The proposed extension of the Mon-Fayette Expressway is the highway plan that just won’t die. The raised, four-lane express toll-road from Jefferson Hills through Duquesne to Monroeville has been started and stalled so many times since the idea was first dreamed up in the late 1950s, that some have nicknamed it the “zombie highway.”

Sustainable-development nonprofit PennFuture has campaigned against the Mon-Fayette for years and gave it the undead moniker in 2015. “It is the zombie highway because you can’t kill it,” says Andrea Boykowycz, formerly of PennFuture. “It’s impossible to kill.”

But there’s a reason the Mon-Fayette won’t stay buried: It’s been embedded into the Mon Valley’s hopes and dreams for decades. The highway was first proposed as a way to increase productivity of the steel and industrial facilities that hummed along the Monongahela River in the 1950s, but it was scrapped due to lack of funding. It was proposed again in the mid-1980s to help revitalize the Mon Valley, which had seen massive decline with the collapse of Pittsburgh’s steel industry, but funding remained an issue.

Since then, every several years, the Mon-Fayette gets floated as the big idea to help revitalize the Mon Valley, which suffers from some of the worst unemployment in the Pittsburgh region. But critics recognize the highway’s serious issues, like its high price tag and the lengthy completion timeline. Additionally, the project never actually materializes.

“It’s almost a meaningless promise, but it also serves as gospel,” says Boykowycz.

Regardless, a powerful group of state politicians and business leaders believes the Mon-Fayette is still the answer. However, critics, including town supervisors and activists, say the Mon Valley should instead make improvements to existing infrastructure with Complete Streets policies — where road design equally accommodates drivers, pedestrians, public transit and cyclists — believing that will spur economic development.

Whether the Mon-Fayette could revive the Mon-Valley economy or not is up for debate, but it appears the discussion isn’t fading away anytime soon.

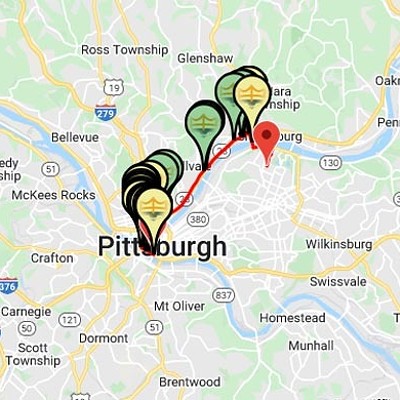

The Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission, which is tasked with designing and constructing the Mon-Fayette, says funding will come from the state tax that drivers pay for gasoline, and the group is in process of renewing the Mon-Fayette’s approval with Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission, a transportation and development-planning agency. The Turnpike Commission currently projects a $2.1 billion price-tag for the 14-mile highway connecting two suburban municipalities.

According to Turnpike Commission spokesperson Carl DeFebo, the highway extension should receive 37,000 vehicles a day in 2045. DeFebo says current designs show the commission will need to acquire land on 689 properties, including 237 residences, to complete construction of the Mon-Fayette. A toll amount hasn’t been finalized for the Mon-Fayette, but DeFebo says it will be comparable to other Turnpike extensions in the region, like the Beaver Valley Expressway. (These cashless tolls require drivers to have an E-Z Pass.)

DeFebo says that the commission is merely the facilitator of the project, not its advocate. “The [Turnpike Commission] was directed to advance this project as well as other projects by the [state] Legislature,” wrote DeFebo in an email to Pittsburgh City Paper. “Our role is not to advocate the expressway, but to design and construct it.”

Projects like the Mon-Fayette were given to the Turnpike Commission in 1986 thanks to the passage of state Act 61, which authorized the commission to undertake a program of capital improvements and construction projects. State Sen. Jim Brewster (D-McKeesport) still very much supports the Mon-Fayette, says his chief of staff Tim Joyce, citing its economic development potential.

“It opens up different opportunities,” says Joyce. “Businesses have always looked for the shortest roots to deliver their products, and a modern highway improves those options.”

Joyce points out old brownfield sites in Clairton, McKeesport and Duquesne as potential beneficiaries of the highway, even though the proposed Mon-Fayette route doesn’t directly connect to many of those sites.

“It’s close enough that the surrounding communities will take notice and benefit,” says Joyce. He adds that just because the highway is built doesn’t mean towns can’t also focus on streetscape improvements and redesigns.

However, history shows that large, raised expressways can have a negative effect on neighborhoods. According to a March 2016 Washington Post article, former U.S. Department of Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx, who grew up in a Charlotte neighborhood bisected by expressways, advocated for removing expressways in Miami, Los Angeles, New York City, Seattle and Baltimore because they sliced through and hurt neighborhoods. “It became clear to me only later on, that those freeways were there to carry people through my neighborhood, but never to my neighborhood,” said Foxx in the Post. “Businesses didn’t invest there. Grocery stores and pharmacies didn’t take the risk.” (Local politicians have cited similar effects from I-279 in the North Side.)

PennFuture CEO Larry Schweiger still believes the Mon-Fayette will hurt the Mon Valley, and will take away potential funds to help repair some of the state’s deteriorating roads and bridges. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, Pennsylvania has the second-highest number of structurally deficient bridges (9,561) among the 50 states, and 57 percent of its roads are in mediocre or poor condition.

“The Mon/Fayette Expressway is an extremely expensive pork-barrel project that will rip apart communities to provide access to a sparsely populated part of the state,” wrote Schweiger in a statement to CP. “This boondoggle will saddle the motoring public statewide with the bill when … fuel taxes could be better served repairing failing bridges and crumbling roadways. Let’s fix the problems that we have before building more highways.”