This is an edited excerpt from Animal You’ll Surely Become, a work of poetry and nonfiction scheduled for release by Tolsun Books in October.

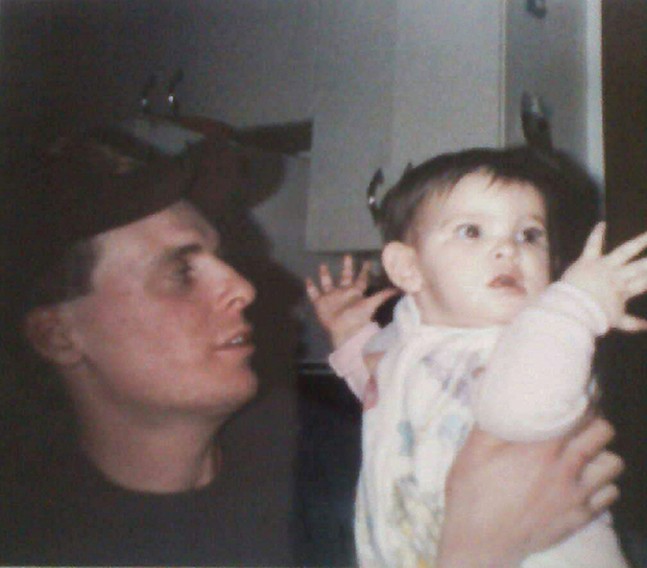

__I met my father for the first time when I was 25. He’d been in rehab over a year. He asked to come see me in Pittsburgh. For the first time in his or my life he seemed timid, quiet even. He told me that a lot of things had come out in rehab, things to do with the Catholic Church.

Dad picked me up, and we went to the Manor Theatre in Squirrel Hill. He walked with his hands shoved in his pockets. He shuffled where he stood, kicked at nothing. We bought the biggest tub of popcorn they offered, a pack of Twizzlers, and two Cokes. The movie was Spotlight.

My father sat with his elbows on his knees, tears streaming down his face. He’d lean over and say “that's exactly right” when characters described abuse or tactics priests used to groom their victims. I sat frozen beside him. Dad started to shake his leg and tap his foot. He got so excited when Mark Ruffalo, playing Michael Rezendes, confronted his editor, pleading to publish the investigation sooner. Dad jumped out of his chair and cheered.

After the movie let out, I rushed to the bathroom. My father and I, two repressed and orbiting planets, didn’t know what to say. We walked in silence before I cut into the women’s restroom. I wasn’t sure what I had just learned. In the bathroom stall, I breathed.

Dad waited for me outside the bathroom. We walked out of the theater and into the street, a clear energy in the air. Neither of us spoke, as if we knew we were about to cross a threshold. There would be no going back once one of us said it.

In the street, outside the Manor, my father told me he was raped.

Me and Dad ducked into a nearby bar on Forbes. I asked if he was going to be OK. He said being around other drinkers didn’t bother him anymore. We ordered coffee. He told me the priest’s name.

There were other boys. A lot of them. My dad spoke evenly. He sat up straight. He seemed lighter. He seemed, for the first time, at ease. The only image he gave me was this: his boyhood clothes in a lump on the floor and him, naked, picking them up afterwards while the priest watched.

When he was 11, my father told his mother about his abuse. She didn’t believe him. A devout Catholic, she told him to keep it to himself. She signed him up for spiritual counseling with the priest. She pushed him into the fire.

Another reporter says in Spotlight, “If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a village to abuse one.” Dad kept repeating that line all night.

In the bar, over coffee, Dad and I talked for the first time in our lives. We talked about how the universe seemed to be clicking into place: the movie, the booth, my father’s sobriety. We were exactly where we needed to be in this moment. Sober. In a smoky bar. Listening. Saying, yes, this happened and I am sorry. It was intoxicating. Two months later, my father would relapse.

After Dad’s relapse, the priest haunted him.

Well, maybe he always had, but now Dad would tell me about it. He’d call over and over again and tell me what the voice was saying to him in the dark. He would text me 20 to 50 times in a row. I would be out with friends with a madman in my pocket. I would be working, meeting professionals, going to the movies, and his words buzzed in my purse. No one knew the suffering I was receiving. The sentences of pain. My father, drunk with trauma. Each a buzz. Each a reminder that so many of us had failed him.

That he had failed himself and he was dying because of it.

Eventually, my father would file a lawsuit against the Catholic Church. The other man who came forward with him is a heroin addict. His trauma also came out in rehab, but he couldn’t remember the priest’s name. He called Dad. Dad remembered.

Dad and this man contacted the other men who were once boys with heaps of clothes on the floor, who were once lookouts, too. They said they had families. They were men now. They couldn’t face it again. They never told their wives and families. Some said they didn’t know anything about any priest. They all shut their doors and continued their lives in silence.

My father has since been diagnosed with PTSD and complex trauma. And alcoholism. I’ve been diagnosed with codependency.

__

Follow author Brittany Hailer on Twitter @BrittanyHailer.