Amid the summer comedies and heroic action pics comes Standard Operating Procedure, a decidedly more downbeat offering from documentarian Errol Morris intended to parse meaning from the infamous Abu Ghraib photographs.

Morris' goal is to re-examine those photographs, taken in the fall of 2003 at the Baghdad prison, and made public to widespread outrage a few months later. The photos, snapped by low-ranking U.S. military personnel, depicted both Iraqi prisoners in questionable circumstances as well as soldiers interacting bizarrely with the detainees. Following orders? Horsing around? Knowingly engaging in humiliation and even torture?

SOP seeks to provide the context for understanding how this aberrant scenario (if indeed, it is that) could have occurred, while simultaneously querying the "truthfulness" of an image. Thus, looking "outside the frame" is both literal (some photos were cropped, or otherwise failed to show the full scene) and metaphorical: What was the big picture, the experiential data, that resulted in these 270 photographs, and how does this knowledge balance with what we thought we learned from the images?

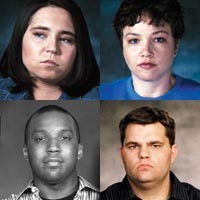

To this end, Morris interviews about a dozen participants, who were either on the scene at Abu Ghraib or later involved in the criminal case that ultimately found seven soldiers guilty. The soldiers are his big "get," especially the poster girl for the whole mess, Lynndie England.

Essentially, they tell their sides of the story, explain how or why certain photos were taken, and, to varying degrees, express regret, remorse, anger and indifference. Living at the prison was shitty and scary; they liked to take funny pictures of each other (i.e. posing for banana blowjobs); they were just doing their jobs; and there were worse things that happened that nobody got caught doing.

SOP asks us to consider the elusive truth of photography, but it might as well be about the dubious nature of first-person accounts, presented here with virtually no probing. (Morris also has admitted in interviews that he paid the participants, but that is not noted in the film.) Some interviewees offer explanations which might mitigate the original impact of the photo but there are also plenty of excuses and defensive posturing.

Ironically, the on-site participants we don't hear from are the prisoners. Morris says in press materials that they couldn't be located, but needless to say, that's a big missing component.

Recent films about Iraq and the war on terror -- from low-budget docs to meaty investigations and glossy Hollywood tales -- have failed to motivate many viewers into the theater. In truth, most of these works deliver a big bag of depressing, and even the must-sees of the batch are merely edifying, rather than entertaining.

It's possible that Morris, who enjoys about as high a profile as one can as a film essayist with a penchant for difficult and morally ambiguous topics, may entice more feet into theaters. And, if this is your first Iraq doc, you'll likely find SOP to be profoundly disturbing and potentially eye-opening. But, for battle-hardened consumers of myriad books, films and television programs about the various failures of the Iraq mess and the related war on terror, SOP feels both late to the table and inadequate.

As an examination of this specific event, the film offers valuable, if highly subjective, perspectives. But as a broader critique of how our country lost its moral compass, it falls far short, particularly when measured against the devastating Taxi to the Dark Side. Alex Gibney's recent documentary was a straightforward investigative work which methodically traced the new normal -- from Guantanamo Bay to Afghanistan to Abu Ghraib -- and left no doubt that the abuse originated at the top, was widespread and, with few exceptions like the crew busted at Abu Ghraib, remains largely unaccountable. SOP, in its micro focus, fails to make its larger argument stick.

It doesn't help that Morris -- for the sake of artiness, or simply to stretch out time -- adds a lot of visual filler. Gauzily filmed, slow-motion recreations such as a naked dark-skinned man crawling across a wet floor, the snarling muzzle of dog or a Nerf ball bouncing in the prison corridor, while these scenes are described by interviewees, add little to our knowledge. Additionally, the use of clearly manipulated images is a strange buttress to a supposed think-piece about the potentially slippery and inflammatory nature of photography. Toss in a distracting and unnecessarily dramatic score by Danny Elfman, and what should be a gut-punch becomes instead a cool video moment.

Morris' film is open-ended enough that each viewer may take away something different from the rumination and eyewitness accounts. I don't find it a big mystery that young, bored people placed in weird, scary assignments with little training or supervision might revert to group-think bad behavior -- and take photos of their late-night hi-jinks. The bigger outrage is the mutations in our institutions that condoned and encouraged such shocking disregard for human rights, but that way-outside-the-frame case has been made better elsewhere.

Starts Fri., Jun 6. Regent Square