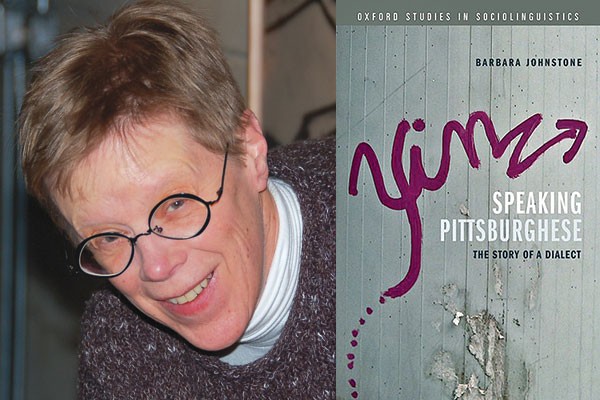

For years, Carnegie Mellon University professor Barbara Johnstone has been the world's foremost expert on Pittsburgh's unique speech patterns. But don't expect to use her book Speaking Pittsburghese: The story of a dialect as a phrasebook for negotiating the Strip District on a Saturday morning.

Published by Oxford University Press and currently available on amazon.com, Speaking Pittsburghese is both academic and accessible. It charts the unlikely story of a city whose residents went from barely recognizing they had an accent to celebrating it as a touchstone of their identity. As Johnstone writes, "Due to a particular set of geographical, economic, linguistic and ideological circumstances, people in Pittsburgh grabbed onto language as a way of defining themselves."

In Johnstone's telling, those circumstances included both the collapse of the steel industry and an event just prior to it: the early-1980s publication of Sam McCool's New Pittsburghese. McCool's book — and later, Internet chatrooms that allowed Pittsburghers to share nostalgia over speech patterns — helped departing Pittsburghers carry a bit of home with them as they searched for jobs elsewhere. And once they moved to new cities, they were even more struck by how singular Pittsburgh's accent was. (One reason "yinz" has assumed such local prominence, Johnstone surmises, is because so many Pittsburghers moved south, where they couldn't help but be struck by its contrast with "y'all.")

Meanwhile, Johnstone documents, the Pittsburghers who remained behind created a cottage industry celebrating the local dialect on T-shirts and coffee mugs. But those tchotchkes distorted Pittsburgh speech even as they helped define it: Much of what we think of as "Pittsburghese" — phrases like "j'eet jet?" — actually isn't unique to Pittsburgh at all.

In fact, many of those who most celebrate Pittsburghese are newcomers, who don't speak it correctly ... while some of those with the purest accents don't realize they have an accent at all. (Many locals, Johnstone writes, literally can't hear the difference between "hahs" and "house.") But whether you speak the accent well, or badly, Johnstone argues, you are part of a broader story: the tale of how Pittsburghers have made a "hahs" into a home.

I've often felt that one of Pittsburgh's most notable quirks is how much pride it takes in its own quirkiness. Is that true of our speech patterns as well? Do we have not just a different way of talking, but of talking about how we talk?

Not completely different. But there's a lot more consciousness of it, and it came a lot earlier. Now, you find some rather self-conscious, top-down efforts to market local speech in places like New Orleans, for example, as a way of rebranding the city after Katrina. But it never quite became the thing that it is in Pittsburgh. Philadelphia, there's a very distinct accent there, but it's never become part of the local identity in this way.

Is that because, linguistically speaking, Philadelphia sucks?

Actually, the most famous person in my field has studied Philadelphia. But he's not interested in the dialect as a cultural artifact in the same way — and it isn't a cultural artifact there the same way. So many random things had to come together.

I think part of it has to do with Pittsburgh's lack of self-confidence. There wasn't anything outside of steel — no one had really thought about the city in any other kind of way [until the industry collapsed]. And as part of the lead-up to that exodus, Sam McCool wrote that book, which had a big influence.

Some of the fascination with this stuff — all the T-shirts, for example — strikes me as being a case where, once people emigrate from an area, they cling to its traditions even more than the people they left behind.

That's a very common feature of diasporas. I think the Steeler Nation is like that — there was a wonderful article in the [Pittsburgh] Post-Gazette about how they were creating a Disney-fied version of the Pittsburgh of long ago. I think that was happening with language, too.

But now, I think, things have changed. It's not the same kind of representation of streetcars and city chicken — the Pittsburgh that was disappearing even in the 1950s. Instead of trying to evoke a vanished way of life when they represent Pittsburghese, people now are representing a particular persona. And that character is "the yinzer."

The stereotypical "yinzer" is always white and working-class. But lately there's been a sort of hipster celebration of it all: You can see Pittsburghese-themed crafts at Handmade Arcade, bought and sold by people who may not have an accent at all. In your research, how do native speakers feel about that?

That's a good question, and it's hard to answer because this wasn't happening even 10 years ago. They had the T-shirts, but the consumers were mostly Pittsburghers sending them to their relatives.

I think when outsiders start messing with Pittsburgh speech, it can easily sound patronizing. One reason people like Pittsburgh Dad is they can tell he's local. [Actor Curt Wootton] has an accent himself when you talk with him personally.

So can non-natives traffic in this sort of "jagoff paraphernalia" without being patronizing?

This is a question I get all the time. I've had rather hostile questions from fellow academics who say, "Why don't you talk about what's wrong with this? This is really objectionable." I just say, "I'm an ethnographer; I'm a describer of the culture."

And people are not offended by this. I think people can do this lovingly, and I think a lot of the hipster stuff is kind of loving.

Still, isn't there kind of painful paradox here? The Pittsburgh accent seems more popular than ever, even as the city's local working-class identity is dwindling. It's like the same thing that makes us cling to the accent is also what's pulling it away from us.

Exactly. And Pittsburgh is staking its future on the same things every other city is staking its future on. One group of people who are not interested in Pittsburghese are the people trying to plan the economic future of the area. During the G-20, people who were serving as hosts were instructed not to speak Pittsburghese. And they didn't even know what they were being asked not to do. ...

This is what happens in globalization in general. Globalization has been going on here forever: The fact that the Scots-Irish came here in the first place was globalization. But there's that famous quote from sociologist Anthony Giddens: Globalization unites as it divides, and divides as it unites. People get thrown together with people who aren't like them, and you talk more like the other person, because you want to be understood. But at the same time, you're drawn to notice what is different. There's an inevitable process of accommodation. Kids go to college and automatically accommodate their speech to other people — at exactly the same time they are talking about how they talk differently from each other.

So is the moment that Pittsburghers became aware of their accent also the moment where they were destined to lose it?

The process of losing it is in place, though it doesn't mean you yourself will lose it. It's really hard to just change your accent, especially for adults. But certain forms, certain words, certain sounds, have become stigmatized — they're widely thought of as things that educated people don't do. That means those particular forms, like "dahntahn," are going to go away.

You've been researching Pittsburgh speech patterns for years. Are you tired of it?

There are still a few things I want to do. But I feel like I've told the story as it can be told.

One of the things I'm interested in now is "stance" — which means how you stand, but also aspects of how you talk. So I'm really interested in how Pittsburgh Dad moves. Because what he's stylizing is not just the language but the facial expressions, and what he does with his hands.

When you see people imitating Pittsburghese, they do that. It's getting so that this yinzer stuff is about that whole stance: talking with a louder voice, and a higher voice, and talking about certain things, like being frustrated and feeling powerless.

Which gets back to the idea that Pittsburghese is defined by some local ambivalence about a globalized, post-industrial economy. So will you and I someday be talking about how our body language has a Pittsburgh accent too?

I don't think a set of gestures is associated with a dialect so much as a persona. If you had someone stylizing a classic working-class guy from almost anywhere, you'd get that — tough, but frustrated.