Kelley Kelley was honest with voters when she campaigned three years ago for mayor of Turtle Creek, a Rust Belt town about 12 miles southeast of Pittsburgh.

She told them her husband, Kevin, is a recovering heroin addict who was arrested nine years ago for a nonviolent crime. She said proper treatment, not jail time, saved his life and their marriage. And she promised that, if elected, she’d take an empathetic approach to ease the pain heroin has inflicted on her hometown.

“You can make all the arrests you want, it’s not going to solve the problem,” says Kelley, 42, who this year will complete classes to become a certified substance-abuse counselor. “It needs to start in every home, and it’s a discussion they need to start having.”

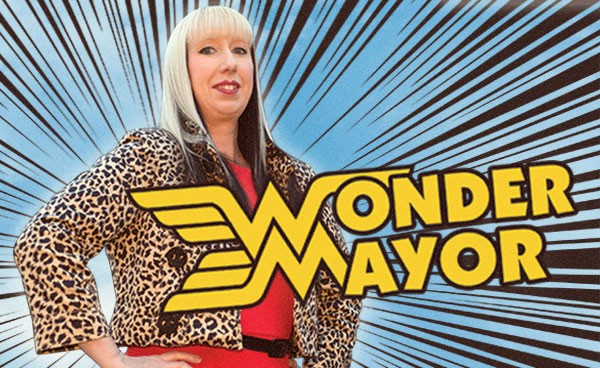

She was elected mayor in 2014, and then came the hard part. Emergency responders reported a spike in the number of heroin and prescription-opioid overdoses that year in Turtle Creek, a town of about 5,000 with an average household income of $31,000. Drawing from a master’s degree in criminology, her experience with a local advocacy group and her fandom for Wonder Woman — who stands with hands on hips on a shelf in her office — Kelley took a three-pronged approach to buck the trend.

— Train police officers to educate nonviolent offenders who have an opioid addiction about nearby treatment options at the time of arrest.

— Provide affordable treatment options in and around Turtle Creek and teach residents how to prevent a fatal overdose.

— Empower residents to report suspected drug activity outside their homes, anonymously if need be.

The plan might already be working.

Emergency responders who serve Turtle Creek reported nine heroin- and prescription-opioid-related overdoses in 2015, after an average of 14 overdoses each of the previous four years. This while heroin-related deaths throughout Allegheny County increased for the fifth consecutive year in 2015.

“[Kelley] is educating people on the disease, and she’s providing tools not just for police, but for everyone,” says recently elected Turtle Creek Borough Councilor Connie Tinsley, who also has taken classes to become a substance-abuse counselor.

Enforcement vs. Education

One of the first officers Kelley helped hire was Joe Wincko, whose childhood friend died in 2014 of a heroin overdose. Wincko was in the police academy when he received the news.

“This guy was pretty much like a brother to me, and it crushed me,” he says.

The fatal batch was laced with fentanyl, which the Allegheny County coroner linked to 14 other deaths in January of that year.

“At first, I was upset with him, which turned into trying to seek knowledge,” Wincko says. “I wanted to know why he did it and [what] the addictive properties are in heroin. I wanted to know the right steps for someone on the road to recovery and how to get them there.”

In light of what the Centers for Disease Control has deemed an epidemic in the U.S., officers in Turtle Creek have taken on a new role as educators, police chief Dale Kraeer says. They’re trained to speak with nonviolent offenders who show signs of addiction, and their family members, about inpatient and outpatient detox and counseling in the area. He said the end game, from a law-enforcement standpoint, is to reduce the number of thefts, robberies and burglaries fueled by addiction.

“If you’re a victim of drugs, you’re capable of all kinds of crime,” Kraeer says.

The word “victim” is indicative of a paradigm shift among law enforcement throughout the U.S. as the rate of heroin-related overdose deaths nearly quadrupled from 2002 to 2013.

A program spearheaded in June by the police chief of Gloucester, Mass., linked 150 people with free treatment, in lieu of arrest, within the first three months of its inception. People traveled to the police station from out of state for treatment.

And as an increasing number of state and city leaders have voted to reform marijuana laws, the war on drugs has started to become a war on heroin.

In August, the White House announced an initiative that paired drug intelligence officers with public-health coordinators to trace heroin from port cities, such as those in New York and New Jersey, with a special interest in batches laced with a deadly additive. Federal and local law-enforcement officers in retail-heavy Monroeville, which borders Turtle Creek, have pointed to such port cities as the starting point for millions of dollars worth of heroin transported to the east suburbs over the last five years.