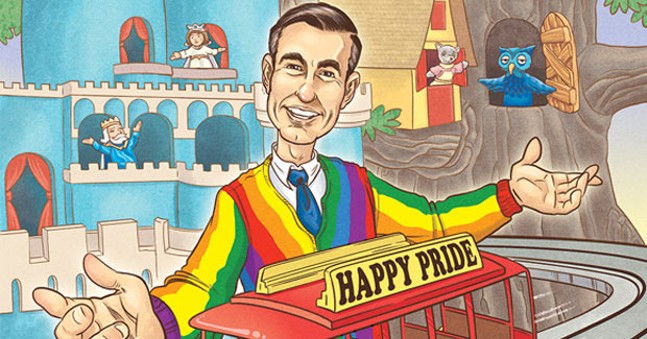

It was a simple concept: a children’s show that taught life lessons in a calm, friendly manner within a puppet-filled fantasy world and a fictionalized suburban neighborhood. It grew into so much more.

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood became a staple in countless households, transformed educational television and made a star out of its quiet, thoughtful host, Fred Rogers.

Rogers is easily and fondly remembered by many — especially in Pittsburgh, where Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was filmed — for his soft demeanor, trademark cardigan sweaters and that gentle invitation, “Won’t you be my neighbor?”

But in the years since Rogers’ death in 2003, it’s become easy to forget one thing about him and his show: many of the ideas presented on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood were radical and uncompromising, breaking new ground for more than merely TV.

In one of the show’s iconic scenes, Rogers spends one particularly hot summer day in the neighborhood outside, cooling his feet in a plastic kiddie pool. Officer Clemmons, the local police officer, comes by. Rogers invites Clemmons to join him. The two enjoy the water together for a while, then they dry each other’s feet off with a towel.

“It was such an easy thing to do, profoundly simple and easy for two friends to sit down and put their feet in the water to relax on a hot summer evening,” says François Clemmons, who portrayed Officer Clemmons.

This scene aired in 1969, during the end of the Civil Rights Movement and about a year after the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

“White people did not want black people to swim in their swimming pools and were putting acid and other kinds of poisons in [pools],” Clemmons says. “So it was dealing with something that was very serious in this country. But here we were, showing an alternative, a different way, an option, saying to people, ‘You know you don’t have to do that.’”

This was how Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood presented numerous topics, many of them rather controversial for children’s television. Race, war, death and divorce were all discussed, but Rogers’ calm, straightforward manner made the topics real and approachable.

Connected over a week’s worth of episodes, one plot line addresses change, violence and border issues. Fearful of change, King Friday XIII (the puppet ruler of the Neighborhood of Make-Believe) orders a border wall to be built to keep the neighborhood safe. Lady Aberlin takes balloons, tied with messages of peace and love to them, and floats them across the wall, convincing the king to tear down the wall. Those episodes were the first five shows.

The desire to communicate adult ideas with children in an honest, thoughtful manner was what drove Rogers to create his show. While studying to become a Presbyterian minister, Rogers glimpsed a children’s TV program that was loud and comical. He was later quoted as saying, “I went into television because I hated it so, and I thought there's some way of using this fabulous instrument to nurture those who would watch and listen.”

Rogers’ nurturing wasn’t limited to children, though. To Clemmons, he became a father figure and a mentor.

Clemmons, who is gay, struggled with his sexuality for much of his early life; his marriage to a woman ended in divorce. From the start of the show, Rogers and Clemmons were forced to balance Clemmons’ sexuality with the show.

“The decision was that I could not be open because there were many people in this country who would not watch the program if they thought Officer Clemmons was openly gay,” Clemmons says. “He said, ‘I have to think about that. I want them not to think about you and your sexuality, I want them to think about the things that I want to teach.’”

Clemmons understood Rogers’ reasons, calling them “totally legitimate." What mattered to Clemmons was that Rogers personally accepted him as a gay man.

“He understood that I needed time, and he gave me that time,” he says.

While Officer Clemmons never came out on the show, he was crucial to Rogers’ message of love. In his final appearance on the show in 1993, Rogers and Clemmons sang “Many Ways to Say I Love You” as they soaked their feet in the pool a second and final time.

“I carried the hope inside of me that, one day, the world would change,” Clemmons says. “And I do feel that the world still has not totally changed, but it is changing. We’re getting there.”

Explore more of the life and career of Fred Rogers with the new documentary, Won't You Be My Neighbor?