What's the difference between homage and simply ripping someone off? Just the blatancy with which you do it?

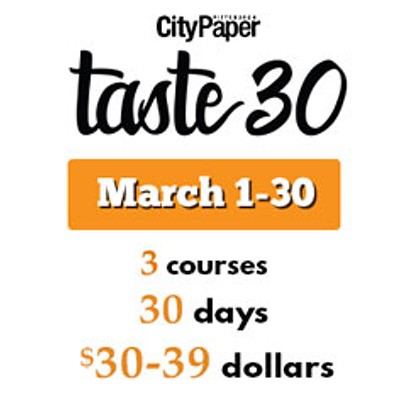

Beginning with this issue, City Paper adds a new feature: a weekly installment of serialized fiction written by local authors.

We begin with a month's worth of "lost episodes" from Honeymooners: A Cautionary Tale. Previously unpublished, the chapters extend author Chuck Kinder's fictionalized account of his friendship with famed short-story writer Raymond Carver during the 1960s. The first chapter begins on the facing page: Appropriately enough, it's about two men who set out in search of a story ... only to become the story they were seeking.

Something similar happened to Kinder, a West Virginia native and University of Pittsburgh professor. He labored over Honeymooners for decades, and his struggles were so epic that they became the subject of a book themselves: Wonder Boys, by Michael Chabon, Kinder's former student.

Why launch a feature with outtakes from a book published in 2002? Because we hope to celebrate Pittsburgh's literary community, in all its splendor and occasional squalor ... and Honeymooners depicts, in humorous and wrenching detail, how splendor and squalor translate from our lives to the page. And while the book is a few years old, it speaks to questions that are convulsing the literary world today.

Sometimes, the line between fiction and nonfiction is extraordinarily thin. You can say, for example, that Honeymooners is a fictionalized account of real events. But as the book makes clear, real events are sometimes driven by the dictates of fiction. As Kinder puts it, "an Italian journalist once asked me if I thought Jim Stark" -- the stand-in for Kinder in the book -- "was an alter ego for me. I said, 'No. I'm an alter ego for Jim Stark.'"

In fact, I have my own story to tell about Kinder, and some of the concerns lying beneath his work. The tale begins where a lot of Chuck Kinder stories do: in a bar.

A couple months back, Kinder and I got together over beers to talk about launching this feature. In a characteristic act of generosity, he gave me copies of two books: Honeymooners itself and Last Mountain Dancer -- a "meta-memoir," as Kinder calls it, about the weirdness and wonder of his home state of West Virginia. And as it turned out, we share an interest in the West Virginia Mine War, an obscure chapter of 1920s history in which an insurrection by coal miners was put down by the U.S. military. In Dancer, Kinder earmarked a chapter about Sid Hatfield, a real-life lawman who took the miners' side and was thus gunned down on the steps of a courthouse.

A few nights later I read the chapter, in which Kinder recounts visiting the barbershop where Sid had his final haircut. Kinder sits in the barber chair, imagining Sid's last hours:

The old barber positioned Sid a last time and then he brought his head down next to Sid's. They looked into the mirror together, the old barber's hands still framing Sid's head. ... Maybe Sid and the old barber simply looked into Sid's eyes together, as though some hidden inkling of the future might be reflected there. But if the old barber saw something, he didn't offer comment. ... The old barber ran his fingers through Sid's hair tenderly, as Jessie might have done it, like a lover.

... It's pretty to think that Sid had made up his mind about what he was going to do and why he was going to do it while sitting in the old barber's chair. Sid's choice had had something to do with that sense of calm he had felt when he closed his eyes and let [the barber's] fingers move through his hair, the sweetness of those fingers, his hair already starting to grow again.

That is pretty, I thought. It sounds almost Raymond Carveresque.

And then I thought: It doesn't sound Raymond Carveresque. It sounds like Raymond Carver.

Sure enough, a few minutes later, I was reading the following from Carver's short story, "The Calm":

The barber turned me in the chair to face the mirror, it reads. He put a hand to either side of my head. He positioned me a last time, and then he brought his head down next to mine.

We looked into the mirror together, his hands still framing my head.

I was looking at myself, and he was looking at me too. But if the barber saw something, he didn't offer comment.

He ran his fingers through my hair. He did it slowly, as if thinking about something else. He ran his fingers through my hair. He did it tenderly, as a lover would. ...

I had made up my mind to go. I was thinking today about the calm I felt when I close my eyes and let the barber's fingers move through my hair, the sweetness of those fingers, the hair already starting to grow.

"The Calm" was published in 1980 -- 24 years before Kinder's book.

At first blush, this looked like an act of straight-up plagiarism -- the kind of literary crime that has made national headlines recently. Had I caught a pre-eminent Pittsburgh writer in a cardinal sin?

Then again, in Kinder's story the barber's name is Ray: If Kinder were stealing material, would he name a character after his victim? Was this a homage, then? If so, what's the difference between homage and simply ripping someone off? Just the blatancy with which you do it?

Moreover, Carver's own originality has been questioned: One of his wives has claimed much of the credit for his work, and his famed story "Cathedral" resembles a piece by D.H. Lawrence. If Kinder stole material, who did he take it from? Is it stealing if the victim is a thief?

Such ethical questions seem up for grabs like never before. The most famous example is James Frey's A Million Little Pieces, a purported "memoir" about drug abuse whose exaggerations got the author dressed down by Oprah, no less. But there have been enough other such incidents that in this year's 412 Creative Nonfiction festival, a key theme is "Ethics in Writing."

"Is it fair or ethical to reveal intimate details about friends and family?" the festival's press materials ask. "How can writers -- and readers -- navigate the gray areas between fact and fiction, accuracy and embellishment?"

Here's how Chuck Kinder answers those questions, respectively: "Hell, yes"; and "What's the difference?"

Actually, those aren't really Chuck Kinder's responses. In the spirit of the times, I just made them up. But they seem consistent with his work. After all, Mountain Dancer begins with the disclaimer that while some names have been changed, "Everything else is as literally true as the Bible." (A double-edged assertion if ever there was one.) And as the Honeymooners chapter presented in this week's issue asks, "Who would wish to clutter ... a perfectly good story with dubious facts?"

Maybe not as many people as you think. To hear the critical uproar over Frey's book, you'd almost never know that these questions date back decades, to the rise of New Journalism if not before.

When Tom Wolfe pioneered New Journalism in the 1960s, some worried that his approach -- writing about real-world events in a novelistic narrative --was setting a dangerous precedent.

"These blurrings" between fact and fiction, fretted journalist and author John Hersey in a 1980 essay, "help soften the way for, or confirm the reasonableness of, public lying." The decade that followed may have proved Hersey right. President Ronald Reagan's press secretary was once challenged over the accuracy of some presidential anecdotes. The secretary's reply: "If you tell the same story five times, it's true."

Kinder, of course, is simply telling stories, rather than setting policy for the most powerful nation on earth. But he's similarly blasé when it comes to questions of authenticity. When I confronted him with the excerpt from "The Calm," his response was, "Not bad." I'd been one of only a handful of readers to notice, he said.

In Kinder's circle of literary outlaws, this sort of thing happens all the time. Kinder has a letter from Tobias Wolff, for example, congratulating him on wittily plagiarizing Wolff's own work. Kinder and Carver were even closer friends, friends who shared just about everything: women ... stories ... stories about women ...

"When I was 17, I ran away from home. I ran into a lot of trouble," Kinder says. Breaking a literary rule "doesn't exactly rise to the level of holding up a cab around Atlantic City."

What does he think of Frey's transgressions? Not much. In fact, "I could have just as easily written Honeymooners as a memoir," he says. While he acknowledges "collapsing" some events -- distilling several incidents into a single event and so on -- he says, "There's no lie in that book." If he had done it as a memoir, "I wouldn't have changed anything, just what you call it."

I won't blame you if you find this disturbing. (In fact, Kinder may have said that in the expectation of such a reaction: If it weren't for rules, what would literary outlaws have to break?) If we can't trust that a writer's words are his own, how can we trust what he says? If Frey calls something a "memoir," isn't he trading on the thrill readers get from a "true story"? Doesn't that mean he should stick to the facts?

Then again, I have postmodern-philosopher friends who say that "sticking to the facts" relies on a discredited belief in objective reality. And that putting a premium on originality depends on an outmoded "essentialist" view of the Author As Promethean Genius. These friends say that both the creation and interpretation of a work of art is the result of its cultural context. Thus, every work of art is a series of borrowings from somewhere else. Some borrowings are just attributed more clearly.

Kinder doesn't have much use for such French pomo blather, which he refers to as "Froggy theories." But he has even less use for those who say words on a page can (or should) purely represent the real world. People think art should hold a mirror to reality, he says, "But think about what a mirror does. It doubles the distance, and reverses right and left. Is that realism?"

Nor is the question "Is this a true story?" very important to him. All stories are true, if they are well written. The question is what they're telling the truth about.

So what advice would he give writers struggling with such the ethical issues raised by writers like Frey and books like How Opal Mehta Got Kissed, whose author apparently plagiarized parts of the novel?

"Advice?" he asks. "The best thing I could do is not give them any."

After a moment, he adds, "Don't get caught." But he's smiling when he says this, and I'm not sure he means it.