Fearsome, strange, and emblazoned in crisp black and white, Shepard Fairey's stylized image of French wrestler Andre Roussinoff (a.k.a. Andre the Giant) helped catapult the artist from DIY prankster to a street-art folk hero … who's now the subject of career retrospectives like the one coming to The Andy Warhol Museum.

Many consider the "Obey Giant" campaign to be Fairey's magnum opus. Yet devout followers were surprised when Fairey crafted his now-ubiquitous "Hope" poster endorsing Barack Obama's presidential bid.

The image was adopted by the campaign and later inducted into the Smithsonian Institute's National Portrait Gallery, in Washington, D.C. But in the underground art scene, Fairey's reputation took a beating. Many spurned him for endorsing a mainstream candidate.

"There's been backlash to my success, which always hurts my feelings, because I feel like I'm still as scrappy and rebellious as ever," says Fairey, 39, in a recent phone interview from his Los Angeles studio. "But at the same time, it has opened up an audience of people that probably never cared about street art or grassroots activism."

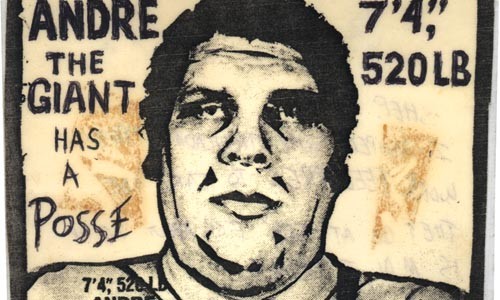

The South Carolina native began his art career almost by accident. In 1989, when Fairey was a Rhode Island School of Design student, a friend asked him how to make a paper-cut stencil. On a whim, Fairey clipped a newspaper image of Andre the Giant as a visual aid.

"[My friend] tried to cut the image with an X-acto knife, but aborted the mission in frustration," Fairey writes in Supply & Demand, the nearly 500-page tome compiled for his solo retrospective last February at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. "I finished the job and wrote 'Andre the Giant has a Posse' on one side [of the image], with his height and weight, 7'4", 520 lbs., on the other side."

Fairey turned the image into a sticker, and from there, it spread quickly, popping up in New York, Boston and elsewhere. Its appeal was like a secret handshake sealed with a wink: You were in the posse, or you weren't. And people wanted to be in on the joke, even if they didn't know what the joke was -- which tapped into philosopher Martin Heidegger's theory of "phenomenology" that Fairey had adopted as a manifesto for his obsessive street campaign.

Since then, much has changed.

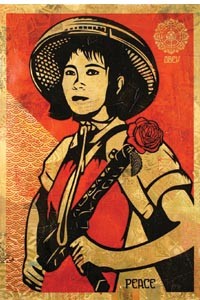

Fairey's work, while remaining simplistic in its black, white and red aesthetic, has evolved to encompass commercial and fine art, and political messaging -- often blurring the lines between marketing and street art, commerce and activism. He has embraced the angular lines of Constructivism and overt visuals of Cold War propaganda to powerful ends. Anti-war and anti-authority themes are prevalent in pieces like "Greetings from Iraq" (2007) and "Uncle Scam" (2007). And he's championed environmental causes, for example touting clean energy in posters for Moveon.org.

Still treading the line between populist and fine art, Fairey now crafts ornate, multi-layered, collage-like street installations that he then reproduces in a gallery setting. This past August, Fairey wheat-pasted many such pieces on buildings in Pittsburgh neighborhoods with the help of the Warhol Museum -- where his sprawling, multi-floor solo retrospective, Supply & Demand, opens Oct. 17. The show, adapted from Fairey's Boston exhibit, features 250 pieces. Fairey says he'll also include new works.

"I thought it was a pivotal moment to look at the work," says museum director Tom Sokolowski. "Shepard's someone who has continued in his activist ways but also has been making objects, designs for clothing, et cetera," Sokolowski adds. "And that's a moment -- especially with someone who has street cred -- where people start to say, 'Oh, well, has he turned around?'"

Sokolowski believes Fairey has not abandoned his roots, but instead uses his newfound platform to communicate social and political issues important to him.

But finding a balance between high-profile gallery exhibitions and his continued street campaign has proven difficult. Last February, en route to his Boston opening, Fairey was arrested by Boston police on a warrant stemming from a prior graffiti case.

"I was charged with 34 felonies," he says. "They wanted to stop me because I was a symbol of illegal street art. [Now] I'm just adapting what I do as a street artist to what's going on with my legal situation. But to me, having work up in public is extremely important." Fairey ended up pleading guilty to two misdemeanors and received two years' probation.

Today, Fairey is more than a pop-art phenom -- he is a husband and father of two. He runs his own design firm, Studio Number One, and art gallery, Subliminal Projects -- the houses that Andre built.

"My work's never been about the idea of saying, 'Screw you, I'm going to do what I want and it's better that it's illegal because it's an act of defiance,'" he says. "That was sort of a de facto result of not having any connections. But it's always been about sharing the work."

Shepard Fairey: Supply and Demand Artist talk and opening reception: 6-10 p.m. Sat., Oct. 17 ($15-35). Andy Warhol Museum, 117 Sandusky St., North Side. 412-237-8300 or www.warhol.org