A cresting '90s revival requires proper tribute to riot grrrl — the hybrid underground movement that reimagined punk rock's DIY modes with feminist purpose. Typically, riot grrrl's legacy is told through music, but Alien She, at Carnegie Mellon's Miller Gallery, offers a spirited collection — part art exhibition, part historical project — showcasing the movement's artifacts while honoring its evolved second life in art in various media and disciplines. (This reviewer, though employed by Carnegie Mellon University, is unaffiliated with the Miller Gallery).

The first major exhibition dedicated to riot grrrl, Alien She is both instructive-ly designed and loyal. That's unsurprising: Curators Astria Suparak and Ceci Moss were involved in the West Coast-bred scene as teens. "The participants of the original movement were in their teens and 20s in the '90s, and have since solidified their identities, interests and careers," writes Suparak, director of the Miller Gallery, in an email. Alien She includes works by seven artists who, she writes, "have incorporated, expanded upon, or reacted to riot grrrl's ideology, tactics and aesthetics."

As a gateway, the gallery's first floor is dedicated to riot grrrl's creative output, including hundreds of self-published zines, fliers and more, gathered from personal and institutional collections. Neatly arranged rows of paper trace a retired analog past — the Xerox-and-Sharpie, feminine brute universe of the riot grrrl — now brushed off for the archives. Learn something or get nostalgic, but save energy for the artworks on the second floor.

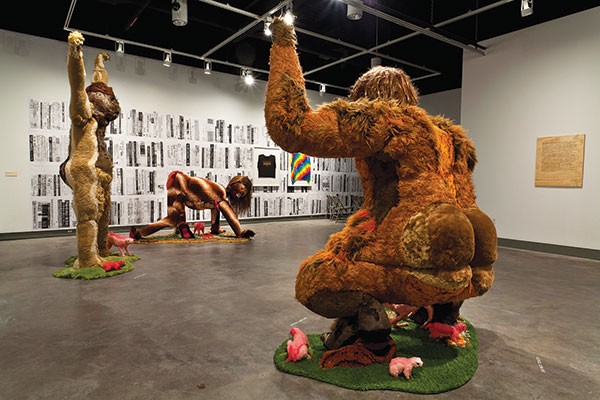

Breaking the ice are Allyson Mitchell's three towering hominids in estrus — suitably titled "Ladies Sasquatch" — whose burly-girly displays (what are they to do with no male in sight?) are betrayed by their craft-kitsch construction: a repurposing of granny's fabric scraps and wigs? A discarded teddy-bear collection? Neighboring this joyous barbarism is Mitchell's sly tribute to academic feminism, with a wall-sized pencil drawing depicting a robust feminist library framing a diptych of T-shirts reading: "Women's Studies Professors Have Class Privilege" and "I'm with problematic." The grouping suggests that feminism is caught in a nauseating feedback loop.

A counterpoint are Tammy Rae Carland's large photographs that pause overthinking. These include the romantic, slept-in colorfields of "Lesbian Beds," while the empty stages in "I'm Dying Up in Here" evoke awkward stillness, as if the performer had just fled the scene. Carland talks love, anxiety, attachment and queer politics without bristles.

There's also a career-spanning collection by filmmaker, performer and author Miranda July. A sure highlight is her video "Nest of Tens." It's worth the 10 minutes — rarely will you find such provocative, sometimes difficult, push and pull about gender, sex and class in such a deceptively banal narrative.

The third floor further reconciles art and post-riot grrrl acolytes, starting with L.J. Roberts' crowd-pleasing, 15-foot-tall barbed-wire fence encased in fuchsia yarn and titled, "We Couldn't Get In. We Couldn't Get Out" — an impressively belabored sculptural trope. Roberts' other works borrow from the visual language of protest, including a giant flag, originally installed on a church steeple, reading "Mom Knows Now," which wall text characterizes as "a coming out and a declaration."

Stephanie Syjuco's brainiac installations mark the intersection of sociocultural provocation and dry humor. "The Counterfeit Crochet Project (Critique of a Political Economy)" is a participatory work, inviting viewers to crochet knockoffs from a catalog of hacked patterns, from Gucci purses to Burberry scarves. Syjuco's visually tame projects give me a thrill: An affable troublemaker has officially infiltrated the system.

Riot grrrl found empowerment through its marginality as a radical movement, a sensibility distinct in works by Ginger Brooks Takahashi. She's a founding member of feminist genderqueer art collective LTTR (which formerly stood for "Lesbians to the Rescue"). "A Wave of New Rage Thinking," reads a post-apocalyptic-looking piece of signage tacked to the wall that Twitterizes the first floor's famous riot-grrrl manifesto. "Feminist Body Pillow" is a fleshy dog-pile of stuffed T-shirts printed with racy though delicate assertions of lesbian lust and queer visibility.

Also featured is Brooks Takahashi's traveling Projet Mobilivre-Bookmobile Project, "an effort to bring artists' publications to a wider audience while demystifying bookmaking with workshops." Altogether, Brooks Takahashi uncovers feminism's tendency to vacillate between friendly separatism and determined community-building.

Community-building, a withstanding preoccupation among feminists and artists, is central to Faythe Levine's photographic series "Time Outside of Time," which documents off-the-grid communities.

Alien She is superbly designed, comprehensive and approachable. But it's important to remember that riot grrrl was anti-authoritarian, gritty, screechy. It reveled in failure and was intentionally unsuitable for mass consumption. One wonders whether institutional sanctioning of such movements is the compromise required to get them into history books. If so, perhaps it's OK, because this exhibition's authors were directly involved with the movement. Nonetheless, Alien She resounds riot grrrl's, and feminism's, hold on contemporary life. It says, "This happened, keep going."