More people choose to commit suicide from the Golden Gate Bridge than at any other spot in the world.

Inspired by Tad Friend's 2003 article in The New Yorker, "Jumpers: The Fatal Grandeur of the Golden Gate Bridge," filmmaker Eric Steel set up several cameras aimed at the iconic structure that spans the entrance of the San Francisco Bay. Throughout 2004, he and his crews videotaped the bridge continually during daylight hours. The cameras captured exquisite vistas, myriad tourists, cars and birds that share the bridge -- and nearly all of the 24 people who jumped to their deaths from the pedestrian walkway that year.

The first jumper was recorded three months after the bridge opened in 1937.

The film Steel built from his collected footage, The Bridge, is not a typical documentary. There is no voice-over, no on-screen factoids (there are more facts about the Golden Gate Bridge in this review than in the film). Instead, Steel mixes picture-postcard images of the world's most recognizable bridge with scenes of activity on the busy span -- strollers, joggers, tourists, jumpers. Providing the film's narrative are interviews with family members and friends of jumpers, inadvertent witnesses and rescuers, and, remarkably, a jumper who survived.

From the bridge's span to the water below is a drop of 220 feet. The fall takes about four seconds.

As the interviewees fill in back stories -- the prefaces of mental illness, despair, love troubles -- and poke through their own grief and guilt, the film becomes a meditation on life and death, on the unknowable quality of the human soul, and the devastating ripple effects of suicide.

The Bridge is also about the specificity of the locale, as interviewees ruminate about the power of the bridge, and its remarkably public setting. One friend ponders the allure of the bridge for suicides, musing that jumpers never get to enjoy the aura of romanticism a bridge-jump confers: "They're dead," she notes bitterly. "It's an empty promise."

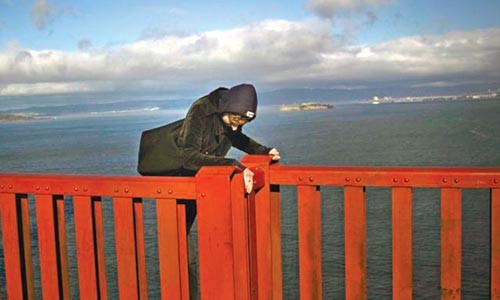

The safety railing is four feet high.

It may be as simple as ease: Jumping off the publicly accessible walkway requires no preparation or accessories; once over the edge, there's no escape hatch; the dark water below creates the illusion that you will be swallowed up cleanly into nothingness; a bridge jumper stands poised on the very edge of the continent, on a structure named for a transition point. Every tourist has peered over the edge and wondered. Hypothetically speaking, the attraction of jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge is knowable, even as we never understand why people take that one final step.

More than two-dozen jumpers are known to have survived.

On occasion, Steel supplements his film with footage and stories provided by coincidental witnesses. One of them, Pittsburgher Richard Waters, was taking scenic photos when a young woman climbed over the railing right in front of him. Waters captured several amazing images, before realizing what was happening. He then single-handedly pulled the woman back to safety, an act captured by one of Steel's cameras. Interviewed later by Steel, Waters cites the unrealness of the watching the near-suicide, and notes how his photo-taking created an unnerving emotional distance. The same could be said of Steel and us. As we witness the suicide scenes bracketed within the context of the film's artistic goals, the reaction is apt to be clinical and detached.

The unofficial tally of jumpers is more than 1,300 (authorities have stopped keeping public counts).

The Bridge is not without controversy. There are societal taboos about showing on-camera deaths (Steel shows four jumps clearly, and two splashes seen from a distance). There's also our knowledge of Steel as an informed spectator. After the film's release, he claimed in interviews, including one on ABC's 20/20, that his camera crews called for help if they suspected a potential suicide, and that their calls resulted in several saves. Yet it's uncomfortable to realize they kept the cameras running.

Jumpers hit the water at about 75 mph.

Admittedly, I had more reservations about the film before seeing it. I worried that it would be exploitive or sensationalistic; that watching the jumps would be horrifying; that the family interviews would be painfully uncomfortable -- and that as a viewer I'd be complicit in it all. Steel's film is admittedly an act of voyeurism, but the material is handled sensitively, and the end result is quietly provocative. Suicide is typically a hush-hush topic, mired in shame and secrecy. It's rarely probed in popular media, and The Bridge is a rare nonjudgmental forum for unvarnished discussion.

On average, somebody jumps off the bridge every two weeks.

I spent the first 20-odd years of my life in San Francisco, where the Golden Gate Bridge was noted primarily for being a traffic nightmare and a place to take visitors. In the background noise of a city endlessly invested in dramas, people jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge seemed as matter-of-fact, and as expected, as the fog rolling in by late afternoon. Yet Steel's film made me see the bridge anew (in all those years, did I neglect to notice how gorgeous it is?), and to reconsider its macabre pull. My own knowledge of the landscape around, on and even under the bridge made such footage deeply familiar, but also added an unnerving fascination, as if the film were revealing some heretofore unknown tragic history of a friend.

Starts Fri., Jan. 12. Harris