Just as there are great books everyone should read, so are there classic films. It's easy enough to get schooled on the popular Hollywood fare, but what of the more obscure and foreign films that once defined a new genre? Starting on Fri., Sept. 21, Pittsburgh Filmmakers presents a two-week film festival, Essential Arthouse: 50 Years of Janus Films, featuring 16 films that offer a primer on what came to be known as "arthouse cinema."

Primarily European films shot during the post-war decades, arthouse cinema was defined by its use of experimental film techniques, allegorical subject matter, enigmatic endings, the decidedly non-Hollywood portrayal of personal relationships and -- let's not forget -- the once-titillating display of nudity and frank sexuality. Here, in the U.S., many of these films also bore the mark of their distributor, Janus Films.

Ingmar Bergman, François Truffaut, Akira Kurosawa and Luis Buñuel were among the directors who, via the U.S. arthouse circuit (located primarily in larger coastal cities and college towns) rose to prominence. Indeed, during the 1960s, no self-respecting tweedy intellectual or philosophy student could be remiss in catching -- and then discussing -- the latest soul-searcher from overseas. But also among the devotees were a new generation of domestic filmmakers, such as Francis Ford Coppola, William Friedkin, Martin Scorsese and Robert Altman, who, suitably enriched, would help re-define and broaden American film in late 1960s and early '70s.

While Filmmakers' selection includes some familiar titles, most of these films -- Buñuel's Viridiana, Dreyer's Day of Wrath and Bresson's Pickpocket among them -- have not appeared on local screens in at least a decade. Yet the impact of these films stretches deep into today's visual media, whether it's America's continued embrace of foreign cinema, its burgeoning indie scene, arty music videos or even a particularly stylish, and nonlinear, television series. Don't miss this rare opportunity to see -- or revisit -- these classics, all in new 35 mm prints, in the theater -- the hushed, dark reverential venue they deserve.

The films screen Fri, Sept. 21, through Oct. 4, at the Regent Square Theater (1035 S. Braddock Ave., Edgewood); the Harris Theater (809 Liberty Ave., Downtown); and Melwood Screening Room (477 Melwood Ave., N. Oakland). Call 412-682-4111 or see www.pghfilmmakers.org for more information. The following are the first week's films.

CLÉO FROM 5 TO 7. The absorbing Agnes Varda, the Mother of the New Wave, tells a story, in real time, of a woman waiting to learn whether she's dying of cancer. Cléo is a popular singer, politically indifferent and thoroughly self-absorbed: Her real sickness is spiritual, caused by the virus of frivolity. As she wanders around Paris, she begins to diagnose herself, pondering her passivity and her belief in fate. (The opening, with a fortune-teller, is the only color sequence.) Released in 1961, this is the first woman-centric New Wave film -- even Cléo's fearless cabbie is a woman -- and Varda takes on her male contemporaries and their fickle females with a derisive portrait of a worst-case scenario. ("As long as I'm beautiful, I'm alive," Cléo tells a mirror.) The scenes of Paris and Parisians are stunning, and Varda's inventive camera work is cool or energetic as it needs to be. Watch for cameos by Godard and by Michel Legrand, who composed the score. In French, with subtitles. 8 p.m. Fri., Sept. 21; 5 p.m. Sat. Sept. 22; and 4 p.m. Sun., Sept. 23. Melwood (Harry Kloman)

DAY OF WRATH. The story's a little Crucible and a little Scarlet Letter: In the midst of a 17th-century witch-hunt, Danish village minister Absolon's much younger wife, Anne, begins an affair with his adult son. Anne's own mother, we learn, was an accused witch, whom Absolon saved, claiming the daughter. Yet in this astounding and little-seen 1943 drama (filmed during Nazi occupation), any hint of melodrama dissolves at the singular touch of Carl Theodor Dreyer: His films are like no one else's, not least in the majesty of the deceptively simple camera movements. Meanwhile, the moral complexities his characters embody are as tangled as the drama itself is intensely realized. Day of Wrath isn't about witches or adultery (or even necessarily about Nazis). Even so far as it maps the evils of religious orthodoxy, it's more concerned with the inescapable thicket of anguish that both desire and repression can make of the human heart. In Danish, with subtitles. 7 p.m. Fri., Sept. 21; 4:30 p.m. Sat., Sept. 22; and 8 p.m. Sun., Sept. 23. Regent Square (Bill O'Driscoll)

DEATH OF A CYCLIST. Juan Antonio Bardem's taut, moody 1955 drama is a psychological crime-and-love thriller that owes its style to the burgeoning Italian realists as well as to such assured stylists as Alfred Hitchcock. The crisp black-and-white film is brilliantly edited, and features a haunting score. In Death, a couple in a car hit a cyclist, opting to leave the injured man to his death rather than reveal their affair. The incident serves to expose social and philosophical fault lines between the lovers. The politically active (and frequently jailed) Bardem takes clear shots at the Franco regime, class inequity and even the nepotism that helped perpetuate the closed circle of the bourgeoisie, while nodding to the lost glories of the civil war and the hope of a new generation of dissenters. Upon its released in Spain, this existential character-study-cum-stinging-social-rebuke was censured as "gravely dangerous." Today we may be more inured to "immoral" behavior, but a chill runs through Death that's hard to shake, even with its Franco-fied "acceptable" conclusion. In Spanish, with subtitles. 9:30 p.m. Fri., Sept. 21; 9 p.m. Sat., Sept. 22; and 6 p.m. Sun., Sept. 23. Regent Square (AH)

JULES AND JIM. François Truffaut's immeasurably sad 1962 film is difficult to watch a second or third time, so painful is its fatal romanticism. Based on a novel, it's still uniquely Truffaut, vivid with the breathless energy of the emerging New Wave, but in the end, as still and beautiful as a mountain lake. Is art the work of the artist, or a convergence of divine accidents? Midway through Jules and Jim, the "poisoned kiss" begs the question. And how could someone like Jeanne Moreau just happen? As Catherine, the center of the film's love triangle between the eponymous friends, she's literally cast in stone, an icon even before we see her in the flesh. Her unforgettable rendition of the lively-cum-bittersweet "Le Tourbillion" ("the whirlwind") remains an elegy to an impossible dream, and its instrumental reprise at the end is devastating, the final knife in the heart. In French, with subtitles. 8 p.m. nightly, Tue., Sept. 25, through Thu., Sept. 27. Regent Square (HK)

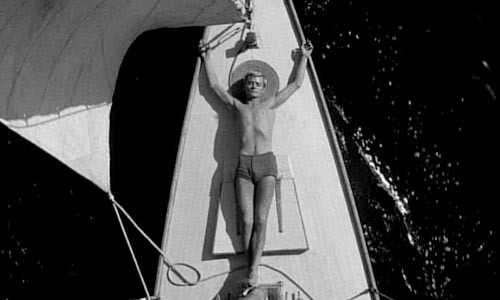

KNIFE IN THE WATER. Imagine if all film debuts were as beautifully filmed, meticulously constructed and psychologically intense as this, Roman Polanski's first feature, produced in 1962. A married couple pick up a young hitchhiker and include him in their overnight sailing trip; three on a boat proves incendiary as the two men -- the arrogant older husband and the handsome naïve loner -- spar for the bemused woman's attention, with inevitable (yet surprising) troubling consequences. Polanski effectively conjures sexual tension and simmering violence (enough to make viewers squirm). Much of that unease is generated during lengthy sequences where seemingly nothing of import happens: the marking of the ever-changing weather, and languid throwaways of the boaters bathing. The dialogue is spare, with body language often most telling. And throughout, Knife is breathtakingly gorgeous -- shot in high-contrast black and white, with exquisite framing and camerawork. In Polish, with subtitles. 7:30 p.m. nightly, Mon., Sept. 24, through Thu., Sept. 27. Harris (AH)

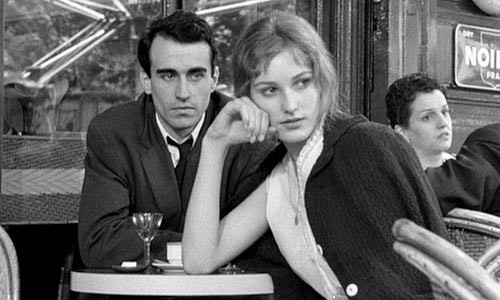

PICKPOCKET. Among the great directors of European cinema, few get less U.S. exposure than Robert Bresson. Typically, that's attributed to the austerity of his vision -- stark imagery, nonprofessional actors, stripped-down stories. But this 1959 drama suggests it might also have to do with the ambiguities inherent in his approach. As critic Gary Indiana has noted, this Crime and Punishment-style story -- small-time crook Michel's transgressions are the source of his redemption via imprisonment -- can seem unconvincing even to Bresson himself. Society's crimes of mass indifference appear to dwarf Michel's penny-ante law-breaking and lukewarm speeches about Nietzschean supermen; meanwhile, his relationship with a lonely young woman dwindles compared to his almost erotic encounters with the master pickpocket who schools him. Interpret as you will, you'll see nothing else like it this year. In French, with subtitles. 7 p.m. Sat., Sept. 22; 4:15 p.m. Sun., Sept. 23; and 8 p.m. Mon., Sept. 24. Regent Square (BO)

SEVEN SAMURAI. Villagers hire mercenaries to protect them from raiders, but Akira Kurosawa's 1954 masterpiece is far more than just another action epic. The samurai hirees are a down-on-their-luck bunch, already suffering obsolescence as a class in this 16th-century setting — a condition they share with the putative bad guys, themselves erstwhile samurai. The victimized villagers, meanwhile, aren't so utterly sympathetic as they might first appear, and not just because they can't swing swords. It's a series of layers commenting on social class, warfare and valor that intersect in the person of Toshiro Mifune's wannabe warrior, who starts out as comic relief for Takashi Shimura's reflective head samurai and ends up the soul of this film, whose dramatic arc is every bit as engrossing as its thrilling formal beauty. In Japanese, with subtitles. 7:30 p.m. Fri., Sat. Sept. 21; 7:30 p.m. Sat., Sept. 22; and 3 p.m. Sun., Sept. 23. Harris (BO)

VIRIDIANA. Luis Buñuel, the expatriate Spanish surrealist who may or may not have said "Thank God I'm an atheist," returned to his native Spain in 1961 to make this sardonic rout of religious hypocrisy -- and promptly got thrown out again. It's the story of a newly minted nun, the uncle who rapes her, and the cousin who seduces her into a ménage-á-trois. It's one of Buñuel's four or five masterpieces, at once intellectual, antithetical and perversely funny: He poses the beggars, whom Viridiana tries to help, as "The Last Supper," and then has their photo taken, in the words of the bawdy photographer as she lifts her dress, "with the camera my daddy gave me." Buñuel has little to say about God per se, but much to say about organized religion, the anathema that drove his artistic vision. It presents a dark view of human nature, and it unequivocally says (spoiler alert) that we'll all play cards some day. In Spanish, with subtitles. 7 p.m. Sat., Sept. 22; 2 p.m. Sun., Sept. 23; and 7:30 p.m. Mon., Sept. 24. Melwood (HK)