A woman sits on the floor, clothed in purple and blue, accentuated by turquoise jewelry and glinting rings. She is draped baroquely over a laptop computer, one hand holding her chin as she peers into its screen.

The Ballardian scene, a pastiche of romanticism and technological reliance, seems appropriate for the Pittsburgh Technology Center's 15 Minutes Gallery -- and certainly for a show entitled Art, Man and Technology.

But it's not in the show. It's a moment from the opening reception.

Artist Steve Kilbey attended his opening via Skype, interacting with guests by computer from his home in Australia. The woman, a devoted fan of Kilbey, took the chance to clear up some elements of his art for him: "Well, that's because you're a Virgo," she explained to Kilbey's on-screen image.

As the lead vocalist, bassist and co-songwriter for Australian cult psychedelic-rock band The Church, Kilbey gained international fame for 1988's MTV hit "Under the Milky Way." But to his fans, The Church's three-decade stream of glittering guitars and esoterically spiritual lyrics makes him less one-hit wonder, more paisley-shirted prophet. So despite having launched his professional art career only three years ago, Kilbey begins with a heady fanbase, a vast amount of cultish Internet chatter, and a lot of artistic baggage.

The 19 paintings in Art, Man and Technology exhibit the same post-hippie, drug-addled futurism -- let's call it "psy-fi" -- as Kilbey's music. In fact, for each painting, Kilbey has created an audio track, played on a portable CD player. The new music won't surprise fans: droning, buzzing guitars and psychedelic washes of voice-like synthesizers create a minimalist bed for his spoken-word pieces.

Sometimes, those poems add a lot. In "The Appearance of Life," a Lascaux-esque cave painting of swirling fox-like shapes, the audio helps imagine a new myth that holds science and spirituality as equals. ("If God won't appear in your test tube / does that mean he doesn't exist?")

Other paintings, however, gain nothing from their soundtracks, particularly the portraits. We can hope that Kilbey is being crassly tongue-in-cheek when he says, on the track for "Ben Frank," that he began painting this C-note-on-acid because he thought it was William Penn, and "that'll get 'em going, those guys in Pittsburgh, PA." But it's even more of a stretch to hope that "Finally, a Good Guy," a beatification of Barack Obama that would make the most gushing fan blush, itself comments on media adoration.

Yet despite its multimedia pretenses, what's most interesting about Art, Man and Technology are the paintings themselves.

Kilbey is the first to admit -- nay, proclaim -- that he has "10,000 influences as a musician, but as an artist, I have none. I have no idea where it comes from." Yet perhaps it's in that untutored gaze that we most clearly see influence -- one saved from contemporary art's rhetorical bearing and shedding of reference.

The best paintings here reveal influences that, like Kilbey himself, originate outside the academy: New-age spirituality and conspiracy theory, Aboriginal Australian art and mythology, and other "outsider" art brut. (Kilbey denies knowledge even of the indigenous artwork, admitting only that "there's a lot of it in the shops that I pass by.")

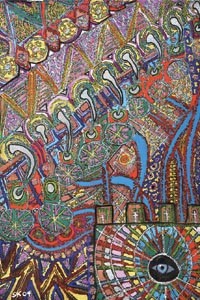

Still, "The Great Machine" might be straight out of Baltimore's American Visionary Art Museum, a chaotic jumble of colors and shapes (wheels, eyes, bone, crosses) like a drug-fueled stained-glass window. Accompanied by a track of rhythmic breathing and Kilbey's "reverie," it becomes an examination of hegemony: "[W]e are its raw material / we are its end product." Similarly, "The Lonely City" might be a darker, rawer John Kane cityscape, with its instinctive, rather than scientific, perspective.

The best half-dozen paintings reference the people and practices left behind and denied by the intersection of man and technology. Technology, it suggests, is a destroyer of worlds -- dream worlds and mythological ones like Lemuria, the Pacific version of the Atlantis "lost continent" myth, which Kilbey references constantly.

Outsider art, on the other hand, has always been a creator of worlds -- be it Henry Darger's Vivian Girls, or the built environments of Howard Finster. It's not hard to decipher which side Kilbey is on. As communications technology makes it harder and harder to imagine the unknowable, the fringes of our cultures grow more and more interested in cryptozoology, crop circles and lost continents. We cling to our myths even as we kill them off.

Art, Man and Technology is an interesting look at an artist beginning to fuse multimedia and traditional painting. Moreover, Kilbey's name is internationally acclaimed, in music if not art. For 15 Minutes Gallery to host his first-ever major solo gallery show will surely solidify the space's place in the city's cultural landscape.

Art, Man and Technology continues through June 1. 15 Minutes Gallery (Pittsburgh Technology Center), 2000 Technology Drive (off Second Avenue), South Oakland. 412-687-2700.