"At once with joy and fear his heart rebounds."

-- Paradise Lost

There's an odd stillness where Brighton Road meets Davis Avenue at the crest of Brighton Heights. Despite the cars buzzing by, and the streets crowded with row houses, there's no one around on this clear Sunday morning in mid-September.

The intersection is dominated by three large buildings, each painted in a weathered, muted gray like the color of ash. To the right is a long rectangular structure -- a social hall -- with a rectory sitting behind a 20-foot-tall pine tree on the left. The middle building's roof is steep -- the tallest of the three -- and its windows are stained glass, resting on either side of two heavy, wooden doors.

Outside, a small, white, Dry-Erase sign reads "Welcome Recovering Roman Catholics" in handwritten black marker.

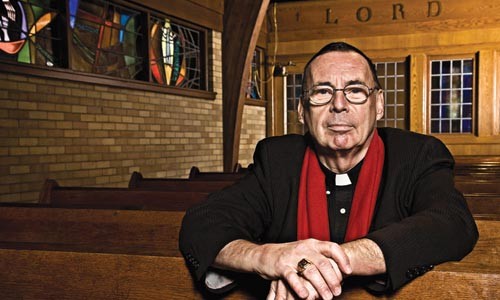

This is the spiritual center for Christ Hope Ecumenical Catholic Church (CHECC), where a group of two dozen attends to the words of pastor C. William Hausen -- known to the faithful as "Father Bill or "FB."

The service has reached one of the rituals that separates CHECC from the Roman Catholic Mass it generally resembles. After the homily -- the part of the service where the priest expands on the day's Bible readings -- discussion is opened to congregants. Often, the parishioners share news of sick or dying loved ones, and exchange words of comfort. Today, though, a large bald man named Ned -- who is in his early 30s and by far the youngest person at the gathering -- stands and speaks.

Ned is bothered by Matthew 18:17, where Jesus discusses the method of settling disputes within a church community. If all attempts at mediating the argument fail, Jesus counsels, believers should treat those they disagree with "as you would a Gentile or tax collector."

What does that mean? Ned asks Hausen, who stands before the congregation in a white, unadorned vestment. How exactly does one treat a Gentile or tax collector?

After a moment of contemplation, Hausen smiles. "Some of the gospels are filled with commentary that's no longer relevant," he says.

Ned's response is quiet, yet concerned. "But where does that leave us?"

For Hausen, 70, it has left him cast out from the church he grew up in.

It's a surprising fate for someone like Hausen, who was born in 1938 and grew up as one of four children in a staunchly Catholic Shadyside household.

"When I was a kid, everything was geared toward the church," he says. "If you wanted to become a priest, all of a sudden you became important."

Hausen went to Sacred Heart Grade School and Central Catholic High School. And he says he recalls getting special treatment from his teachers -- to the point, he says, that he was put on the honor roll simply because he showed interest in the priesthood.

"I was being supported -- propped up, even -- by the church," he remembers. "Everyone told me what to think. It was always spelled out: that you were a better person if you were celibate. And, not to be narcissistic, but you had the best and the brightest headed into seminary. So that's where I wanted to go."

In 1956, Hausen attended St. Charles Borromeo Seminary, just northwest of Philadelphia. After studying there for nine years, he was ordained as a priest and returned to the Diocese of Pittsburgh. There, he ministered to congregations throughout the diocese: Brookline's St. Pius X, St. John the Baptist in Plum, his childhood parish of Sacred Heart in Shadyside. Amidst it all, he took graduate classes in theology and psychology at Duquesne University.

"I loved what I was doing," he remembers. "I was leading a relatively joyful life."

His longest-held post was a 12-year stint as pastor of Mount Oliver's St. Joseph Church. "I loved the people there, and I felt like I was beginning to learn again," he says.

But then came a bitter lesson.

In the early 1990s, congregations were shrinking in Catholic parishes in Pittsburgh and around the country. The Catholic Church responded by closing churches and consolidating parishes -- decisions that were rarely welcomed by the faithful. Mount Oliver, from which Hausen and two assistant priests were reassigned in 1992, was no exception.

"Our community was strong, and there was no reason to do this," Hausen says. "The congregation was very angry."

Hausen felt Catholic leaders needed to stop closing churches -- and start opening their eyes. Many of the problems the church faced, he thought, stemmed from its adherence to teachings that were increasingly out of step with how people lived: prohibitions on birth control, a ban against female priests, required celibacy for ordained males. Until the church abandoned centuries-old tenets, he thought, more churches would close.

Even so, Hausen says he was "overwhelmed by the prospect of changing 2,000 years of tradition." So, he says, "I held my peace."

And he retreated to two safe havens: scholarship and alcoholism.

Instead of becoming an assistant priest in a new parish, Hausen chose to study philosophy at the University of Notre Dame in 1992 and 1993. This is where Hausen says he "was really exposed to top-shelf theology": the postmodernism of Martin Heidegger, the comparative religion of Joseph Campbell; and the writings of Leo Tolstoy.

And this is where Hausen began drinking heavily.

Before 1992, he says, alcohol was a pastime: He drank in moderation with friends, or alone at home. But, "When I went to Notre Dame, I was so depressed about what happened" at St. Joseph's, he says. He admits being consumed with "self-pity and anger," some of which was fueled by his research, and his inability "to freely communicate my newfound ideas" because they conflicted with "Official Catholic Dogma."

He thought he was publicly hiding his problems. But, before he left for spring break, in April 1993, the dean of his department slid a note under his door telling Hausen to "do something about your drinking before classes resume." This was a "wake-up call," Hausen says: He got rid of his booze, ending a binge that had lasted since the previous September.

Over spring break, he checked himself into rehab at St. Francis Hospital, in Bloomfield. After a week of treatment, he was released, and returned to Notre Dame. He joined Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). He stayed clean through the rest of the academic year, and into his next parish placement, in 1993, at St. Margaret Church, in Moon Township.

Hausen remembers the next years as a difficult time filled with introspective study and questions about his faith. He became further involved in AA, and attended meetings more frequently. But he also continued battling alcohol abuse.

And in 2000, he took post at St. James Church, in Sewickley. It was here, in this quiet Ohio Valley suburb, that his final break with the church would begin.

As he had done in other churches, Hausen taught weeknight Bible-study courses at St. James. But by this point, he'd been fired by his scholarship and his belief that the church had lost its way. He began thinking -- and teaching -- outside church doctrine.

According to Father Ronald P. Lengwin, spokesman for the Pittsburgh Diocese, priests don't have to avoid controversial issues like female ordination or birth control. They "can present both sides of an issue," Lengwin says, "but they are also required to fairly and clearly present the teachings of the Catholic Church."

But Hausen acknowledges that during the classes, he argued that women should be allowed into the priesthood. He challenged mandatory celibacy for priests. He often stated that the pope and bishops should "share their real power with qualified lay persons." He referred to the papacy as "the last monarchy," and relished pointing out what he called "the illogic of the Catholic stance on birth control."

And even then, the Catholic Church was contending with allegations of child molestation by priests, which wracked the faith all the way to the Vatican.

"Everybody was very upset, and I was angry," Hausen says. "I was mad at the guys who were accused -- who had done these very wrong and evil things -- but I was mostly mad at the [church] authorities. I was mad at how the bishops had [hidden] this information for so long, and that they just tried to cover it up" -- the sexual abuse of children -- "without giving [the accused priests] hell, or caring for the victims [of these crimes]."

So Hausen decided to speak out.

On March 31, 2002 -- Easter Sunday -- Hausen gave a sermon outlining his beliefs about birth control and celibacy. He said church leadership should extend beyond those who are "predominantly white, male and celibate," and that a more tolerant church might have avoided the scandals currently rocking the faith. Catholics, he added, should be "pissed off" by the abuses, and the willingness of some church officials to conceal them.

Many in the congregation applauded Hausen's remarks: One believer told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, "I want a priest who can talk to me in terms of what is going on in real life, and that's what he did." But the next day, Hausen was stripped of his post.

Hausen was reassigned to Sacred Heart, the church of his childhood. Hausen had become too divisive to remain in Sewickley, Lengwin told the Post-Gazette: "Some [at St. James] support him and many do not. ... It was a pastoral response to a difficult situation, one which Father Hausen agreed with."

At the time, Hausen says, he did. Days after his homily, the St. James church bulletin published a letter from Hausen, in which he apologized for using the phrase "pissed off" -- and "for bringing into the pulpit subject matter that should have been reserved to classroom discussion."

But as the church's rebuke sank in, Hausen's resentments increased. At Sacred Heart, Hausen says he was allowed to say limited public masses until October 2003, when he was placed on "administrative leave." The diocese said it took the step because of Hausen's worsening trouble with alcohol, and Hausen doesn't deny that his problems persisted.

Between October 2003, and April 2004, Hausen and a group of 14 others -- mostly friends and parishioners from St. James -- began organizing a new church.

Hausen knew the potential consequences of starting a splinter parish -- that he'd effectively excommunicate himself. And while the days of being burned at the stake had long since ended, there were very real consequences for that action. For starters, it meant that after more than three decades in the church, Hausen would be giving up the benefits the church usually offers to retired priests.

"If you leave the church, you are no longer eligible for benefits," Lengwin says. "It's not a pension, so priests don't pay into it; the fund comes from each parish's diocesan dues. If a priest is no longer in the diocese, he can no longer claim its benefits."

But Hausen felt he could not turn back from what he believed. And neither could the dozen people who began meeting with him Saturday evenings, at Ginger Walker's home in Sewickley.

Walker, then in her mid-50s, says she'd been a lifelong Roman Catholic, but believed Hausen was "doing the right thing."

Hausen "is a true and decent friend," she says, who consoled her through the night her husband passed away. "[Hausen] came to my home, came to the funeral home, and asked questions about [my husband] when I most needed help." She defends Hausen as "very personable and kind, and it just seemed like him and I were friends immediately." She says, when Hausen decided to start his own parish, it "wasn't even a choice with me -- I just knew I had to follow him."

Other faiths, Walker says, "teach by fear. And FB doesn't. He loves us. Loves us all. I mean, how many guys would give up their pension and everything they worked all their life for, like he did? My guess is not too many."

I attended Hausen's first Mass with CHECC, on May 2, 2004, and sat with some 300 people -- including a number of reporters and newscasters -- in a rented ballroom at the Sewickley Country Inn. Hausen's flair for showmanship was evident: As an introduction to his homily, he raised his hands and his eyes toward the ceiling and said, "God, if it's a sin to be excommunicated, strike me down right now."

God didn't strike, but the church did. The very day of Hausen's service, the church drafted a statement of excommunication, which Hausen keeps in his office to this day:

[T]he Reverend C. William Hausen, an incardinated priest of the Diocese of Pittsburgh, conducted liturgical and sacramental rites at his newly established church named the Christ Hope Ecumenical Catholic Church located in Sewickley, Pennsylvania. By this canon, Father Hausen has willfully separated himself from the ecclesiastical governance of the Catholic Church and the Bishop of the Diocese of Pittsburgh. This formal act of separation from the Catholic Church by performing liturgical and sacramental rites in a church not authorized by the Catholic Church constitutes schism.

Years later, Hausen would say the excommunication hit him like "a bolt of lightning." In the words before him, he said, he beheld the same intolerance "which held priests in bondage since the Middle Ages, Women in bondage since Constantine, the laity and human sexuality in bondage since Augustine, and human reason in bondage since the Council of Trent."

The church itself chose slightly more secular rhetoric in a public statement explaining its decision: "In the sports world, if a player for the Pittsburgh Steelers becomes a free agent and signs with the Cleveland Browns he is certainly free to do so," the statement says. "To continue to wear a Pittsburgh Steeler jersey and claim to be a Steeler is simply false advertising."

The statement also had a message for anyone tempted to follow Hausen: "[F]ree and willful participation in [Hausen's church] implies separation from the Catholic Church" -- or, a self-imposed excommunication. It quotes Lengwin saying, "We are all saddened by Father William Hausen's decision to start his own church, and continue to hold out hope that he will return."

Others were happy to see Hausen go.

"This is a lost soul who is, it seems, quite happy to continue to lead others astray," wrote Lane Core Jr., a prolific blogger and occasional contributor to the Pittsburgh Catholic newspaper. "But he's also a recalcitrant, contumacious, rebellious subversive, and it's far better -- it's simply honest -- to have His Lostness lead others astray from a banquet room than from a Catholic Church."

Ironically, however, Masses at CHECC remain very similar to those celebrated in traditional Catholic churches. Hausen says that's in large part so that "Recovering Roman Catholics" -- who are CHECC's target audience -- will feel at home. "The ritual most common to the people of Christ Hope is the [Roman Catholic] Mass," Hausen says. And he believes that Mass "is good, with the changes I have made."

Chief among those changes is an emphasis on love and inclusion, rather than power or authority. The first line of CHECC's processional hymn, for example, celebrates the "Holy Lord God all-loving" rather than the "Hold Lord God almighty" worshipped in the Catholic Mass. And at CHECC, the prayer most Catholics know as the "Our Father" refers to "Our Father-Mother" instead.

There's also a tradition, during the Lord's Prayer, of not only holding hands, but actually leaving the pew seats to physically gather in a circle, close to the altar, to clumsily sing the Lord's Prayer in a tune no one -- including Hausen -- quite seems to know, and then sharing a hug or handshake with the person next to you. In the Mass, every action focuses on openness, and community.

It's a spirit described on Christ Hope's Web site (www.christhope.com):

Spirituality, in our community, means sharing God's love with whomever we encounter ... the best way we can, imperfect as that may be. The word 'God' means loving others as Jesus loved. All Persons are welcome to our Communion Table. ... We are persons from diverse backgrounds. We are positive and not interested in old battles. We too are searching for more meaning in our lives, in our Interpersonal Relationships.

So come around some Sunday and see what we are all about. We will, at least, give you a cup of coffee and a cookie.

That openness reflects Hausen's reading of such thinkers as Eckhart Tolle, author of the popular religious tract A New Earth. For Hausen, the book's success shows that "there is now a universal shift of consciousness taking place, and a desire to find God within, not up there, somewhere." Hausen says Tolle "teaches the five world religions -- Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity and Islam -- and finds that the word 'compassion' is the unifying theme of them all."

So why leave the church at all?

For Hausen, the time to leave a church is "when a dogma becomes emotionally and intellectually too hard to believe in, and affects one's daily life for the worse. ... When one finally understands, emotionally and intellectually, that there is no absolute certain knowledge, and that all knowledge is limited, and their church continues down its merry way of arrogant certitude, it's time to leave."

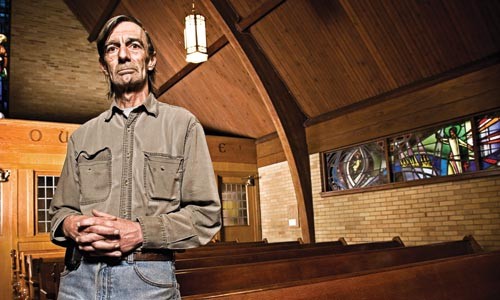

Clearly, others have heard the same call. Hausen's following is small but devoted: Over nearly two months, I've attended CHECC events ranging from services to board meetings, envelope-stuffing sessions to rummage sales. And there's no questioning the commitment of the church's core. You'll find, for example, Dave Boehm, the skinny, tattooed dishwasher who shows up for any kind of manual labor he can fit into his schedule, and who takes notes at all the board meetings. There's the family of three from Mount Lebanon, and "Earlobe Joe," whom Hausen helped out of homelessness. And above all, there is Ginger Walker.

And in a church, Hausen says, that community is as important as the dogmas he left behind.

"Teachings are certainly important," Hausen says, "but should not be proffered as absolute truth or dogmatic certitude. A sense of community is just as important as its teachings." And a church is the place "where one embodies one's beliefs in actual community ... a litmus test of reality."

For Hausen and his church, though, the outcome of that test is still in doubt.

There's nothing new about Catholic dissidents. The church itself owes much of its substance to them. Established orders like the Franciscans and the Jesuits took root when charismatic leaders wanted to practice their faith in a new way -- and ended up reforming the church as they found it.

"They became incorporated into the larger church rather than forming new churches," says Maureen R. O'Brien, associate professor of theology and director of Pastoral Ministry at Duquesne University. Similarly, she notes, "some faithful Catholics today choose to be vocal critics of the institutional church while remaining within it." By way of example she cites Voice of the Faithful -- a Boston-based organization that, like Hausen, was outraged by priest child-abuse scandals. Even so, O'Brien notes, while "[t]he members want to make the institutional church accountable for the abuses ... they aren't seceding from the church."

Closer to home are people like Joan Houk, who considers herself an excommunicated Roman Catholic priest, much like Hausen. In 2006, she and 11 other women aboard the Gateway Clipper were "ordained" as part of an international movement called Roman Catholic Womenpriests. Church officials denounced the participants, and the Vatican has no intention of recognizing these ordinations. But Houk still attends Mass at St. Alexis Church in McCandless. Hausen has approached Houk about becoming a regular priest at CHECC, but she has declined because her energies "are focused on changing Roman Catholic doctrine from within the church as opposed to outside it.

"I'm still in love with the church," she says. "You can call my actions 'protesting,' but I think it's for the good of the church. ... Things happen very slowly with Catholics, and I may not be [alive] when women are allowed to [serve as priests], but I think it's a duty to try to change the church, to make it better."

Sometimes, of course, such reconciliation isn't possible. Breakaway sects become thriving faiths in their own right -- as in the case of Protestantism -- or are stamped out, like the Cathars subjected to the Inquisition. But many groups simply fade away: Members live outside the faith for a time, but gradually disperse.

Many factors determine which faiths will succeed over time, says O'Brien. "But it does seem that the groups which endure have to establish some new structure to replace the one that they've rejected. People need some common beliefs and structures that support those beliefs to help hold them together." She notes that some early communities inspired by the teaching of Jesus, for example, "dissolved because the members all felt individually inspired by God and couldn't agree about how to be a community together over the long term."

In the early days, certainly, it seemed as though the CHECC might take root.

Among the church's early supporters were anonymous donors -- two close friends and an out-of-state philanthropist inspired by Hausen's Easter homily -- who provided the money needed to purchase the church's $215,000 Brighton Heights property in 2007.

I kept up with Hausen's progress through word of mouth and occasional media reports. During a February 2006 meeting at the Bellevue Eat'n Park, he talked excitedly of promises of support from friends and people from well outside the region -- all impressed by his dedication to his beliefs, he said.

But things began to fray. Two church co-pastors, who were married to each other in keeping with Hausen's beliefs about an open clergy, ended up leaving the church due to marital problems. (Hausen remains unmarried, despite lifting the celibacy requirement, but he declines to discuss romantic attachments: "That's too personal a question," he says.) But the real problem has been a less dramatic, but seemingly inexorable, decline in members. Instead of being struck by lightning, Hausen has witnessed a steady drop in attendees. Services which once drew upward of 300 people now draw one-tenth that, and most of those in the pews are in their 50s or 60s. Every service seems to bring news of another member of the church's extended family dying away.

Today, Hausen acknowledges "[t]his whole church is on shaky ground."

Hausen himself returned to rehab this past May. His congregants willingly paid for the treatment -- a testament to the church's enduring sense of community. But there's a sense that this is a church for people in recovery ... not for those who have recovered. Hausen's break with the Catholic Church is just one trauma of many that have yet to heal.

Every Wednesday, for example, CHECC holds a meeting called Emotions Anonymous. Hausen jokingly refers to these meetings as "The Effexor Club" -- named after a prescription antidepressant used to treat clinical sadness and anxiety disorders. Participants spend two or three hours sharing their loneliness, exhaustion -- the emptiness of life and the certainty of death, the decisions we want to make but can't, and the decisions we wish we'd made long ago.

The week I attended, it was particularly difficult because Ned Copenhaver -- who'd asked about how Jesus treated tax-collectors and Gentiles just two days before -- had died of an unexpected heart attack. Hausen was beside himself with grief. Ned had recently gotten out of prison and begun attending services with his parents. He was on his way, Hausen said, "to a full life and a full recovery."

Hausen's own future remains uncertain. At age 70, he receives some money from Social Security, but he has petitioned Pittsburgh Bishop David Zubik to reinstate his retirement benefits. So far, Hausen says, Zubik has promised only to pray for him.

"I sincerely hope Bill can get a pension. He certainly gave the diocese many years of faithful service," says Father Jack O'Malley, who serves as chaplain for the Allegheny County Labor Council. "He certainly did a fine job while he was with the church. We're supposed to be about justice, aren't we?"

In the end, though, it may be that Hausen's faith simply won't reap its rewards in the temporal world.

Ginger Walker, Hausen's friend and the most consistent attendee at CHECC services, says that when people learn she's abandoned the Catholic faith, they sometimes ask, "Aren't you afraid you're not going to heaven?" That, she says, "is the dumbest remark I've ever heard. "

"I don't care what religion you are -- FB says you're going to go someplace nice, and that's what I believe."