Pittsburgh City Paper’s article about Fox Chapel as a sundown town elicited a lot of strong reactions. Some people objected to describing the borough as a “sundown town.” Others acknowledged Fox Chapel’s exclusionary history but claimed the community has moved on and is now welcoming to all people.

And then there were the people for whom the article hit home. People in the last group shared recent examples of racial hostility and the many reasons why Fox Chapel’s demographic profile still looks like it did nearly a century ago.

There were no known lynchings in Fox Chapel, and there were no episodes of racial violence like the 1909 roundup of Hill District residents or the racial massacres that happened in Elaine, Ark., in 1919 and Tulsa, Okla., in 1921. Yet, public policies and private land transactions made Fox Chapel a place for white people only for most of its history. The borough remains one of a handful of Pittsburgh communities that some Black homebuyers say they avoid, and where many Black Pittsburghers do not feel comfortable visiting.

Sociologist James Loewen, author of the 2005 book, “Sundown Towns: a hidden dimension of American racism,” published an essay in 2016 aimed at journalists and historians. He asked them to consider one question: “If [a town] is overwhelmingly monoracial, decade after decade, ask why.”

City Paper did that in our first article. We asked borough officials and combed through historical records to show that Fox Chapel’s history fit the sundown town model.

But what about Fox Chapel today? There must be reasons why its zoning remains exclusionary by some definitions and why Black residents comprise only one percent (64 out of 5,343 people) of the borough’s population.

Breaking the Color Barrier in Fox Chapel

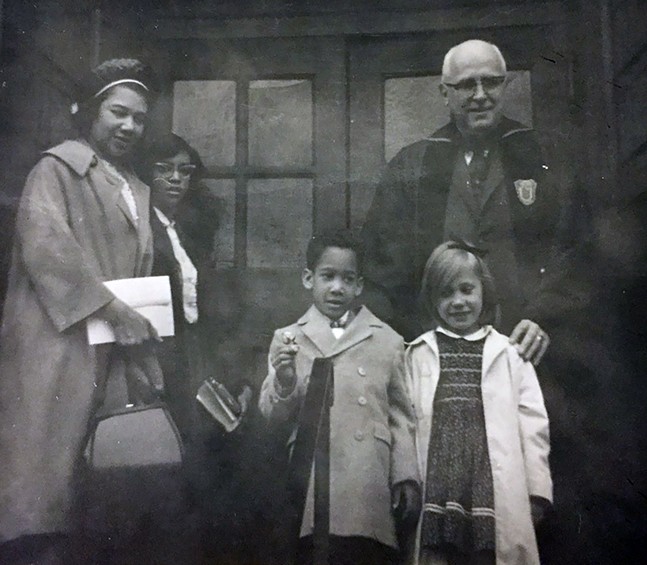

Marshall McDonald is a Grammy-winning musician who grew up in Fox Chapel. His father, Alonzo, was an oral surgeon, and his mother, Inez, was a civil rights activist. The McDonalds might have been the first Black people to buy a home there. The five-member family was among the 23 Black residents — 22% of Fox Chapel’s Black population — recorded in the 1970 census.

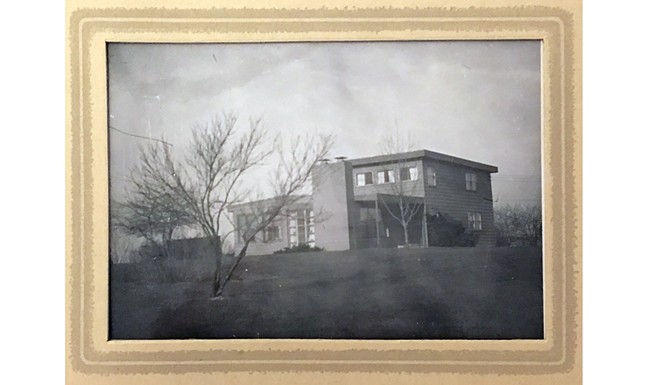

Two Carnegie Mellon University economics professors paved the way for the McDonalds to move into Fox Chapel. James Houghteling Jr. bought 15 Chapel Ridge Rd. in January 1964. He owned a Squirrel Hill home when he bought the Fox Chapel house with the intention of reselling it, which he eventually did, to the McDonalds. Houghteling was a straw buyer: a white man who bought property from another white person who did not want to sell to Black buyers.

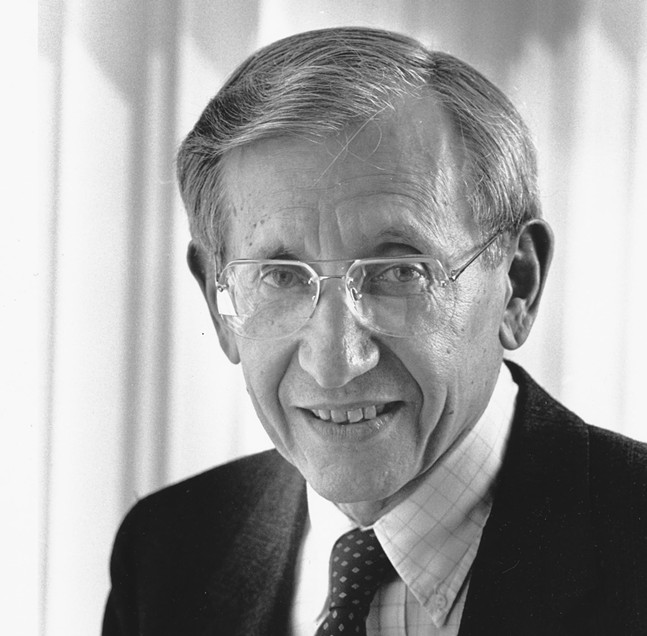

At the time, Richard Cyert and his family lived a few houses away from 15 Chapel Ridge Rd. A colleague of Houghteling’s in CMU’s Economics Department, Cyert became the university’s president in 1972. The Cyert and McDonald families attended the First Unitarian Church in Shadyside and they became friends prior to the McDonalds' move.

Marshall McDonald was in elementary school when his family moved into the Chapel Ridge Rd. home, and he recalls the hostile environment his family moved into. A neighbor called him a “monkey” and other names while waiting for the school bus. Still, the family bought the house from Houghteling five months later.

“The police were stationed outside of our house when we first moved there,” McDonald remembers his mother telling him. “The police also told her to keep me away from the windows because they were afraid that someone would try to shoot through the window.”

The Cyerts had three daughters. They have remained friends with Marshall. Steffes recalls the ostracism their family faced after the McDonalds moved onto the street. “I was told by a couple of the families when I went over to play with my neighborhood friends that I was no longer welcome in their home,” Steffes tells Pittsburgh City Paper.

The other kids, Steffes vividly remembers, called her family “n— lovers.”

They resisted the community’s racism by avoiding segregated places like the Chapel Gate Swimming Club, which opened in O’Hara Township in 1960. “We had to have our own swimming pool because we weren't allowed to swim in any of the other pools because Blacks and other races weren't allowed,” Steffes says.

“The only Black people who could come in [there were] ... nannies, people who are watching the children,” says Lynn Cyert, Steffes’ older sister.

Don’t live where you’re not wanted

More recent examples include a Black cyclist who told CP about the racial slurs shouted to their group by drivers as they rode through the borough. “We started on the North Side, came through Millvale, Aspinwall to Fox Chapel,” says the cyclist who asked that we not name them. “So as we're going up the hill, this truck rides past and starts calling us, you know, n-word.”

Then, another truck passed. “And you could tell they were white men, [they] called us the n-word.”

It’s reasons like the cyclist’s experience, and the episodes recounted by the McDonald and Cyert families, that perpetuate Fox Chapel’s uneven racial makeup.

The cyclist was born in the Hill District and now lives in Penn Hills. “When I looked for my house … I was not looking anywhere but either Penn Hills or Monroeville. You're not looking in Fox Chapel,” they tell CP. “My mother always told me, don't live nowhere you’re not wanted. Don't go nowhere where you're not wanted. And you know, nobody wants to be in the middle of some racist [people].”

Biking through Fox Chapel dredged up familiar and unpleasant memories. The first time they were called the n-word as a child is indelibly etched in their memory. They were waiting for a trolley to take them from the Hill District to Brashear High School.

“This old man who was, like the town little drunk or crazy, he kept repeating the word ‘[n—]’” they say. “I can remember each time it happened to me. Nobody forgets that.”

Rob Jones is a Black man whose family has lived in Pittsburgh since the early 1900s. He describes a climate where passive acceptance of racist behavior is the norm.

“This stuff is [on] automatic pilot,” he says. “You don't really have to do anything. You don't have to pass any ordinances, you don’t have to have those exclusive covenants. You just don't have to do anything.”

All the work to make Fox Chapel exclusionary was completed decades ago.

“Whether you look at Fox Chapel or Upper St. Clair, it's just all the same dynamic where … government, either local or all the way up to federal, implements certain policies as long as you can get away with them for a decade or two or five,” Jones says. “After that, you can take the signs down because all of the rest of this stuff happens organically and you don't have to do anything.”

Fox Chapel’s invisible walls worked well enough to keep Cheryl Hall-Russell from looking for a home there when she moved to Pittsburgh 13 years ago. The community looked good on paper, especially the highly rated school system, and she could have afforded the area’s prices.

Then she talked to longtime Pittsburgh residents and heard stories about Black children being marginalized because of their race. And, she heard stories about Fox Chapel being openly hostile towards Black people.

“They understood that Black families were not welcome there,” she says. “And so, once you've established that, it is very difficult to forget that history.”

Fox Chapel’s history and stories about racial hostility continue to make the borough unappealing to some Black homebuyers. The high price tags for many Fox Chapel homes keep the borough exclusive; its racism makes it exclusionary. “There's a difference between exclusive and exclusion,” says Jones.

CP reached out to borough officials for comments on the earlier story. We also wanted to know more about diversity in the borough’s workforce and Fox Chapel’s current demographics. We got no responses by press time.