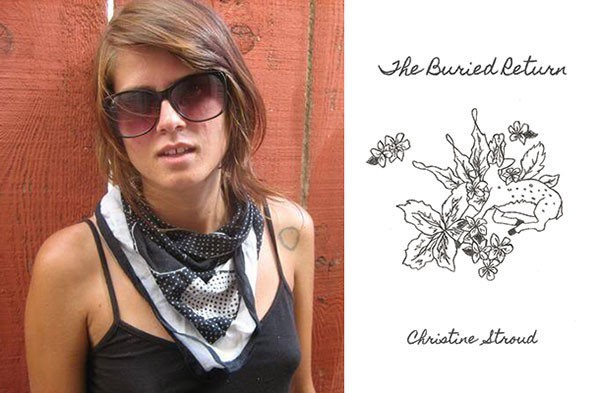

The Buried Return

By Christine Stroud

Finishing Line Press, 25 pp., $12

In Christine Stroud's strong debut chapbook "The Buried Return," songs of innocence are sung through the veil of experience, songs of experience are touched by an innocence that won't yield.

About half of these 20 poems by Stroud, associate editor of Pittsburgh-based Autumn House Press, recall youth or childhood (usually the speaker's). The taut, plain-spoken pieces recall episodes from quiet ones (like a girl seeking attention from her hard-to-please grandmother) to more dramatic. In the prose poem "My Last Spanking," the speaker recalls being age 7 and defiantly refusing to cry when her father punishes her for pretending to be Christ on the cross.

Indeed, Stroud's tone in these poems of youth is itself defiant, devoid of regret or remorse. Even when she's recounting an obvious injustice, like the savage beating of a high school girl whose assailants call her "dyke," Stroud's style remains determinedly clinical: "Your queerness / was there, smudging those boys' / decency, like the dark gray circles / on the standardized test sheets."

The collection's second half is set in young adulthood, and while the style doesn't change much, the perspective alters subtly. The speakers seem both more engaged and more easily wounded. In one, the speaker second-guesses her inability to kill a badly injured cat. Others, like the four hard-hitting poems in a series all titled "Relapse Suite," confront alcoholism and drug abuse with a heightened awareness of consequences.

True, even in such poems the observer feels slightly detached, looking back without judgment. In "Lotophagi," depicting partners in opiated bliss, Stroud writes, "Our eyes won't open / they are dripping / with burnt yellow tar. / Late afternoon sweats. / I like you best / in lotus honey." Yet the collection's surreal title poem signals something like regret as the speaker discovers that her dead grandfather, dead grandmother and a suicidal friend have returned as putrefying zombies. Even as she admires how "[s]unset light pushes through their decayed / stomachs," the speaker is apologizing for not treating them better in life.

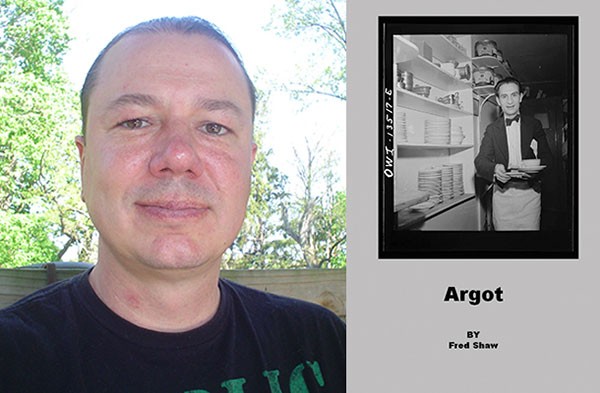

Argot

By Fred Shaw

Finishing Line Press, 30 pp., $12

In his fine debut chapbook, Argot, Fred Shaw writes about many things: music, the humiliations of youth, a father. But as suggested by the black-and-white cover photo of a bow-tied, white-aproned waiter grinning in a pantry, about half of these 26 poems are about (or at least take place at) work.

Shaw teaches writing and literature at Point Park University and Carlow College. (He also contributes occasional book reviews to City Paper.) But as he writes in his author bio, for the past 25 years, he's spent a "parallel life" in the service industry. That experience informs poems like the title verse, whose speaker introduces himself in a "sweaty restaurant kitchen" and refers to his own mother's series of jobs in food prep. The speaker and his mother play Scrabble and discuss their fingers, nerve-flayed by daily grinds; the poem concludes by sounding what might be this collection's keynote, with each character "searching / for the phrase that captures what it is / to feel at once / both capable and small."

These working-life speakers take pride in jobs well done, yet with complete awareness of their designated roles in a "culture of demand." One speaker's consciousness is such that he can't eat frozen strawberries without thinking of the working stiffs who hauled them cross-country. Still, though their perspective is implicitly political, such poems are far from sermons. Usually they're conduits to more universal existential explorations, as when kitchen workers scarfing up a fallen plate of seafood ("the first scallops / some of us had ever tried") are located by the speaker "in a heaping world that needs us to believe / we can be oceans, pushing waves / toward a shoreline we can't see / the worn down, far-off places of ourselves."

Shaw hews to the "no ideas but in things" school. But the inanimate objects that serve as his "trigger[s] to pull on the past" (as he says in one poem) aren't limited to kitchen tools. A long-owned plastic trash bin embodies a decade rapidly slipped by. A red pickup truck recalls a speaker's father. "The hard plastic seats of the transit bus" spur memories of three times the speaker felt "like ... a child / and all my bombs ... water balloons."

From describing two wannabe punks afraid to exit their car at a rock club to a speaker contemplating his decommissioned work pants, Shaw brings a powerful sense of humanity, time passing and the yearning for transcendence.