At a June meeting, dozens of residents showed up to hear updates on a city proposal that would ferry autonomous shuttles through Oakland, Greenfield, and Hazelwood. By and large, residents were skeptical of the autonomous-vehicle proposal. Several of them sported buttons reading, “Not Sold on AV.”

Public-transit advocates think the city’s money and effort would be better spent procuring additional bus service from Hazelwood, and that the small shuttles can’t adequately serve the growth that the city is hoping to see in the corridor.

But the city believes the project, called the Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC), can provide an improved and important transit connection between its two largest universities and the growing tech industry. Leaders also see a chance to help boost development in this corridor and make upgrades to provide flood relief.

In theory, the MOC seems like a project that would easily garner support: a “cool factor” for using shuttles that can drive themselves, adding transit between neighborhoods that don’t currently have adequate service, and a pot sweetener of a stormwater-infrastructure upgrade long requested by residents.

So why are so few people getting onboard?

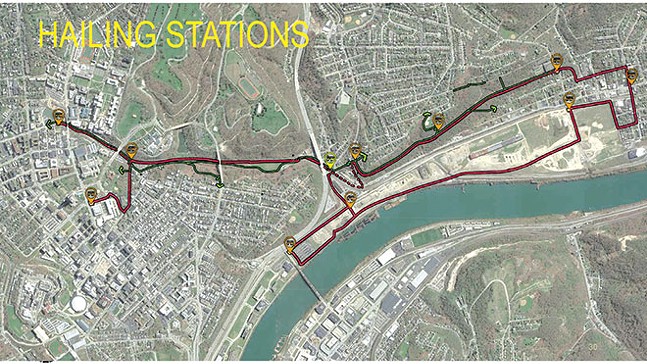

Residents in Four Mile Run, the Greenfield neighborhood that would be in the middle of the shuttle route, just don’t believe the project will better their neighborhood. The MOC would run autonomous shuttles carrying about 12 people per shuttle on about a 5-mile loop with 12 transit stops, where users would hail shuttles on-demand. The city is expecting the Mon-Oakland Connector will cost between $14-17 million of city funds to complete. Autonomous shuttles implemented in other cities have traveled an average of about 15 mph.

Ziggy Edwards of Four Mile Run says the MOC isn’t for locals in Greenfield and Hazelwood, but rather geared at Carnegie Mellon University and University of Pittsburgh students and workers looking for a better connection to the new tech-centric development at Hazelwood Green. Edwards thinks the MOC isn’t about improving her neighborhood, noting the project has always been a goal of CMU and Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto, regardless of resident input.

A 2009 paper entitled “Remaking Hazelwood” from CMU’s School of Architecture proposed a light-rail line to run through Junction Hollow and up to Oakland and beyond. Back in 2009, Peduto, then a Pittsburgh City Councilor, also supported the creation of a light-rail line from Hazelwood through Oakland and on into Lawrenceville. Like many transit proposals in Pittsburgh’s history, neither came to fruition.

Then in 2015, the federal government was offering $50 million to the city that could incorporate autonomous vehicles into a public-transit proposal. This time, CMU and the city, now with Peduto as mayor, teamed up and pitched a transit line from Oakland to what is now called Hazelwood Green, whose first tenant happens to be CMU. Four Mile Run residents were opposed to that pitch, too. The federal grant eventually went to Columbus.

Edwards says if city leaders were focused on the mobility of area residents, as they have said at many community meetings, they would be repairing sidewalks along Irvine Street and improving bike-trail connections to Hazelwood, and would be less concerned of potential development impacts of a shuttle route.

“They are uninterested in any other solution because it allows them to control land from the edge of Oakland all the way through the Junction Hollow valley and Hazelwood to the banks of the Monongahela,” says Edwards.

Karina Ricks, director of Pittsburgh Department of Mobility and Infrastructure, says encouraging development is, and should be, part of the reason to create the MOC.

“Putting vacant land back into productive use is a good thing to increase city resources for reinvestment [in these] communities,” says Ricks. “Mobility and access most definitely influence the success of regeneration efforts.”

But development doesn’t always follow new transit lines, especially ones that are slow and low-capacity. A 2018 study from San Jose State University analyzed the effect of streetcars — vehicles that run along fixed routes, for relatively short distances, and at low speeds, similar to the proposals of the MOC — on its environment. The study concluded that streetcars had a questionable, and sometimes negligible, impact on development.

While many organized residents like Edwards are critical of MOC’s priorities, some are just completely against the idea of added transit in their area.

“They don’t want it; they don’t need it,” Four Mile Run resident Klaus Libertus told PublicSource in 2018. “We are more concerned about keeping a quiet neighborhood where our kids can play safely and walk across the street.”

But adding public-transit connections to neighborhoods can have positive effects, such as combating poverty. A recent study from Cleveland State University found Cleveland neighborhoods that gained transit access saw poverty rates fall and overall employment numbers increase. The Greenfield census tract that includes Four Mile Run doesn’t have significant problems with high poverty rates, but Hazelwood has poverty rates significantly higher than the Allegheny County average of 12.5 percent.

Ricks says improving the inadequate public-transit access from Hazelwood to the high concentration of jobs in Oakland and is a driving factor behind this project. The current bus from Hazelwood to Oakland, the 93, takes about 30 minutes on a meandering route, despite the two neighborhoods only being about three miles apart.

“This appears to be a mismatch,” says Ricks. “We know that travel time is, according to research, the single greatest factor in people being able to access, take [transit], and rise above unemployment to better their life outcomes.”

In terms of safety, other low-speed autonomous shuttle programs have yet to experience any issues. Las Vegas has been running an autonomous shuttle on a half-mile loop for over a year without incident. Officials in Arlington, Texas piloted an autonomous shuttle project in 2018. Arlington planner Ann Foss says the pilot had successes, like how virtually everyone was comfortable riding in the autonomous shuttles, but also challenges in the functionality of the autonomous technology.

While city officials should be able to calm safety concerns and sell the connector as an anti-poverty tool, public-transit advocates are still skeptical the shuttles will be effective.

Laura Wiens of Pittsburghers for Public Transit says the proposed vehicles are too slow and low-capacity to service the potentially more than 100,000 jobs that would exist in that corridor. Pittsburgh’s projections for initial ridership of the shuttle to be about 1,200 people, which Wiens says is also overly generous.

“In terms of capital investments, let's start with what we know works and things that can carry people in bigger quantities,” said Wiens at a May rally against the MOC. “We don’t think the shuttles will be adequate.”

Foss says the Arlington pilot showed some potential hiccups of autonomous shuttles. She says her department had to install birdhouses and tall poles along the route, and trimmed trees and other vegetation to ensure a clear path so the shuttles wouldn’t automatically stop. Large rocks also had to be installed on the trail for the safety lasers to see in case the vehicles drifted off the path.Wiens believes the city should be bettering mobility by channeling funds to Port Authority of Allegheny County to expand the 93 bus service, which doesn’t run on the weekends, and focusing on a potential Bus Rapid Transit route running along on Second Avenue in South Oakland.

Foss says Arlington’s experience with autonomous shuttles showed her they are “best suited for shorter distances” and first/last mile connections. “A larger vehicle with more passenger capacity and higher speeds would likely be necessary for a larger scale deployment,” says Foss.

Wiens says the city’s sell so far feels “pro forma” and officials already have their minds made up that the MOC is best for transit. She also thinks officials keep moving the goalposts, including offering a Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority collaboration to mitigate stormwater issues, and saying at the last public meeting that the shuttle routes will also be used for personal electric-assist bikes and scooters.

“They have identified that they want this experimental technology deployed and then will figure out later how it can be sold to the residents,” says Wiens.

Convincing people of the MOC’s virtues has been such a failure so far that the city sought and acquired a $400,000 grant from the Knight Foundation for outreach on the project.

But Ricks says the MOC is necessary so development and growth can continue in the Oakland-Hazelwood corridor without adding too many cars. “What we do not want is urban infill that is heavily oriented around private vehicle use,” says Ricks. “To avoid that we must enhance travel alternatives. Providing this one little mobility link can increase transit use on existing lines as well.”