Interest in Turner’s case has surged every few months in 2021 after spiking at the end of 2020, coinciding with the one-year anniversary of her disappearance. The most recent spike in mid-September on Google Trends follows the disappearance of Gabby Petito, a 22-year-old woman who was later found dead from strangulation in Wyoming after traveling with her boyfriend on a cross-country roadtrip.

As Petito’s case garnered national attention from legacy media, people on social media became fascinated with the case, with the news cycle picking up on and responding to that interest. But with Petito’s case in the spotlight, many pointed out the disproportionate media attention missing white women receive relative to missing Black women, such as Turner.

Multiple factors, including racial bias in police organizations and media who report on crime, limited police communication, and what social media audiences amplify, can all lead to white missing persons getting disproportionate attention. Case-specific factors also play a role, including when narratives common in true crime media are present or when there is more information available about a particular case. But for family and friends of missing persons, including those here in Pittsburgh, cycles of grief remain open.

Pittsburgh teaching artist Marcè Nixon-Washington met Turner in 2018 through the Braddock Library, and remembers how difficult it was when her friend first disappeared.

“I can just remember the first week, and just feeling like that was so long. And just waiting for answers. And then now, it's like two years and no one really teaches you what to do with that. No one knows what to do with that. Because you just don't know,” says Nixon-Washington. “And that's the hardest part, is just not knowing anything at all.”

Dr. Gina Masullo, an associate professor in journalism at the University of Texas at Austin, says the disparity in media coverage between missing white women and missing Black, Brown, and Indigenous women is rooted in white supremacy.

“The basic thing is that we live in a society that values different people differently. There's more attention paid to missing white women, missing white children, because society as a whole is systemically biased towards white people,” Masullo says. “So this plays out both in law enforcement and in the media.”

More than three-quarters of U.S. newsrooms are white, which is higher than the percentage for all U.S. workers, according to the Pew Research Center. And predominantly white newsrooms in the U.S. lead to inferential bias about who is considered important and relatable, since missing white women are more likely to remind them of their own family members, according to Masullo. Editors also make decisions about what they believe their readers will pay attention to, and implicit biases shaped by white supremacy can inflate the importance of missing white women relative to others.

“Both print and broadcast journalists depend on police to alert them to a missing persons case,” says the study from Liebler. “For journalists, police involvement in a case signaled that the case was legitimate, or as one news director stated, that it had been ‘vetted by a police agency.’”

On the flip side, Liebler et al.’s interviews with police revealed that they were accustomed to local media accepting police requests to highlight missing children’s cases, although law enforcement also made decisions about which cases were “newsworthy” before taking them to members of the media.

Liebler points to social media as a way of supplementing coverage in legacy media, since it allows for stories to be shared more immediately and broadly. While this can help increase visibility, it is still dependent on the media, and particularly police, posting and sharing these stories.

Family and friends often shoulder the responsibility of putting pressure on media and police to continue coverage and focus on a case. But some families and communities have more resources than others who are left with few people to advocate for them. Masullo notes that white supremacy also affects who is more likely to be believed and taken seriously when they do reach out.

Social media also plays a part, since police alerts can be shared as soon as they’re posted. If legacy media has insufficient resources to write about or cover a missing person more fully, they can still share posts and amplify the case. Readers and audiences can also play a bigger part in spreading the story, which can increase the likelihood of the story reaching someone with relevant information. It can also help sustain pressure on media and police to continue coverage and investigations.

While social media can help amplify stories of missing people and fill in the gaps of legacy media coverage, people can also unintentionally spread misinformation or drown out useful information. Social media can also reproduce uneven and disproportionate attention to some cases, particularly when themes common in true crime narratives seem to be involved.

In Petito’s case, people on social media picked up on the concurrent narrative of domestic violence within her relationship. There was also personal information about Petito available on social media, as well as a person of interest identified for the case, which may have fueled interest, whereas cases like Turner’s do not have an alleged perpetrator.

Little information has been released about Turner’s disappearance. Details from the investigation determined that she was last seen by a bus driver after leaving Dobra Tea in Squirrel Hill, and that her wallet, cell phone, and keys were later discovered.

Still, legacy media and police’s attention to a case can act as catalysts for social media attention, as well as shape later conversations about a case. Nixon-Washington remains frustrated that legacy media dismissed Turner’s disappearance as a suicide, and she notes the power that legacy media has to bring attention to cases.

“We can sit there, we could protest in front of the buildings all we want, but if no one's covering it, and if no one's showing the entire world it, then it's kind of just, like, ‘All right, yeah, it's just gonna keep happening, but who really cares?’” Nixon-Washington says. “I think it's truly, like, checking our own biases and checking the pieces of, like ... how am I policing who gets media coverage? Because even beyond Turner, there's so many other people missing that need their story to be out there.”

The National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs), a missing persons database through the U.S. Department of Justice, lists 30 missing persons in Pittsburgh. Their dates of last contact stretch back to 1962, and it is unclear which cases are still open.

Pittsburgh Police public information officer Cara Cruz says that, as of Oct. 6, Pittsburgh Bureau of Police Special Victims Unit has eight open cases of missing persons: five Black men, one Black woman, and two white women. These eight cases represent less than 2% of all 433 reported cases in Pittsburgh in 2021.

Cruz notes that no two cases are alike and that circumstances and details can be highly nuanced. For family and friends of missing persons, however, the difficulty of solving cases is personal and prolongs the pain of not knowing where their loved one is. Nixon-Washington remembers police ignoring or waiting until the next day to follow up on leads, which she felt was too long to wait.

“I feel like it wasn't investigated as well as it could have been,” Nixon-Washington says. “And I'm wondering if there's still space to kind of reconcile that. And if there's still space to actually search and actually look and actually do any of this.”

The search for Turner continues, and her loved ones hold on to reminders of the multidisciplinary artist. Sydnee recently decorated the house she shares with her mother and grandmother with Turner’s art. Nixon-Washington continues to hold onto a bowl brought back from a 2019 study abroad trip to China to give to Turner.

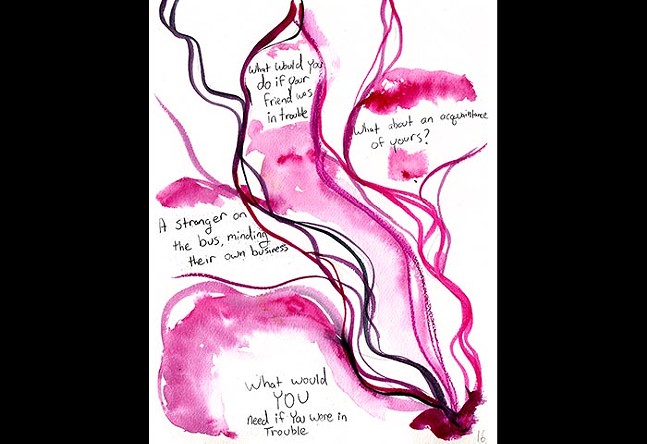

Nixon-Washington also creates art inspired by Turner and other missing persons, including a mural originally placed in Braddock created with muralist Sandy Kessler Kaminski. She also contributed ceramic pieces for an Oct. 21 exhibit, Call Me When You Get Home, a “multimedia call and response experience to activate the power of remembering, reclaiming, and envisioning safety centered in collective joy.” The show was presented in conjunction with local artists Sheba Gittens and Jayla Patton, and curated by Sister IAsia Thomas.

“It has always been a crisis. I will say that it has become more in our faces now, but it was always a crisis. But when you know Tonee, it's like, ‘Huh? Tonee is missing? Like, why isn't she found?’” Nixon-Washington says. “It's kind of really heartbreaking and it's just really scary, and it's still scary to this day because we have no idea.”

Turner’s loved ones and community have also celebrated and remembered her through a dance party in February 2020, as well as a march in December 2020 for the one-year anniversary of her disappearance. During a birthday celebration for Turner earlier this year, artist Sarah Tancred guided people through making clay flowers, which are symbolic for missing women of color. Turner herself worked with ceramics, in addition to painting, pastels, smelting, and more.

“Tonee is a human being, and she deserves justice, and she deserves the dignity that all human beings deserve as soon as they’re born,” Sydnee told Hayes-Freeland. “If you have information on my sister Tonee, and you know where she is or anything that could bring her story or her to light, you should stop withholding that so you can have a lighter life ... and allow Tonee to regain the human dignity she deserves, so she doesn’t have to continue being missing.”

If you have information about a missing person in Pittsburgh, contact the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police at 412-323-7800 or call 911.