About 3 p.m. on Dec. 20, 2006, a block from Westinghouse High School, someone fired a .22-caliber bullet that entered the upper back of 17-year-old James Stubbs, lodged in his neck and took his life. Stubbs was the lone victim of an apparent gun battle that left Homewood’s North Lang Street and Fuchsia Way littered with shell casings.

Nearly two years later, on Nov. 17, 2008, a jury concluded that Stubbs’ killer was Joseph Hall, of Penn Hills, who at the time of the shooting was a 17-year-old sophomore at Allderdice High School. Hall, who was tried as an adult, is now in state prison, serving a sentence of 17½ to 35 years for third-degree murder and unlawful possession of firearms.

But 10 years after the shooting, a review of court records by City Paper suggests that the case against Hall is shaky at best. His procession through the court system was a bizarre one, including two mistrials. But the key points are these:

- The state produced no physical evidence placing Hall at the scene of the crime, nor was a murder weapon ever found.

- The lone witness to the shooting who testified changed his story several times, and during the criminal trial ultimately recanted earlier sworn testimony identifying Hall as the shooter. At least one part of this witness’ story implicating Hall is verifiably false.

- The only other eyewitness placing Hall at the scene of the shooting has a questionable story. Several witnesses whose testimony might have exculpated Hall — including one eyewitness to Stubbs’ shooting — never testified at the trial.

Hall has consistently maintained his innocence. The inconsistencies and lack of evidence in the case against him led to an investigation by Point Park University’s Innocence Institute; a 2010 article in the group’s magazine, Justice, focused on the key witness’ lies. Hall’s case has also drawn the attention of Human Rights Watch and local activist groups including 1Hood. 1Hood’s Paradise Gray calls Hall’s conviction “a blatant railroad case.”

But Hall’s conviction has survived several appeals, and his lawyers have exhausted every possible appeal at the state level. This past summer, Hall retained a new attorney, Robert Stewart, who is exploring possible action in federal court. At press time, the likelihood of such a filing seems strong; as Stewart’s paralegal, Megan Dancey, puts it, “Things don’t add up in this case.”

"I went home to him, I hugged him. 'Cause the feeling just prior of thinking he was dead was overwhelming."

tweet this

In the minutes following the shooting of James Stubbs, police first heard Joseph Hall’s name for a reason that was deeply ironic: Hall’s mother, worried that it was her son who was the victim, gave it to them.

Cecilia Coleman, then 36, lived in Penn Hills and worked in a Lawrenceville warehouse, disassembling computers for Allegheny County government. On Dec. 20, 2006, she was at work when a friend called and said, “Little J got shot.”

“Little J” was a nickname for her son. Coleman got in her car and sped toward Homewood.

The shooting had ended, the area mostly clear except for police.

“I go to the crime scene, the young man’s body was already moved,” Coleman says. “There was a gold Carhartt coat still on the ground with blood, with casing shells still around. And I was crying, asking the officers, ‘Where did y’all take that young man, that’s my son, Little J.’ And they said, ‘Little J? What’s your son[’s name]?’ and I said, ‘Joseph Hall.’”

Coleman says the officer replied, “I don’t think that’s the young man’s name, but they do call him Little J.” And he said, “This young man’s 17.”

“And I said, ‘So’s my son, he’s 17.’ … And then as they was taking my information down, they said, ‘Here’s a card. Give us a call.’ I said, ‘Well, I’m going to the hospital, what hospital they transfer him to?’ I was just thinking, ‘My son got shot in the head.’”

But Joseph Hall had not been shot.

“As I’m headed to the hospital, I get a call from my son, in Penn Hills, at home,” says Coleman. “And it’s like, ‘Mom, what’s going on? People’s calling me talkin’ ’bout — ’” Word of the shooting had spread. “And I was like, ‘Jo Jo?’ I almost crashed. I said, ‘Oh my goodness. They said Little J’s 17, down here dead, got shot in the head, thinking it was you.’ …

“I went home to him, I hugged him. ’Cause the feeling just prior of thinking he was dead was overwhelming.”

For Coleman, and for Joseph Hall, however, the story was really just beginning.

In Hall’s telling, as related in a recent interview, he’d spent the morning of Dec. 20 at school before being sent home around noon, for fighting. Later in the afternoon, he drove himself to a local convenience store where he saw some friends, then gave one of them a ride to work before returning home. At about 5 p.m., two friends arrived. One was Lamont Hall (no relation), 18, whom he’d known for a few years. The other was Allen Strothers, 19, a life-long friend of Lamont Hall’s whom Joseph Hall had met more recently. Joseph Hall says the two excitedly told him they had just driven through a rain of bullets near Westinghouse. Then, as they watched the TV news, a report came on about the shooting near Westinghouse that placed a blue Kia at the scene, one just like Strothers’. Strothers panicked: He called 911 to report that his car had been stolen earlier that day — before the shooting, in other words — but that he had just recovered it.

But Strothers’ 911 call served only to put him on law enforcement’s radar. Police arranged to meet him. And that evening, during an interview with detectives, Strothers audio-recorded a statement that placed both Joseph Hall and Lamont Hall in the Kia near Westinghouse that day. They had driven there, Strothers said, intending to pick up girls. But he said the jaunt ended with both Joseph and Lamont wielding guns and firing out the window during a gun battle on the stretch of North Lang Street where James Stubbs was killed.

In the two years that followed, Strothers’ story would change drastically several times, even during testimony he gave under oath; ultimately, during the 2008 criminal trial, he said that Joseph Hall hadn’t been in his car at all that day, that no one had fired guns from his car, and that police had coerced those earlier statements to the contrary. But it was that first statement recorded by detectives on Dec. 20, 2006 (along with a second recording made two weeks later), that would form the bulk of the case against Joseph Hall.

In the days following the shooting, however, something else happened that would come to cast a shadow over Hall’s claims of innocence. First, he and his mother learned via TV news that he was wanted by police. Then, on Dec. 26, at his mother’s urging — she says she feared for her son’s life if police came after someone whom they had labeled “armed and dangerous” — Hall fled Pittsburgh for Indianapolis, Ind., where he stayed with Coleman’s brother. On Jan. 2, Hall was arrested by Indianapolis police and transported back to Allegheny County Jail, where he’d spend most of the next two years awaiting trial.

Hall would plead not guilty to the charges of first-degree murder, criminal conspiracy and illegal possession of firearms. (He was tried alongside Lamont Hall, who also pleaded not guilty to the same charges.) While he did not testify at his own trial, Joseph Hall has subsequently maintained that he had seen neither Strothers nor Lamont Hall that day until they turned up at his house nearly two hours after the shooting. But splitting town while he was wanted came to look like an unwise move — especially at his trial, when the prosecutor recounted the episode to the jury. Hall’s flight from Pittsburgh couldn’t have helped him either with Judge David Cashman, who in sentencing Hall would call Stubbs’ murder “a designed, deliberate and cold-blooded execution.”

Hall was born in 1989 and grew up in Lincoln-Lemington. Though undersized, at about 5’4”, he played sports, including football on a community team in Homewood, the neighborhood his father was from. (His legal residence in 2006 was his father’s place, in East Hills, allowing him to attend Allderdice.) Hall sang in the boys’ choir at the Afro American Music Institute, which Coleman’s parents founded in 1982. Though he was literally a choir boy, he did have a penchant for getting in scraps at school, behavior his mother attributes to his small stature.

More than two years elapsed between his arrest and his sentencing, time Hall spent in Allegheny County Jail. Since then, he’s been incarcerated in state prison — SCI-Forest, in Marienville, located on a site carved out of the woods of Forest County, about 100 miles north of Pittsburgh. In September, he turned 27.

At the time of the shooting, a young woman Hall knew was pregnant; she gave birth to their daughter on Valentine’s Day 2007. Hall’s daughter, 9, has seen him only in prison. His main point of contact on the outside remains his mother, whom he phones daily.

Hall and a cellmate share a 9-by-12-foot cell. In an interview with City Paper at SCI Forest in August, Hall said he spends his time one of three ways: talking to his family by phone; working out; and researching his case. The latter activity constitutes close to a full-time job, four or five hours a day reading through court documents and making detailed typed or handwritten notes about inconsistencies and inaccuracies in the case against him. Working for his freedom, he says, is “the only way I stay sane.”

“I don’t get discouraged,” he says.

Joseph Hall acknowledges that he was friends with both Lamont Hall and Allen Strothers; on many days, they did drive to Westinghouse as school was letting out to check out girls. He acknowledges that he got in fights in school; he also spent some time in the county’s Shuman Juvenile Detention Center. But he says that was the extent of his misbehavior. He says the only firearms he ever shot were paintball and BB guns. And he says he definitely wasn’t in Strothers’ car on Dec. 20, 2006. Hall has recalled watching in disbelief as the jury pronounced the verdict against him. “I just thought, ‘Is this happening? Can this happen?” he told reporters for the Innocence Institute in 2010.

Perhaps the thing that baffles Hall most about the case is the lack of physical evidence linking him to the scene, especially the absence of shell casings from the .22 he was supposedly firing.

Coleman, who is wont to describe herself as “feisty,” is as consumed by her son’s case as he is. She has been notably proactive in her son’s defense; at one point, her efforts led to a grand-jury hearing about possible obstruction of justice. To date, she tells CP, she has spent “at least $30,000” on her son’s defense and appeals. They’re now on their third lawyer. “It’s really financially, mentally draining for me,” she says; her key supporters on both fronts are her parents, James Johnson and Pamela Johnson, AAMI’s founders and Joseph’s grandparents.

Coleman says that her experience with her son’s case has disillusioned her. She says that his conviction despite the lack of evidence has convinced her the courts are corrupt. “I have no faith in the judicial system,” she says. “I never realized how wicked and unethical it was.”

But it’s to the judicial system that Hall must continue appealing. After the possibilities for appeal at the state level were exhausted, Coleman sought the services of attorney Robert Stewart, with offices in Downtown Pittsburgh. Stewart’s paralegal, Megan Dancey, recalls that like most people with a legal problem, Coleman told her, “There’s something wrong with my case.”

But the more Dancey looked into it, the more there really did seem to be problems. “‘But this is weird. This is weird,’” Dancey recalls thinking about the case. “And it started getting stranger and stranger.”

"We all knew nobody shot nobody. We know that for sure."

tweet this

Even before his trial began, Joseph Hall’s case was full of odd turns.

It starts with Allen Strothers, driver of the blue Kia. According to transcripts of his two audio-taped interviews with detectives after the shooting, Strothers had told police that he had driven Lamont Hall and Joseph Hall to Westinghouse to pick up girls, and had unexpectedly ended up in gunfire. In the second tape, recorded Jan. 4, 2007, Strothers provided a more detailed story. He said that after the shooting, the three drove to Joseph Hall’s house, where Joseph Hall stripped off his shirt and dropped to the floor to do push-ups to celebrate shooting Stubbs.

In various versions of the story that Strothers would tell in the two years between the shooting and the trial, some aspects were fairly consistent: He drove to Westinghouse. He parked the Kia at curbside and was asked by a Pittsburgh Schools Police officer to turn down his car stereo. He then drove past a particular alley off North Lang where one or more men on foot were acting threateningly toward the occupants of his car, and gunfire ensued.

But those first two recordings are full of inconsistencies as well. For instance, Strothers says he was driving the two Halls that day because he was the only one of the three who had a car — even though in reality, Joseph Hall owned a car. In the first tape, Strothers describes Joseph Hall shooting a .22 Ruger rifle; in the second tape, it’s a Ruger handgun. Moreover, Strothers describes Hall emptying at least one full clip and part of a second from a .22 Ruger with his arm extended outside the car window. But no .22 shells were found at the scene, save the one that killed Stubbs. By contrast, North Lang was strewn with eight .40 shells, of the sort that would have come from the Glock that Strothers said Lamont Hall was firing with his arm similarly extended out the window. (Police also recovered four spent .9 mm shells and two live .9s, presumably from guns being fired by people standing in the street.)

At a preliminary hearing in January 2007, more inconsistencies emerged. For instance, Strothers first said that both he and his two passengers that afternoon had exited the car at one point before the shooting. Moments later in his testimony, however, Strothers said that Joseph Hall “never got out.” Strothers said he then drove his car past an intersection where men on foot had guns and were acting threateningly, but his explanation as to why he nonetheless then circled the car back past the very same intersection is vague (something about not wanting “to go too deep into Homewood”). And he repeatedly changed the number of people he said he saw on the street, ranging from just the one guy in fatigues to “all these Homewood dudes in the alleyway.”

Moreover, it’s often unclear from Strothers’ testimony who supposedly shot first during the melee. He described his car making a pair of passes on North Lang. Initially, he told prosecutor Mark Tranquilli that, after the three of them saw men on the street pull guns during the first time the car circled the block, Joseph Hall fired first, as a warning shot, into the air. The second time the Kia circled the block, Strothers told Tranquilli, “all these Homewood dudes” shot at the car, and Joseph shot back (with Lamont Hall firing into the air). But minutes later at the hearing, during defense attorney T. Brent McCune’s cross-examination — and after much back and forth about who shot first — McCune asked, “Were there shots going at you before Joe fired his first shot?” and Strothers replied “Uh-huh.” Later still, asked by Tranquilli to list the order of shooters and using his friends’ nicknames, Strothers said, “Dro [Joseph], Homewood, then Dro, then Monty [Lamont].” But asked again shortly afterward who shot first, he said, “Homewood.” “All right,” said Tranquilli at one point. “You have testified now two different ways. Explain it again.”

Strothers, however, did testify consistently that he saw neither Joseph Hall nor Lamont Hall point a gun at anyone, and that he never saw anyone actually get shot. On describing Joseph Hall first firing, in fact, Strothers says it was as a warning shot, aimed “in the sky”; Strothers also describes Lamont Hall firing only warning shots in the air. And at the preliminary hearing, Strothers added, “We all knew nobody shot nobody. We know that for sure.”

This was the core of the pretrial testimony that got Joseph Hall and Lamont Hall held for trial on murder charges.

Also curiously, Strothers testified that he went with Lamont Hall to the store at 10 a.m., met Joseph Hall there, then decided to go to Westinghouse, all without Strothers explaining — or any lawyer asking him to explain — what else, aside from an unsuccessful attempt to buy weed, they did in the five hours that elapsed between 10 a.m. and the shooting at 3 p.m. Moreover, school records since obtained by Cecilia Coleman demonstrate that her son was in school that morning before being sent home at about noon for a fighting incident — meaning that Hall couldn’t have seen Strothers until the afternoon at the earliest.

The preliminary hearing complete, another turn of events arrived in November 2007. While Hall was in jail awaiting trial based on Strothers’ statements, Strothers approached Coleman at her home to say that his taped statements to police had been made under duress, and were lies: Joseph Hall, Strothers now said, hadn’t even been in the car with he and Lamont Hall. And then Strothers, with Coleman present, recorded a short videotaped statement to that effect. A second videotaped recantation followed two days later, this one made at her workplace, the Afro American Music Institute.

The appearance of the videotapes resulted, in January 2008, in the convening of a grand jury to determine whether Coleman had engaged in obstruction of justice. There, Strothers took the stand and, contradicting his recent videotaped statements, repeated the story he’d first recorded for police: that both Halls had been in the car with him, shooting out the window. He told the grand jury that he had made the videotapes because he wanted to avoid being thought a snitch on the street.

But that was far from the final twist in the case.

In June 2008, a criminal trial began, but Judge David Cashman declared a mistrial after a prosecution witness, Pittsburgh Public Schools Police Cmdr. Joseph Garrett, suffered a stroke on the stand and had to be carried from the courtroom. (Garrett died soon after.) In August, a second mistrial followed when police officer George Edwards, a scheduled witness, was unavailable to testify because he was on vacation.

The third attempt at a trial was preceded by an October 2008 evidentiary hearing that generated further controversy. McCune, Joseph Hall’s defense attorney, sought permission to hear testimony from Talib Kevin Ghafoor, a veteran police officer who’d said that just after the shooting, another cop (who happened to be George Edwards) had told Ghafoor that he’d heard that the man who shot Stubbs was on foot, not in a car. However, Edwards himself testified that he had been talking to Ghafoor about another case. Then, after prosecutors produced audio recordings of Ghafoor speaking to Joseph Hall in prison by phone, Ghafoor admitted that he was “aligned” with the defendants. (Ghafoor resigned from the police force shortly thereafter.)

At the same evidentiary hearing, Judge Cashman also disallowed the defense’s attempt to introduce testimony from a Homewood woman who claimed that another man, named Nitty, had told her that it was he who had shot Stubbs.

The trial began Nov. 6. The prosecutor was experienced assistant district attorney Daniel Fitzsimmons. McCune, whom Coleman had found to represent her son in 2006 through the office of lawyer Jim Eckert, was a former assistant district attorney who’d gone into private practice earlier that year.

The trial commenced on what sounded like promising notes for Joseph Hall. In his opening statement, Fitzsimmons acknowledged the absence of physical evidence linking Hall to the crime, saying, “There is not going to be what you might call a CSI moment.” He also told the jury that Strothers was the crucial lone witness who would testify, but even so noted Strothers’ history of changing his story. Jurors listening to Strothers, he said, would be in the business of “judging his credibility.”

Strothers, who worked detailing cars, had moved to Cincinnati temporarily after the shooting as part of the witness-protection program. Jurors were told that he had been granted immunity from prosecution in exchange for his testimony, and his testimony was indeed the highlight of the 11-day trial. But not in the way prosecutors hoped.

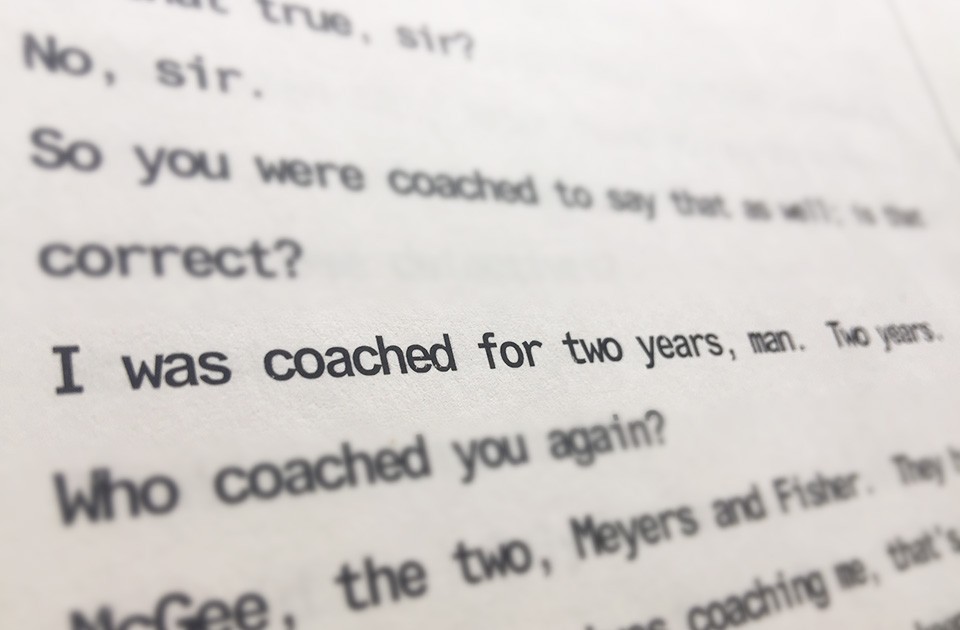

First, according to the trial transcript, Fitzsimmons reminded Strothers what “immunity” means, and what it had meant when he testified before the grand jury: that “pretty much the only way you can get in trouble here today is if you lie.” Strothers said he understood.

Then Fitzsimmons asked, “Now on December 20, 2006, were you present with Joseph and Lamont Hall when some shots were fired down on North Lang Avenue in the City of Pittsburgh, sir?”

[Strothers]: No. I was present only with Monty.

[Fitzsimmons]: Excuse me?

A: I was only present with Monty, Lamont Hall.

Q: Did you testify about these same matters in front of that same grand jury that we are talking about?

A: Yes, I did. Been coached the whole time.

From there on, Strothers stuck to this story: that from his first interview with detectives William Fisher and Joseph Meyers, on the night of the shooting, a series of detectives “coached” him to place Joseph Hall in the Kia, a loaded gun in his hand, firing out the window. “Today I’m not lying for detectives no more,” Strothers insisted, a stance he maintained even after Judge Cashman threatened to jail him for lying.

Strothers testified there were no weapons in his car that day. He said the only reason he ever said otherwise was that detectives threatened him with 20 years in prison if he didn’t describe the story the way they wanted. And he said that those first two taped statements came out as they did because detectives kept recording over earlier statements he made until he got it just as they had coached him to say. He added that he had fabricated details — like Joseph Hall removing his shirt and doing push-ups to celebrate the shooting — to please police.

At times during the trial, Strothers was combative. At one point, when Fitzsimmon asked about an earlier statement he’d made, Strothers responded, “I don’t have to answer that question like you want.”

Fitzsimmons also asked Strothers about his grand-jury testimony, when Strothers had said that the videotaped statements recanting his earlier testimony were themselves lies. But now Strothers stayed with his new story, which was that it was his grand-jury statements that were the lies.

[Fitzsimmons]: Sir, you never told the grand jury anything even close to what you told this jury?

[Strothers]: I know.

Q: You never told that jury that Joseph Hall was not there that day, did you?

A: I know.

Fitzsimmons also brought up an informal 2007 meeting that Strothers had arranged with Lamont Hall’s lawyer, Patrick Thomassey, ostensibly to tell Thomassey that Joseph Hall and Lamont Hall were innocent; but at that meeting, held at an Eat ’N Park restaurant, Strothers now acknowledged on the stand, he had instead reiterated that they were guilty.

When the lawyers had finished questioning Strothers, Judge Cashman ordered the witness removed and in contempt of court. (“He acknowledged he committed perjury, I’m just not sure where,” Cashman later told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.)

Strothers, however, was never charged with contempt.

How likely is it that Allen Strothers’ testimony implicating Joseph Hall was coerced by police, who he said “coached” him on details of the crime?

Experts say far too many convictions result from statements from people with incentives to testify — incentives including reduced prison time for themselves.

Most commonly, allegations of coerced confessions are made by criminal suspects, says University of Pittsburgh law professor David Harris, an expert on police behavior and criminal justice.

That’s happened in numerous high-profile instances, including that of the Central Park Five, the infamous 1989 rape case in New York City. Five youths confessed to the assault on a lone jogger in Central Park, but later recanted, claiming the confessions were coerced during lengthy police interrogations. The youths were convicted even though none of the DNA recovered at the crime scene matched theirs. They had all served out their sentences before DNA evidence, and a serial rapist’s confession to the crime, resulted in those sentences being vacated in 2002.

Testimony from police informants, jailhouse snitches and other non-suspects who have been threatened with prosecution (or offered the prospect of less jail time) are also a major source of wrongful convictions, Harris says. “Much of this testimony turns out to be quite unreliable,” he adds. “Sometimes you might have people coerced just because the police need a witness.”

“In 15 percent of wrongful conviction cases overturned through DNA testing, statements from people with incentives to testify … were critical evidence used to convict an innocent person,” according to the Innocence Project, a New York, N.Y.-based nonprofit that works to exonerate the wrongfully convicted through DNA evidence.

The Innocence Project cites, among others, the case of Wilton Dedge, who was sentenced to two concurrent life sentences in the 1981 rape and assault of a Florida woman. Prosecutors hung part of their case on the testimony of Clarence Zacke, a jailhouse snitch whose sentence was greatly reduced at the time of Dedge’s trial; Zacke claimed that Dedge had confessed the crime to him. DNA evidence exonerated Dedge in 2004, after he’d served 22 years in prison.

In many such cases, deals with witnesses are not disclosed to juries, says Harris. At Joseph Hall’s trial, the jury was told that Strothers had been granted immunity from prosecution in exchange for his testimony. But only Strothers himself claimed, in his dramatic recantation on the stand, that police had told him that as an accomplice to the shooting he faced 20 years in prison if he didn’t implicate Joseph Hall.

Strothers did not respond to messages from City Paper seeking further comment. But obviously, to be offered reduced jail time in exchange for testimony is “a very powerful motivator,” says Harris.

In such deals, Harris says, informants can also be encouraged to provide details the police want to hear, even to the point of making them up. This is what Strothers claims happened with, among other details, the scene of Joseph Hall celebrating Stubbs’ shooting.

But informants, like any other witness, don’t serve a case well if they can’t keep their stories straight. Presented with the narrative of Strothers’ multiple versions of what happened on Dec. 20, 2006, Harris said, “This guy reversed himself so many times that his credibility would be shot.”

"[I]f he did nothing to involve himself in the commission of the crime, why would he flee?"

tweet this

At the criminal trial of Joseph Hall and Lamont Hall, detectives denied that they had coerced Strothers, coached him or recorded over statements he’d made. However, while testimony from forensic experts placed Strothers and possibly Lamont Hall in Strothers’ Kia, no fingerprints or DNA evidence found anywhere in the car — including the rear passenger seat, where Joseph Hall was supposedly sitting — implicated Joseph Hall. Indeed, technicians found gunfire residue on the right hand of the victim, James Stubbs, indicating that he had shot a gun that day. But the only evidence that Joseph Hall had even held a gun was the say-so (later recanted) of Strothers.

One other witness, however, did place Joseph Hall at the scene. Stephen Shaulis, who on Dec. 20, 2006, was working as a Pittsburgh Public Schools police officer, testified that he had glimpsed Hall in the blue Kia that day and recognized him from an incident at Allderdice a month before the shooting — a fight after which he had handcuffed Hall. But Hall today says he never saw Shaulis before the trial. And several factors make Shaulis’ testimony appear questionable.

One, Shaulis was not subpoenaed until 2008 — only after the prosecution’s original witness from the Schools Police, Cmdr. Garrett, suffered a stroke on the stand, and some 18 months after both the shooting and the incident at Allderdice. And two, Shaulis’ testimony placed Joseph Hall in the front passenger seat of Strothers’ car, whereas Strothers had consistently placed him in the rear.

Two alibi witnesses testified for Joseph Hall. Whitney Felder and Brandyn Elston were friends of Hall’s, both 17 at the time of the shooting. Felder testified that she had seen Hall at the Get-Go on Frankstown Avenue just before 3 p.m. on the day of the shooting, while she was waiting for her bus. Elston testified that he had gotten out of school at 2:30 p.m. and run into Hall at the Get-Go, and that Hall drove him to work at Long John Silver’s, on Rodi Road, where he arrived in time for his 4 p.m. shift.

The trial wound down. In his closing argument, McCune emphasized that “[a]ll of the Commonwealth’s case comes from the mouth of one person” — Allen Strothers, whom McCune described as an “accomplice witness,” or one who can’t be trusted because he was too involved in the alleged criminal act. And that’s in addition to Strothers’ general inconsistency: “The only thing you have heard is Allen Strothers give one unreliable statement after another.”

Fitzsimmons, by contrast, had to convince the jury that only Strothers’ statements implicating Hall were true. The prosecutor recalled a statement Strothers had made on the Jan. 4, 2007, recording with police, indicating that Joseph Hall had a beef with James Stubbs, and suggested to the jury that the shooting was “perhaps a turf war between young men in one neighborhood and young men in another neighborhood.”

The prosecutor also noted Hall’s flight to Indianapolis after the shooting. That journey two years earlier had been initiated by Coleman, who recalls today: “I’m nervous because I know they got him on the news, ‘armed and dangerous.’ Young black man. I knew they [police] would kill my baby. … I talked to my brother, said, ‘Please come get him until we get a lawyer. This is my only child, my son.’” (Coleman says that it was hard to get a lawyer quickly because it was so near the holidays.) But in his closing argument, Fitzsimmons merely summed up: “[I]f he did nothing to involve himself in the commission of the crime, why would he flee?”

And Fitzsimmons argued for the credibility of Strothers’ original statement to police implicating Hall by noting that, just hours after the shooting, Strothers had identified the gun he said Hall had fired as a .22-caliber Ruger. How, Fitzsimmons asked the jury, could police have fed Strothers such a detail that evening, just hours after the shooting, and hours before the autopsy was even conducted?

The latter point seems to have been of particular interest to the jury. During deliberations, its requests to Judge Cashman for further information included the date and time of the coroner’s report, and the time that the bullet was removed and tested. Cashman granted the jury’s request to again hear Strothers’ taped statements to police — the ones implicating Joseph Hall. But on the other questions, the judge instructed the jury to “use your individual and collective memories.” (In fact, the trial transcript contains no mention of the time that the bullet was removed for testing. The official autopsy report — which indicates that the autopsy was conducted at 9:23 a.m. on Dec. 23, some 12 hours after Strothers recorded his first statement for police — implies that the bullet was extracted at that time, and not earlier. That lessens the likelihood that police could have told Strothers the caliber — though of course it doesn’t speak to who actually fired the .22-caliber gun.)

The jury deliberated for more than a day before finding Joseph Hall guilty of third-degree murder and illegal possession of firearms. Lamont Hall was found guilty of only the latter charge and sentenced to two to four years.

Joseph Hall was sentenced in February 2009. “You went there to execute Mr. Stubbs,” Cashman told him, before levying a sentence of between 17½ and 35 years.

The sentencing was also the stage for Stubbs’ parents to express their grief and anger. “I miss my son dearly,” said his mother, Nancy Zanders-Stubbs, according to a Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article. She told the court she’d suffered three strokes since the killing. “He was good to me. He took care of me. And now I have to deal with this.”

Stubbs’ father, James Stubbs, expressed bafflement at the friends and family members who had testified at the sentencing on behalf of Hall’s character. “If it was all like that, why are we all here?” said Stubbs. “Why is my son in the ground?”

At the sentencing, Hall expressed sadness over Stubbs’ death. But he also said, “Even though I was charged and convicted, I am truly innocent.”

Within two weeks, Hall had filed a motion for reconsideration of the sentence. The appeal, argued in a courtroom populated by activists from groups including Human Rights Watch, was rejected. In 2010, Judge Cashman rejected a direct appeal as “meritless.” Hall’s new attorney, Paul Gettleman, also appealed to the state Supreme Court, which upheld the conviction and sentence.

In 2012, Gettleman filed an indirect appeal under the state’s Post-Conviction Relief Act, alleging ineffective assistance of counsel on the part of defense attorney Brent McCune. At a July 2013 hearing on the appeal — nearly five years after the trial — Gettleman cross-examined McCune about several aspects of his defense strategy for Joseph Hall.

One line of questioning involved Stephen Shaulis, the school-police officer who testified he’d seen Hall at the scene of the shooting. Under questioning, McCune acknowledged that Shaulis’ testimony, that he knew Hall from an earlier incident at Allderdice, was a “surprise” that arose during the trial. But McCune said that he didn’t think to request a continuance on this crucial bit of “late discovery” evidence, to allow further investigation of the claim. “In hindsight maybe I should have done that,” McCune said. “So much stuff is swirling in your head. … It didn’t occur to me.” (However, later in the hearing, the assistant district attorney established that McCune had in fact filed a motion objecting to Shaulis’ testimony, but that it was denied.)

Asked whether he had investigated Shaulis’ claim to know Hall from the prior incident at Allderdice, McCune said, “I made some phone calls on it” but “I remember it not panning out.” McCune also admitted that he didn’t press Shaulis for details about the incident at the school, including who else might have been present.

Gettleman also questioned McCune about the fact that Joseph Hall never testified on his own behalf. “I was concerned that under cross-examination he’d get tripped up. I didn’t think it was necessary for him to take the stand,” said McCune. The defense attorney said he believed there were enough alibi witnesses, and besides, “I didn’t want Fitzsimmons having a crack at him.”

Today, Joseph Hall deeply regrets that he did not testify at his trial. He wanted to, he says, but McCune convinced him and Coleman that he shouldn’t, and Hall backed down. (Co-defendant Lamont Hall also did not testify at the trial.) Now Joseph Hall believes that not testifying made him look guilty, and that if he had testified it would only have helped him. As to McCune’s concern that Joseph Hall might be tripped up on the stand, Hall says, “You don’t have to be afraid of being tripped up if you’re telling exactly what you know.”

Also at that July 2013 hearing, Gettleman questioned McCune about a letter written by Lamont Hall from jail, in which the co-defendant stated that Joseph Hall had in fact not been at the scene of the shooting, and that the police had threatened him with life in prison unless he said so. Lamont Hall wrote, in part, that the police “threaten[ed] me into putting Joe Hall on the scene of the crime, and saying he shot James Stubbs. … They also told me that they would let me go free if I lied on Joe Hall and say I saw the [w]hole thing …”

Gettleman asked McCune why he never brought the letter to the court’s attention or made a motion to sever Joseph Hall’s case from Lamont Hall’s, so that the latter might testify on the former’s behalf. “I didn’t think of that,” responded McCune. (Lamont Hall died in December 2014, the victim of a shooting in Lincoln-Lemington.)

Another line of questioning concerned McCune’s odd attempt, during the trial, to argue, essentially, that Hall was never at the scene of the shooting — but that if he was there and did shoot, it was in self-defense. (The latter argument was predicated on the fact that Stubbs had gunpowder residue on his right hand, indicating he was shooting too.) McCune’s idea was that if the jury didn’t believe Hall’s alibi defense, the “justification” defense could still get him a lesser sentence; at the PCRA hearing, the defense attorney described it as a “cake-and-eat-it-too position.” At trial, Cashman had refused to let McCune simultaneously pursue the two seemingly contradictory defenses. But now, Gettleman pressed McCune on why he didn’t object to Cashman’s failure to inform the jury that it could still acquit Hall even if they disbelieved the alibi. “Could it be something that you just missed?” Gettleman asked. “Might have been,” McCune replied.

Hall’s PCRA appeal also objected that McCune had wrongly told Hall’s family members that they couldn’t attend jury selection.

The appeal did not note that Hall appears to have spent the morning of Dec. 20 at Allderdice — contradicting Strother’s incriminating story that he had met him at the convenience store that day just after 10 a.m. Today, Hall says he told McCune he was at school that morning, but the defense attorney never brought up this fact at trial.

Under questioning by Gettleman, McCune also acknowledged that during “an emotional moment” after Hall had been convicted, McCune had said to Hall’s family, “Maybe you guys can file an ineffective [counsel] petition, maybe I did something wrong.”

McCune did not return messages seeking comment for this article.

Appeals based on ineffective counsel are notoriously difficult. “Those are just achingly hard to win,” says David Harris, the Pitt law professor. Under the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Strickland v. Washington, the appellant must prove not only that his attorney erred, but that the errors resulted in an unfair trial. “It’s a very high standard,” says Harris.

Hall’s PCRA appeal went nowhere. In March 2014, Allegheny Court of Common Pleas denied it. Hall appealed this decision to the Superior Court of Pennsylvania, which in October 2015 affirmed the lower court’s ruling. Superior Court held that while McCune had erred in telling Hall’s family members that they were not allowed in the courtroom during jury selection, nothing he had done or failed to do would have changed the outcome of the case.

For instance, the court ruled that the phone calls McCune made about Shaulis’ testimony constituted an adequate investigation. While McCune failed to seek to sever Joseph Hall’s case from Lamont Hall’s, the court found that Joseph Hall was unable to prove that Lamont would actually have testified. On the objection that McCune had prevented Joseph Hall from testifying, the court cited two colloquies that Cashman had held with Joseph Hall, in which the defendant said he understood that the decision whether to testify was his alone, and not McCune’s. And Superior Court held that McCune couldn’t be blamed for “failing to renew an objection to the trial court’s refusal to give jury instructions on voluntary manslaughter and justification” after the court had already told him he couldn’t make both arguments.

This past June, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania refused to hear an appeal of the Superior Court’s decision. That left Hall with no further options at the state level.

This year, Hall dropped Gettleman and retained Downtown attorney Robert Stewart. Hall’s hopes now might rest largely on convincing a federal judge that evidence that was not introduced in his criminal trial would have made a difference.

That, says David Harris, the University of Pittsburgh law professor, is also a challenging path. “With every step through the appeal process,” says Harris, “your odds get longer.”

As Joseph Hall and his attorney prepare to make his case anew in federal court, perhaps the most important witness is one who has yet to testify under oath.

At the trial, James McGee, the veteran Pittsburgh Police detective who investigated the murder, testified about a man named Stephen M. Bradshaw, who lived in an apartment building near the corner where the shooting happened.

According to a police report dated Dec. 20, 2006 — and filed by officer Dale Canofari, who had interviewed Bradshaw — Bradshaw said he heard shots from inside his apartment and went out the back door to see what was happening. He said “he noticed 5 or 6 people come out of Fletcher Way onto N. Lang from the west side of N. Lang” and then heard more shots as a “small blue and green” car passed by those people. “Bradshaw said the shots came from the car but he could not say from what window.” After hearing the second set of shots, “Bradshaw said he ran into his house and stayed inside.”

At trial, McGee told the jury that Bradshaw had been subpoenaed but was now living “somewhere in North Carolina” and that attempts to reach him had failed.

The matter got no further in court. But some seven years later, Joseph Hall ran across the police report quoting Bradshaw. Cecilia Coleman tracked him down, and Bradshaw has since supplied a written account of the shooting which differs from the police report.

This account adds that Bradshaw saw one man, on foot, chasing and shooting a second man in a tan coat — the same color coat that Stubbs wore. Bradshaw wrote to Coleman that although he had provided this account to a detective, he “was never contacted after the interview, either by detectives and/or an attorney.”

City Paper’s attempts to reach Bradshaw were unsuccessful.

Coleman says that the handling of Bradshaw by the courts only deepens her distrust of the criminal-justice system. “They didn’t want to find him!” alleges Coleman. Now that he’s been found, however, “I don’t want to get my hopes up too high,” she said earlier this year. “I been disappointed through a whole decade.”

Coleman and Hall also say there is new evidence casting doubt on testimony from another key witness at the criminal trial: Stephen Shaulis, the Pittsburgh Public Schools officer who also placed Hall at the scene of the shooting. They say they have located one or more witnesses from his November 2006 fighting incident at Allderdice who will testify that Shaulis wasn’t actually involved. Such testimony would corroborate Hall’s assertion that until the trial, he’d never encountered Shaulis, and that he wasn’t handcuffed after that incident — a routine scuffle with another student over a girl, he says. This issue was among those raised in Hall’s appeals based on claims of ineffective assistance of counsel. Megan Dancey, the paralegal for Hall’s current lawyer, agrees that this part of the case could use more work. “I just feel like there could have been a little more investigation done,” she says.

Coleman also says there were additional alibi witnesses not called in the 2008 trial who could place her son at her home on the afternoon of the shooting.

Appeals at the federal level are not high-percentage plays. One common option for convicted felons is to petition the court for a writ of habeas corpus to potentially overturn the conviction. That normally requires demonstrating that some Constitutional right was violated, such as if prosecutors withheld evidence, or defense counsel was ineffective. If there is new evidence, such as a new witness, the appellant would likely have to introduce it in a new appeal to the state courts, says Marissa B. Bluestine, legal director of the Pennsylvania Innocence Project. But Bluestine says such appeals are difficult to win.

In 2008, Coleman and friends including 1Hood’s Paradise Gray founded MACOTI — Mothers Against Conviction of the Innocent. She uses the group’s Facebook page to raise awareness about her son’s case and other criminal-justice issues. Coleman says she feels hopeful about her son’s new lawyer and other recent developments in his case.

Joseph Hall is hopeful, too. But after 10 years, he also doesn’t want to get his expectations too high.

In a phone call from prison early in December, Hall expressed hope that his new attorney will do at the federal level what his previous attorney could not at the state level.

“We’re making progress,” he said. “There’s some momentum going on right now.”