering interests into an artistic paradigm. Zeglin, who holds a Ph.D. in robotics engineering from the CMU Robotics Institute, now works as a CMU robotics project scientist. But he had a burgeoning interest in the art world, for which he was consulting on technology more and more frequently.

"I was preoccupied with creating an identity other than as an engineer," Zeglin says. "Because I do technology professionally, I felt like I might be tarred with the brush of it if I just did technology-art. ... I liked using technology as a tool, but I wasn't all that keen on trying to comment on technology itself as a subject."

Unlike many roboticists, Zeglin sees research and art as similar processes. Each one involves formulating an abstract question, and then creating some kind of concrete model to answer it. "The big difference is in the nature of the question," says Zeglin. "In art, it can be extremely personal, self-defined, idiosyncratic."

As part of his effort to find peace with his inner technologist, Zeglin created "Albatross" for Mechanosphere. "Albatross" is an ongoing effort: Zeglin began working on it more than five years ago. The work features fabric hung from lightweight wires, and uses simple motors to float and dance in space, as if on an invisible wind.

"I was trying to focus on the machine as being a lens through which you view this behavior," explains Zeglin.

Ingram calls his approach to art "Lamettrian Geppettoism," after the French philosopher Julien Offrey La Mettrie, and the Italian woodcarver and life-imbuer. (Ingram's artist statement credits La Mettrie for "asserting that both the body and mind were machines"; Geppetto, meanwhile, acted with the "beneficence of a Fairy Godmother," by imbuing Pinocchio with life. "Lamettrian Geppettoists have freed up Fairy Godmothers to pursue other activities," Ingram writes.)

Pure roboticists are disinclined to the kind of approximation of life that Ingram practices. It's a response that Zeglin says is still strongly ingrained in him: Any claim -- whether practical or purely artistic -- to create artificial life or artificial intelligence is "a dangerous business," he says.

People often respond to robots as if the machinery's actions reflect some emotional or psychological state, Zeglin adds. "[They'll] say, 'It wants to go out the door,' when, of course, I'd say it doesn't have anything that could remotely be called intention or thought. In the interest of observational clarity, I'm always very unwilling to ascribe any intention to a machine."

Zeglin's grappling with this fallacy led to his other contribution to Mechanosphere: a bird-like mechatronic installation called "Fledgling." By flitting up and down the vertical wire on which it "lives," the fledgling reacts to the presence of gallery visitors: first appearing to hide from newcomers, and then gradually becoming more accustomed to them. "Fledgling," in other words, seems to react emotionally to its viewers. And while no one would mistake it for a real bird, there's no mistaking what it's supposed to look like, either. It may not be a full-fledged simulacrum of a bird, but it has clearly broken out of the shell of diodes and wiring that house most robots.

Most robotics researchers prefer their machinery to be as stripped-down and functional as possible. "Some people criticize the idea of hiding how [a robot] works, because they feel that's illusory," says Ingram. "But in a way, it's illusory no matter what, because if you're using integrated circuits, it's just a little black box -- even I don't really know what's going on in there!" Ingram also says that making technology the focal point of a work actually limits the technology: "[I]f you need to show how something works every time, you're sticking to a rather small range of aesthetics. The kinds of technology that we work in can be used in so many ways that don't have anything to do with the technology [itself]."

Taking mechatronic artwork past the novelty of the technology itself could help propel these creations out of the lab and into the mainstream. But when you learn your craft in the engineering sphere, it's hard to get accustomed to newfound artistic freedom. Zeglin says he's had to "unlearn" some of the habits he was taught -- which is why he works with Rossum's in the first place.

"I've kind of languished off on my own, and that's been a hindrance to my progress," says Zeglin. Watching Ingram explore the aesthetic potential of robotics, however, "helped me give myself permission to do it. [Normally,] I'd shy away from 'artificial life,' and here's something that's pretty gleefully trying to be artificial life."

As for the debate between robots-for-robotics' sake and robots-for-art's-sake, Zeglin says, "It's not a resolved question, which is why I'm doing the piece." His "Fledgling," he says, is "what's called a believable agent -- where you say, 'It doesn't matter if something is intelligent or not. All that matters is how a person responds to it.'"

Playing off people's response to technology is at the heart of Golan Levin's career -- and it's been a successful career at that.

Levin is one of the most important new-media technology artists working today: This year alone, his work will show at important new-media festivals and galleries in Denmark, Belgium, England, and at New York City's Bitforms, the gallery that represents him. His pieces often stress interaction between digital technologies and human gestures, finding new ways to interpret movements, sounds and expressions with technology. For example, "Messa di Voce" visually interprets the sounds of improvisational vocalists, projecting them as shapes and colors streaming across a screen. "The Manual Input Sessions," meanwhile, reverses the process, transforming hand gestures and scribbling on an overhead projector into complex electronic graphics and sounds.

Levin relocated to CMU from New York City in 2004, and his recent work has been directly influenced by the move. Using technologies being created within CMU's computer-science department, Levin's work points out some of the unique artistic possibilities -- and problems -- of working at a large, tech-based institution such as Carnegie Mellon.

"I've been talking to people [in computer science] to beg, borrow and steal code to do some fancy things that I'd not be smart enough to write myself," says Levin. "It's stuff like face recognition, eye-tracking, gaze-tracking -- other kinds of very intelligent ways that computers can make assertions about things they're seeing through video cameras."

Of course, that technology has obvious possibilities for surveillance -- the purpose for which much of it was designed. And although Levin says art has the potential to "turn swords to plowshares," he admits that many researchers he collaborates with are "not thinking about [art] at all. They're literally funded by the government to do quasi-military research, and that's fine for them."

"I'm interested in the idea of technology being primarily motivated by art making, rather than commerce and the military," says Ingram. Part of what inspired the Rossum's group, he says, was the hope that technology could be redirected toward aesthetic, rather than military or security, ends. Rossum's had a "political agenda of making our stuff, making it kind of great, and then having it change how people thought about technology," he says.

"The whole point of academic life is that results are shared," says Zeglin. "Anything I've done [can be used by] someone else to turn into a weapon. And the converse is also true: Anything that they build I can appropriate and turn into art."

At any rate, it's an inescapable fact that the funding and impetus for technological innovation often stems from defense interests. And as Roger Dannenberg says, CMU has a culture "in which there's no stigma attached to working across disciplines. Instead of, 'Oh, he's that guy that's working with somebody across campus,' like there's something wrong with that, here it's, 'Oh, cool, you're [a musician] working with someone in design!' The Robotics Institute is a good example. It was formed as a collaboration between computer science, electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, and I'm probably leaving some out."

Levin believes that this cross-disciplinary attitude could help Pittsburgh dominate the field of robotic art.

While many other places -- like the San Francisco Bay Area, or Cambridge with MIT's Media Lab -- have reputations for new-media work, Pittsburgh could be the place where mechatronic art integrates itself into the cultural mainstream.

"Robotic art could be huge here," says Levin. "Because of the unusual strength of robotics that CMU has, if we had three or five faculty in [specifically] robotic arts, we would literally just kill the field; we'd command it."

Dorkbot, featuring guests Jason Simmons of Gradient Labs, and composer/choreographer Grisha Coleman of Hot Mouth, is at 7 p.m. Fri., Feb. 23 at Brillobox, 4101 Penn Ave., Lawrenceville. 412-621-4900 or www.dorkbot.org/dorkbotpgh/

Rossum's show Mechanosphere, featuring work by Stuart Anderson, Takehito Etani, Doug Fritz, Amisha Gadani, Joseph Hays, Ian Ingram, Michael Kontopoulos, Shaun Slifer, Gregory Witt, and Garth Zeglin, opens with a reception 5:30-8 p.m. Fri., Feb. 23 at the Three Rivers Arts Festival Gallery, 937 Liberty Ave., Downtown. 412-281-8723 or www.artsfestival.net