"Architecture or revolution!" was LeCorbusier's clarion call in the 1920s, and the words have echoed through the ensuing decades. Never mind that "Corb" was more like a fascist than a revolutionary: Nearly every architect, no matter how modest his or her kitchen additions or storefront renovations, has a bit of the world-changing firebrand inside. It's just not the same with podiatrists or actuaries.

But what happens when architects really do have a chance to participate in a revolution?

Architect and historian John Loomis, author of Revolution of Forms: Cuba's Forgotten Art Schools, addresses such a moment in his book, as well as in a lecture and a short film, Variaciones, at the Regent Square Theater on Sun., Feb. 13. The event is sponsored by Pittsburgh Filmmakers and the Mattress Factory as part of an ongoing series about Cuban culture.

The national art schools of Cuba were built in the early days of the Castro regime, structures of exuberant and period-appropriate modern architecture. Now, these case studies in sub-tropical utopia are deteriorating -- seemingly ready, like Castro himself, to topple at any minute. Unlike the hirsute octogenarian dictator, though, the buildings are actually beautiful, though still tragic, in their decay.

This rapid decline was not the original intention. During a golf game in 1961 at the Havana Country Club, unlikely duffers Fidel Castro and Che Guevara decided to turn the elitist enclave into a campus for five national schools of art, all the better to make the country's aspirations for artistic excellence and national cultural expression more powerful and more accessible to the workers -- at the expense, of course, of the deposed elites.

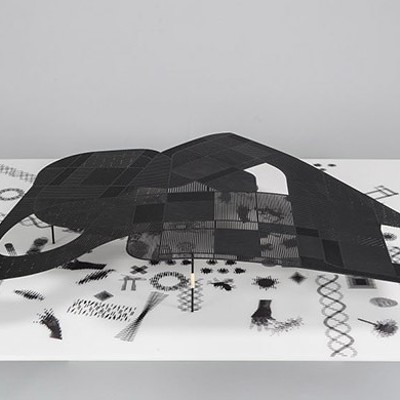

The talented young Cuban architect Ricardo Porro was put in charge of the project, and he persuaded Italian colleagues Roberto Gottardi and Vittorio Garatti to lend their talents to the revolution. They organized a vast team of architects, engineers and construction workers to build five separate but related complexes for Dramatic Arts, Music, Modern Dance, Ballet and Plastic Arts. The schools are grouped at the edge of the property, allowing woods and water to intermingle. Their emphasis on local materials, primarily brick, may have been necessitated by the restrictions of embargoes, but the approach nonetheless enhances the sense of tradition, craft and texture.

Perhaps most exciting is the sense of being sheltered by living, benevolent creatures that visitors get from being under one of Porro's eccentrically shaped domes. Octagonal here and round there, connected by winding passages, and often open at ground level, they are made of Guastavino tile. The system of thin ceramic bricks to enclose vast spaces originated in medieval Spain but gained wide use in 19th- and 20th-century America -- not least at Carnegie Tech in Pittsburgh-- before industrialized concrete ended its use. By the 1960s, the elegant material was a throwback necessitated by circumstance, but it is nonetheless as lithe and buoyant as the dancers whose performance space it encloses.

Sixties modernism in the United States is all too often overbearing and banal. But the winds of change, to say nothing of those from the Caribbean, breathed wonderful freshness into these structures.

Perhaps it was all too good to be true. Forced to choose between architecture and revolution, Cuba chose revolution and quickly Sovietized. The stunning but incomplete art schools were suddenly vilified as elitist, their hopeful and energetic architectural imagery replaced by anonymous, industrialized Kruschevian designs -- Cuba's new standard. The schools' continuing use has decreased, hampered a lack of funds and a near-absence of maintenance.

Loomis engages his subject with scholarly rigor, but he is also an advocate whose efforts are slowly bringing results. The Cuban government has offered funds, albeit meager ones, to begin restoring the schools, while increasing international awareness is raising prospects for a more comprehensive financial campaign.

At one level, this compelling tale of splendid architecture gives lie to LeCorbusier. The great form-maker wanted his followers to believe that architecture at its most powerful could replace revolution. Yet here we have some of the best architecture of its era, and its splendid and humane values were unceremoniously squelched by totalitarianism. If not for John Loomis and a few other advocates, they might be lost entirely.

Then again, though Castro's revolution will surely die when he does, the architecture may yet live on.