When they're not busy trying to keep the lights on or mounting their next show, arts folk sometimes chuckle over how the public thinks the arts are funded. We're talking, obviously, about nonprofit arts — not Avatar, The Book of Mormon and Kenny Chesney, but museums, galleries, literary series, and music, theater and dance troupes. And we're mostly talking about small to mid-sized organizations, not those affiliated with universities or large enough to have their own endowments. (Though the Carnegie Museums of the world must fundraise, too.)

In short, arts money might not come from, or go, where you think. Here are seven myths about arts funding.

Art Is Cheap to Make. Our region's hundreds of arts groups range from shoestring operations to multimillion-dollar outfits with their own venues and salaried staff. But that modestly produced play by a small theater company probably wasn't staged for a song. These things take time: Even the thriftiest troupe pays its cast and crew, and small salaries add up. Include costumes and sets, rentals and insurance, and you've eaten most of the budget of a troupe like Unseam'd Shakespeare Co. A typical Unseam'd show costs $50,000 — and, says founder and artistic director Laura Smiley, she even donates her own small salary to the cause.

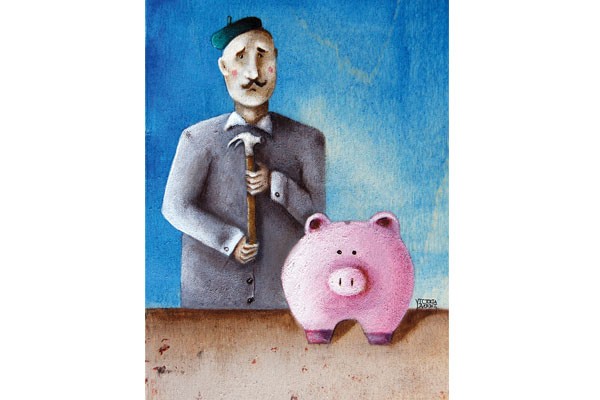

Admissions Cover Expenses. In fact, nonprofit arts groups do well to make even half their budget through all earned income (including things like merchandise and fees for classes). Small performance troupes perhaps have it roughest: Sales of tickets priced at $23-25 account for just 30 percent of Unseam'd Shakespeare's budget, for instance. And the Kelly-Strayhorn Theater, known for its cutting-edge dance programs, makes just 10 percent of its revenue from admissions, says executive director Janera Solomon. (That's roughly the same percentage the Carnegie Museums collect, by the way.) Groups make up the difference through individual donations and other giving. That leads to myths like ...

Foundations Pay for Everything. Pittsburgh's foundations, most agree, back the arts strongly. Foundation grants are crucial to most arts nonprofits, and such giving has largely recovered from the 2008 crash. But competition is fierce: According to the group Grantmakers in the Arts, only about 11 percent of foundation dollars nationally benefit arts and culture (compared to 24 percent for education and 22 percent for health). And most foundations would rather support specific projects than underwrite general operating costs: Unrestricted operating support accounts for just 16 percent of foundations' arts giving. So even groups that receive project funding must look elsewhere to cover ongoing expenses like salaries.

Government Heavily Subsidizes the Arts. This might be the biggest myth, thanks partly to 1990s headlines about National Endowment for the Arts funding for controversial artists. But the NEA's 2012 budget was just $146 million — less than Kickstarter dispensed. Pennsylvania Council on the Arts' budget is $8.2 million, half of what it was five years ago. All government arts spending combined (federal, state and municipal) is $1.12 billion, or $3.56 per U.S. citizen. (By far the lowest figure in the developed world.) Adjusted for inflation, says Grantmakers in the Arts, "total government funding for the arts has contracted by 31 percent since 1992." Locally, most public arts funding comes from the Allegheny Regional Asset District, a resource whose influence Pittsburgh Filmmakers/Pittsburgh Center for the Arts head Charlie Humphrey calls "profound." But the county's 1 percent sales tax doesn't, as some might believe, solely benefit the arts: Half that money goes to local governments. After ARAD splits the other half among parks, libraries, stadiums and such, the arts receive about $9.9 million — one sales-tax dollar out of 20.

Funding the Arts Is Frivolous. Besides enriching us culturally, arts spending generates economic activity. Advocates like Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council chief Mitch Swain point to a 2012 Americans for the Arts study that found that arts organizations and their audiences spend $686 million a year in Allegheny County and support the equivalent of 20,000 full-time jobs.

Art Groups (and Artists) Spend All Their Time Making Art. "There are precious few artists in town who can make a living off their work," says the Heinz Endowments' Janet Sarbaugh. Most have day jobs; many of the city's top stage actors, for instance, teach. Meanwhile, arts administrators like Silver Eye Center for Photography executive director Ellen Fleurov say they spend more than half their time looking for funding. Some of that energy is expended finding earned income. Art groups, notes Solomon, can often make more money holding classes than by presenting art. Humphrey says Pittsburgh Filmmakers/Center for the Arts gets 65 percent of its revenue through its classes, screenings and hall rentals (for weddings and such).

Artists Are Bad With Money. "The very best artists are really good at it. They have to be," says Solomon. "You give them $1 and they can make it last longer than anyone else I know." Artists have a bad reputation with money, she says, because rather than managing money, they'd prefer to just make art.