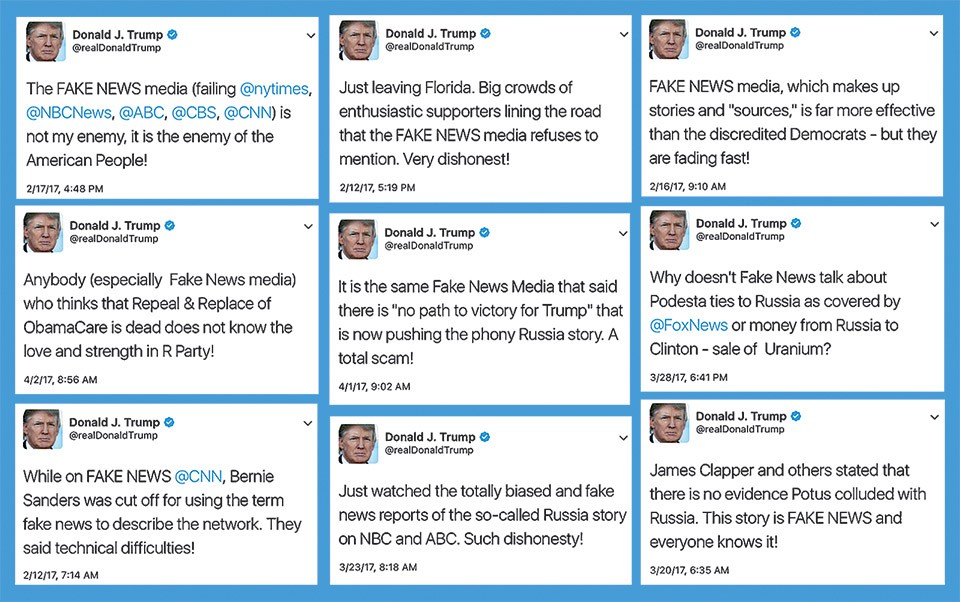

There’s good news and there’s bad news: Use of the term “fake news” might have peaked. That’s good news because people are realizing that the label is growing meaningless — an insult tossed at information you don’t like. But it’s also bad because, well, fake news itself hasn’t gone away. We live, after all, in a nation whose president is the loudest purveyor both of outlandish hearsay and of accusations that actual journalists are “enemies of the people.” Official lying is as old as civilization. But today, confronted with “alternative facts” spread instantly online, we’re losing our grasp on what counts as reliable information — and perhaps even on reality itself. There’s a real risk that we’ll just give up on independently verified facts, and — deer caught in the headlines — remain mesmerized instead by the comforting words of our preferred pundits, bloggers and demagogues.

>> Sensationally worded headlines (“you won’t believe,” “x CRUSHES y”) routinely indicate clickbait

>> Urls ending in “.lo” or “.co” often indicate comedy or satire sites

>> No byline

>> Sources not fully identified or only unnamed sources

>> Cited events are not dated to provide proper context

How To Kill Fake News

>> If a story is breaking, wait: Facts will change shortly

>> For any given story, seek out multiple sources of information

So let’s define fake news as words and images either intended to deceive, or shared without regard for their truth. This issue of City Paper is meant to help you to both identify such “bad news” and find “good news” to take its place.

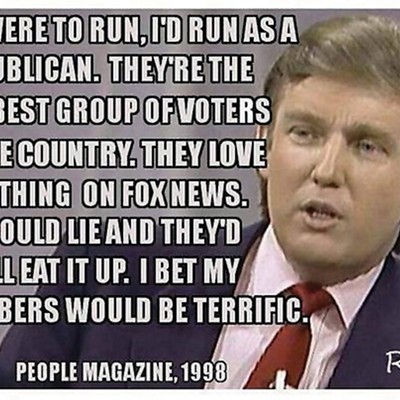

Fake news takes many forms. Some is simply clickbait (including made-up articles that don’t match their ridiculous headlines). But few fake-news articles are entirely fictional. More likely, and more insidiously, that deceptive article on your social-media feed (where so many of us get our news) involves something subtler, like made-up quotes buried in otherwise factual stories, or cherry-picked statistics set in misleading contexts. Another problem is the blurring of the lines between “news” and “opinion.” Point Park University journalism professor Steve Hallock cites the case of TV’s political “shout shows,” where a given guest, far from an expert on the topic at hand, might be an unacknowledged “surrogate for a politician or elected official who has a particular point of view to sell, or … simply a long-time right-wing or left-wing commentator with few credentials other than having been published or aired by a cable channel or publication with a political agenda.”

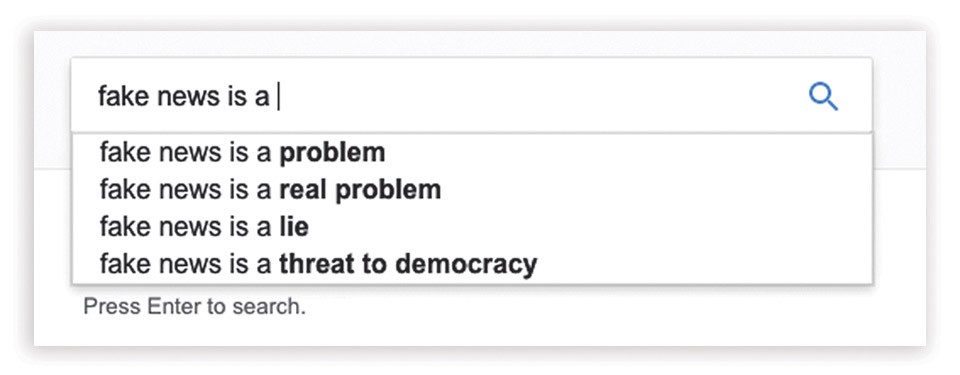

Fake news knows no ideological or partisan bounds, and its spread is facilitated by factors including our tendency on social media to converse with like-minded folks; our habit of believing what friends tell us; and search engines’ efficiency at feeding us the news our reading habits suggest we want to see. We all live in some sort of information silo.

- A guide for navigating "good news" and "bad news" in the fake-news era

- In the current news climate, it's time to question where news outlets get their information

- Media consumers are taking memes at face value, but they often contain misinformation

- TV news is not the best place to "go local"

- MedLocal TV newscasts keep it local

- The Eight Stages of a Golden Shower (Story)

- Evisceration Nation

- How Journalists Can Mislead Readers: An Annotation

- Pittsburgh Left: Our paper may be alternative, but our facts are on the money

- Real News About Fake News Quiz

But it’s also important to understand what fake news isn’t. It’s not satire — even if your uncle thinks that Onion story you shared on Facebook is real. It’s not opinions you disagree with (unless the pundit twists facts). It’s not honest errors by journalists. It’s not even necessarily bad journalism; for instance, while factual assertions by public officials should be fact-checked, a reporter who can’t manage that task by deadline probably isn’t trying to deceive you (unless there’s a pattern of leaving untrue assertions unchallenged). Nor is fake news the accurate reporting of patently crazy-pants statements by (say) the president of the United States — though even reporters who call out such lies can be complicit in distracting us from more important issues.

How to proceed? Identifying fake news can be as easy as checking the url. Odd domain names, and links ending in “.lo” or “.co” often signal fake-news sites, librarians say, and “wordpress” or “blogger” in the url usually signal an opinion site rather than a credible news source. To evaluate further, click on sites’ “About Us” tabs. Other red flags include sensationalistic or all-caps language (“x CRUSHES y”) and the absence of bylines on articles. Also note original publication dates: Marnie Hampton, a teaching librarian at the University of Pittsburgh’s Hillman Library, cautions that old web pages “seem to rise like zombies” to spread outdated information.

Statistics or other facts offered without sources should raise suspicions; if a source or study is cited or linked, check that out, too. For any given news story, Hampton adds, don’t rely on just one source: See whether and how the story’s being reported elsewhere. Sites like PolitiFact, FactCheck and Snopes exist to ferret out the truth about rumors and politicians’ public statements. And if a story is breaking — the latest bombing or political scandal — don’t draw conclusions based on the usually sketchy information and speculation (often ideologically charged) that’s immediately available. “See what the story is in 24 hours, when people have more chance to do background research,” Hampton says.

Fake news would start to die if each of us would simply check out articles and factoid-based memes before sharing them. And in fact, journalism professor Hallock contends that the new wave of official lying has renewed healthy skepticism in the press: “I do think that Trump has changed the landscape a little, because he’s forced some people to do some doublechecking to make sure there’s not another side to it.” Hallock notes rising subscription rates for The New York Times and other reputable papers. “I think Trump is actually strengthening journalism and I don’t think he intended to do that,” Hallock says.

But what are the traits of credible news sources?

Inevitably, all journalists and newsgathering institutions (even this one) have biases. They choose to tell a given story from a particular perspective. They include some facts and leave out others. And they frame those facts in a certain way. So because not even the most responsible journalist is perfectly objective, on any given topic it’s wise to consult news sources from across the political spectrum — even international viewpoints.

Hallock, for his part, says that the best criteria for good journalism isn’t objectivity, or even the ever-malleable “balance.” He prefers “thoroughness.” Having “both sides” of a story trade accusations and rebuttals isn’t always illuminating; most stories, in fact, have way more than two sides. Journalists should present as many of them as possible, double-check facts and put them in context.

In a complex world, the willingness to go in-depth, in longer formats if need be, is crucial to finding the truth. And if that takes more effort from journalists, it’s going to require more effort from readers, viewers and listeners, too.