When the defendant walked into U.S. District Court Judge Maurice Cohill's courtroom for sentencing early this month, he was facing a prison sentence that could last as long as 20 years. The crime: conspiracy to distribute, and possession with intent to distribute, more than 5 kilograms of cocaine.

"I'd like to apologize for even being here in court," said the defendant, whose own parents struggled with drug addiction. "I was trying to break the cycle, and now it's like the cycle is going to keep going."

But Cohill took a step to prevent that cycle from spiraling downward any further than it had to. The accused had experience running his own (legal) business, he noted, and had brought a half-dozen supporters with him to the hearing. "[Your history] adds up to someone who shouldn't have been in legal trouble at all," Cohill said. Taking that background and other factors into account, Cohill handed down a sentence of just eight years.

That kind of flexibility has become more common since 2005, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that once-ironclad federal sentencing guidelines are no longer mandatory, and should be considered advisory instead. And critics of the criminal-justice system — especially its handling of drug cases — say progress is being made, though more needs to be done.

For one thing, says Angus Lowe of the Pennsylvania Institutional Law Project, "We have a reasonable President who sees we can no longer afford to expand the prison system. And the best way to [fix] that is to reduce the number of non-violent drug offenders in prison."

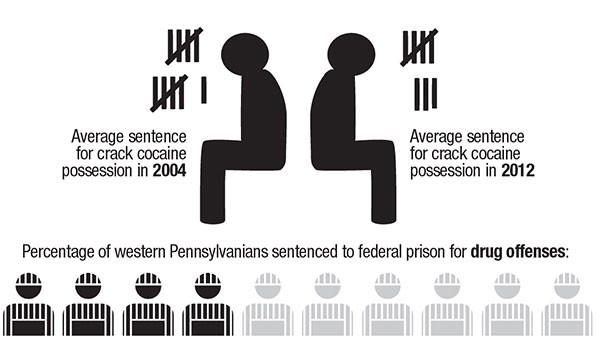

Drug offenses still clog courtrooms in western Pennsylvania's federal courts. According to the U.S. Sentencing Commission, drug trafficking made up 35 percent of all cases tried here in 2012 — more than any other kind of offense.

But the 2005 Supreme Court decision United States vs. Booker allowed judges to hand down sentences below federal guidelines, and today they frequently do so: 45 percent of western Pennsylvania offenders that come before federal judges received sentences below the guideline range.

But some critics say those numbers veil ongoing problems.

Judges can depart from mandatory minimums — which set a base-level prison time — and other sentencing guidelines for a few reasons. Among them: cooperating with the government and pleading guilty. The latter is especially common. In western Pennsylvania, 96.9 percent of all offenders in federal court pled guilty in 2012, according to the U.S. Sentencing Commission. In just over 17 percent of cases, meanwhile, defendants received a lighter sentence by providing law-enforcement with help bringing down other suspects — a trade-off called a "substantial assistance departure."

Some skeptics say that while both rationales can knock years off a sentence, they may create injustices of their own.

"If you can threaten a lot of time, you can pressure people to plead guilty," says David Harris, a University of Pittsburgh law professor. "What they're hearing is, ‘If you don't plead guilty, you're going to face 20 years ... but we can reduce it if you do.'"

Meanwhile, he says, the "substantial assistance" rule does little for foot-soldiers in the drug trade, who may deserve punishment the least. "If I'm a low-level dealer, I might want to give information," Harris says. "But there's no way for me to reduce my sentence because I don't know anything."

Magdeline Jensen, CEO of the YWCA of Greater Pittsburgh agrees. She worked with the U.S. Sentencing Commission when the guidelines were first drafted.

"Offenders who have major involvement have more information," Jensen says. "The people who have a smaller role can get caught up despite the fact they may have no record."

U.S. Attorney David Hickton, who represents the Western District of Pennsylvania, declined comment.

Ironically, perhaps, when the sentencing guidelines were established by the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, the goal was to make sentencing more equitable by reducing disparities from one judge to another.

"The whole point was trying to bring some parity," says Jensen. "The original idea is they get applied and if the court doesn't sentence in the range, [a person] can appeal" rather than be subject to a judge's whim.

But sentencing disparities have remained. A 1994 study published in Federal Sentencing Reporter found that racial disparities in sentencing increased after the guidelines were adopted. A later 2001 analysis by David Mustard, a University of Georgia professor, found that African-Americans received sentences 5.5 months longer than whites.

Reformers say the guidelines aren't solely to blame.

"The racial disparities are present long before sentencing," says Anna Hollis, president of Amachi Pittsburgh, an organization that works with children of incarcerated parents. "The racial disparities begin at the point of policing" — with minorities being arrested more often than whites.

Currently, the momentum has shifted toward reducing penalties across the board for those convicted of drug crimes. On Jan. 30, the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee voted in favor of the Smarter Sentencing Act, which includes provisions for reducing prison sentences for non-violent drug offenses. The legislation would cut mandatory minimum sentences of 20, 10, and 5 years in half for drug crimes, provided they don't result in death or serious bodily injury to others. It would also give judges more flexibility to reduce sentences for offenders who have little or no previous criminal record.

Should the measure come to a full vote, Pennsylvania Democrat Bob Casey says he'll consider it.

"I'm pleased the Senate Judiciary committee is reviewing mandatory minimum sentences and modifying sentencing guidelines for certain drug offenses, which could reduce dangerous overcrowding in federal prisons and save billions of dollars," Casey said in a statement to City Paper. "This is an important step in improving the fairness and effectiveness of our justice system."

The office of Republican Senator Pat Toomey did not respond to questions about his position on the legislation.

While the legislation has support from Democrats and Republicans, as well as U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, it is being criticized by the National Association of Assistant United States Attorneys.

"We need to preserve the current mandatory minimum framework," NAAUSA said in a statement. "Mandatory minimums correspond to the most serious crimes committed by the most dangerous criminals, provide prosecutors the leverage to seek cooperation, establish uniform sentences, and most importantly protect our citizens."

Despite such critics, supporters say the legislation is indicative of shifting attitudes around drug offenses.

In December, President Barack Obama commuted the sentences of eight crack-cocaine offenders. He'd previously signed the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which made the punishments for possessing or distributing crack cocaine more consistent with offenses involving powder cocaine. (Previously, sentences for crack were harsher.) While the 2010 legislation affected only future prosecutions, a provision in the Smarter Sentencing Act would make the new sentences retroactive, shortening sentences for current federal inmates.

Lowe, of the Pennsylvania Institutional Law Project, lauds such changes. One of his clients is serving time on a sentence handed down under the old rules.

"He's still doing 25 years" for selling crack, Lowe says. "Most places you get that for murder. That's ridiculous."

There have been changes at the state level too. In 2012, Gov. Tom Corbett — the state's former attorney general — passed the Criminal Justice Reform Act, which expanded alternative-sentencing opportunities, like electronic monitoring, for nonviolent drug offenders whose crimes were motivated by addiction.

Lowe sees such developments as a sign the nation's war on drugs might be coming to an end.

"The drug war in itself has been a failure," Lowe says. "Drugs are no less available then they were before. People are being locked up, and money is being spent for no gain. It doesn't stop the trade. It just locks a lot of people up."