"Where do buildings come from?" One might ask as if the creation process were a wonder of nature. You see, when an architect and a contractor love each other very much, the architect inserts plans in the contractor's materials, and after months of labor, a building is born. Of course, the missing ingredient here is neither stork nor obstetrician nor client, but engineer. We may not think twice or hear even once about the role of the engineer in most conventional structures, and a world of prevalent post-and-beam structures rarely asks us to.

But enter Cecil Balmond, the London-based, Sri Lanka-born chairman of the internationally renowned, nonpareil engineering firm Arup, and much contemporary architecture seems to have a third (or second or first) parent.

Balmond, whose installation H_Edge is on display at the Carnegie Museum of Art's Forum Gallery, speaks at the museum on Feb. 6. Architectural critic Charles Jencks noted in 1997 that among his 15 favorite avant-garde buildings of the day, Balmond had been involved in more of them than any single architect. Balmond has collaborated with most if not all of current avant-garde starchitecture: Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind, Álvaro Siza and Ben Van Berkel.

In Koolhaas' Bordeaux Villa, Balmond engineered the rectilinearly but precariously cantilevering boxes and beams that seem to upend Modernism and its midwife, gravity. In Toyo Ito's Serpentine Pavilion, in London, Balmond engineered a taut building envelope seemingly made up only of thin white lines and a few pointy shards of infill between them.

In a video clip shown in the Carnegie installation, Balmond produces a quick 3-D model of the seemingly complex pavilion with a few deft strokes of his Sharpie, followed by a few well-placed folds in the paper surface. Enumerating how Balmond contributes to the conception of a building, Jencks says, "he is part designer, part catalyst, part the unseen hand behind the structure."

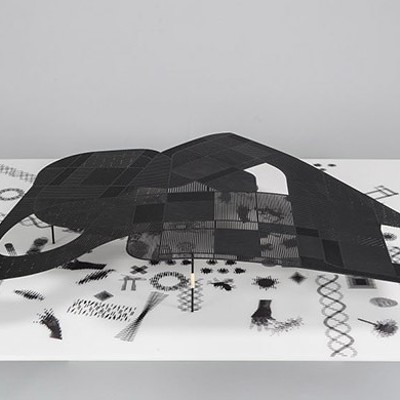

The primary component of Balmond's installation at the Carnegie is an enveloping spatial environment made entirely of 6,000 X-shaped (not really H-shaped) pieces of aluminum sheet metal, about eight inches square, and the vertical chains into which their outer points are ingeniously stuck. The eye wants the chains to be slack, but they become stiff, stretched taut by the arms of the X. From these two simple components, an entire structural system emerges, which can rise to significant heights and span distances enough to create a maze-like spatial composition. It spills out into the main hall of the museum at knee level, inviting visitors into the smaller Forum Gallery, where it becomes more circuitous, layered and enveloping, never losing its strange, anti-gravitational sensibility.

The exhibit also includes a series of six illuminated panels, which aim to encapsulate Balmond's career and principles through a series of thematically linked diagrams, projects, historical precedents and, in some of them, videos. These are labeled with Balmond's slightly oracular epigrams -- "The science of pattern is the poetics of mathematics" -- but they could more concisely be titled Number, Shape, Pattern, Emergence, Time and Equilibrium. These panels are informative, especially with the lucid and professorial Balmond sketching away in the videos, but they seem simultaneously too dense with information and incomplete. What projects has he worked on?

The installation itself, with its visually foliate qualities growing from an astonishingly concise pair of ingredients, derives from the theme of emergence, a favorite theoretical basis for generating utterly complex shapes from biological and digital sources in contemporary architecture. Explains Balmond in that panel, "Emergence is the will of chaotic systems to reach stability."

Actually, H_Edge seems to embody principles of emergence much less than the compellingingly spiraling diagrams shown on the panel. The installation's uncompromising rectilinearity is picturesque without ever losing its essential clarity. This hardly seems to matter. Balmond generates in rapid succession complexities that lesser designers might accomplish after years of study. His persistent claim is that the origins are all to be found in nature's geometry. Clearly, though, it takes a singular mind to bring them into the world.

Cecil Balmond speaks at 3:30 p.m. Sat., Feb. 6 (free; reception follows). Balmond's H_Edge is displayed through May 30. Carnegie Museum of Art, 4400 Forbes Ave., Oakland. 412-622-3131 or www.cmoa.org