Well, this is it. If you've been waiting for a date by which we must act to have any hope of preventing the worst effects of climate change, your answer is here. And the answer is, pretty much, today.

Last June, NASA's chief climate scientist, James Hansen, told Congress that unless we seriously address this problem in 2009, "disastrous climate changes that spiral dynamically out of humanity's control" are probably inevitable.

Hansen is the guy who, in 1988, told Congress that man-made global warming had begun. Most of us didn't listen then. But we'd be wise to now. Because by "disastrous," Hansen means floods, droughts, food shortages, millions of refugees. For starters.

Some of this might be years away, but some of it's already happening. And it could get much worse very soon.

Leading the world away from such a fate will require "transformative change of direction in Washington," said Hansen, speaking in the midst of the 2008 presidential campaign.

Now, after eight years of a White House that actually suppressed scientific information about global warming, our president-elect ranks climate change as "one of the biggest challenges of our times." Barack Obama promises to cut the country's greenhouse-gas emissions 80 percent by 2050 -- the reduction that most scientists say can avoid the worst possible outcomes.

Yet critics question whether Obama's urgency matches his rhetoric. Almost by necessity, with banks failing and joblessness rising, the campaign fixated on the floundering economy rather than the possibility of climate apocalypse.

Worse, lately some climate-change experts scan Obama's very ambitious carbon-cutting plan and say: Not enough. With glaciers melting faster than predicted, and developing nations like China and India bent on growing just like wasteful Westerners, a tipping point is approaching quickly.

Some observers -- including Hansen -- say we might already have passed it. We've dallied too long, they fear, and now, cuts of 80 percent in 40 years won't cut it.

So this is not a request that you trade in your light bulbs, buy locally grown vegetables, insulate your attic or bike to work. Such voluntary reduction of your carbon-footprint is the right thing to do -- but with a crisis of this magnitude, it will never be enough. And so far, our leaders have done, effectively, nothing.

Instead, consider this a call to action -- a symbolic bonfire lit beneath our elected officials, most importantly those in Washington. Because they won't take radical action unless we make them feel the heat.

Hot Time

What's at stake? Here's a clue: Famed economist and environmental thinker Lester Brown subtitled his 2008 book, Plan B. 3.0, "Mobilizing to Save Civilization."

Brown addresses many problems, from population growth to depleted ocean fisheries. But climate change is the big one.

In short, we're headed for what British researcher Kevin Watkins calls a "collision between the energy systems that drive our economies, and the Earth's biosphere."

To avoid that crash, says Brown, we must move to a new, low-carbon economy, "a worldwide mobilization at wartime speed."

Greenhouse-gas emissions are mostly carbon dioxide, and most come from burning fossil fuels like coal and oil. Because live trees sequester carbon dioxide and dead ones release it, about one-sixth of global CO2 emissions result from deforestation (largely from logging, ranching and farming). As these gasses build, they trap sunlight that once reflected back into space.

Eight of the world's 10 hottest years since records were kept (starting in 1880) have occurred since 1998. The rise in average global temperature, though so far just over 1 degree Fahrenheit since 1970, is melting ice sheets, like the huge ones covering Greenland and Antarctica. That is helping raise sea levels: Already oceans are swamping island nations of the South Pacific, and threatening heavily coastal Netherlands.

Possibly more worrisome is the water's temperature. Higher ocean-surface temperatures mean more ferocious tropical storms. But when climate change adds moisture here, it takes away moisture from there: Deserts around the world are growing. And in the Rockies, the Andes, the Himalayas, glaciers on which large populations depend for water and crop irrigation are dwindling.

Such climate changes are just getting started. (Rather than "global warming," we'll say "climate change" because the changes involve more than just higher mercury readings.) Moreover, greenhouse gasses linger for decades. So even if we stopped emitting GHGs tomorrow, planetary temperatures will increase a few more degrees this century, likely resulting in sea-level increases of a foot or more.

And of course we won't be ending our emissions tomorrow. Climate predictions depend largely on whether we cut emissions, or keep emitting at current rates. In his 2007 book Hell and High Water: The Global Warming Solution, for instance, former Clinton administration energy official Joseph Romm calls a stay-the-course scenario "Planet Purgatory." In that case, oceans might rise 20 feet or more by mid-century, and there will be chronic heat waves and crop failures -- not to mention tens of millions of environmental refugees. The biggest victims would be those who contributed least to global warming: the world's poor, especially in low-lying communities that rely on fishing and subsistence agriculture.

Meanwhile, higher temperatures will help disease-carriers like mosquitoes thrive at higher altitudes and higher latitudes -- along with waterborne diseases and invasive species now killed by winter cold.

And the news keeps getting worse.

This past October, the WWF (formerly the World Wildlife Fund), argued that the gold standard for climate outlook -- a rather dire 2007 report by the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change -- was out of date. WWF's Climate Change: Faster, stronger, sooner noted that Arctic sea ice is disappearing three decades ahead of IPCC predictions. The ice might entirely vanish in the next five years, leaving the sea passage ice-free for the first time in a million years, portending bad things for the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, whose break-up rates are a big factor in sea-level rise. Not coincidentally, atmospheric concentrations of CO2 are the highest they've been in nearly a million years: around 385 parts per million, or 100 ppm higher than in pre-industrial times. And they're rising by 2 ppm a year.

Climate change isn't a ticking time bomb. It's multiple time bombs, and some are already going off.

Sweet Home Pennsylvania

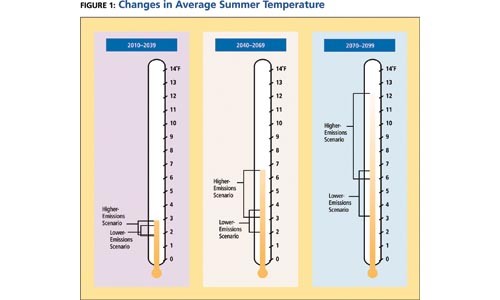

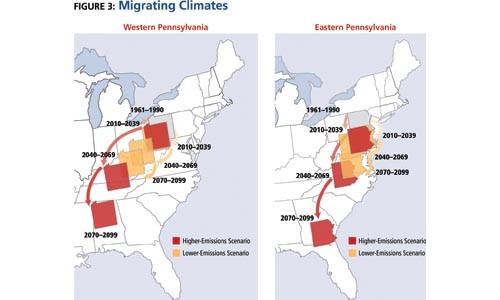

According to a new report by the Union of Concerned Scientists, Pennsylvania's climate is changing too. Temperatures and average rainfall keep rising. That means a longer growing season, but it also threatens the cooler-weather crops we grow now. Already there's evidence of shrinking production in the state's dairy industry.

Meanwhile, says the UCS, Pennsylvania's cities can expect more dangerously hot days, higher levels of lung-damaging ground-level ozone and -- because stuff like ragweed loves both high temperatures and carbon dioxide -- more airborne pollen.

The damage could go well beyond threats to the state's hardwood industry, populations of brook trout, winter snows and maple syrup. Under the UCS worst-case scenario -- which assumes business-as-usual emissions for decades to come -- we'll end up with a climate like northern Alabama's today.

By century's end, days over 90 degrees in Western Pennsylvania could double to 70 a year, with the attendant health risks, plus big increases in short-term summer droughts and spring and fall floods, further stressing our ancient sewer systems. (Arguably, we'd still be getting off easy: Because we get almost all our electricity from coal, Pennsylvania emits more carbon than every state but California and Texas -- more, in fact, than 105 whole countries combined.)

The UCS "low-emission scenario" is 550 ppm -- half the concentration of the worst-case outlook. But is a number that low still attainable? Some observers, like Romm, say we can stabilize concentrations at 550 ppm only with a "monumental" effort to wean ourselves off fossil fuels and reduce deforestation. But other experts say that's too high. The IPCC, for instance, says avoiding the worst of climate change requires stabilizing at 450 ppm, a target widely embraced by environmental groups and green-talking politicians.

And last year, NASA's Hansen co-authored a report ("Target atmospheric CO2: Where should humanity aim?") that said: "If humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed," CO2 levels would have to be 350 ppm -- at most.

"The oft-stated goal to keep global warming less than two degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit)," Hansen told Congress in June, "is a recipe for global disaster, not salvation."

Warm Globe, Cold Feet

The time left to act to avert the worst is often called a "window." In 1988, when Hansen first addressed Congress, the window might have been big enough to crawl through. Instead, we corked it with an air-conditioner. Ten years ago, with the window closing, Clinton/Gore talked a green game but mostly enjoyed the dot-com breeze. Bush drew the blinds.

We can still wedge our fingers in, say people like Hansen. But when he says we have "10 years" to act, he doesn't mean we can wait nine. He means we must enact strict limits and launch efficiency programs immediately. And because the rest of the world (especially China) is waiting for the U.S. to move, we must implement a plan this year.

Why haven't we yet?

Some observers blame our non-response on two decades of cheap oil ... and on Ronald Reagan, who defunded research into wind and solar power. Activists like Romm note how corporate disinformation campaigns sowed doubt about man-made climate change long after most scientists were convinced. They also blame a complicit media and the Bush administration, which censored scientific reports on climate change.

Romm, moreover, cites what he calls "The U.S.-China Suicide Pact on Climate": "America's [nonexistent] climate policy gives political cover to those in China who wish to continue their recent explosive growth in carbon emissions" -- the same growth that keeps the U.S. flush with cheap consumer goods.

Scientists are a temperamentally conservative bunch. But Elizabeth Kolbert, author of the 2006 book Field Notes from a Catastrophe, says climate change is one of those rare areas where scientists are more worried than the public ... the same public that is so quick to panic over things like overstuffed landfills and cholesterol.

"We have really, really good science on this at this point, and we might as well not have had it at all," Kolbert told CP in an interview last February. "We have not changed at all in a practical sense. If there is a culture like ours to look back on ours, we will be like, you know, Rome before the fall."

Indeed, little has changed despite alarms from big names like Thomas Friedman, New York Times pundit and author of Hot, Flat and Crowded: Why We Need a Green Revolution -- And How It Can Renew America. Speaking in Pittsburgh last September, Friedman mocked small-time approaches and feel-good "green" advertising: "We're not having a revolution. We're having a party."

December's U.N. climate talks in Poznan, Poland, weren't much of a party. But neither could attendees from 187 countries accomplish much at this gathering, intended to craft a successor to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol on greenhouse gasses (the one Clinton signed and Bush repudiated).

Poznan was meant only to set the stage for final talks next December, in Copenhagen. Yet even with the bar set low, many think it fell short. A few good things did happen, including a pledge from Brazil, home to huge tracts of rainforest, to cut deforestation by 70 percent within a decade. But overall, wrote British environmentalist George Monbiot, at Poznan government officials were treating climate change as "a minor nuisance that can be addressed in due course."

One problem was that the talks could have been subtitled "Waiting for Barack." Obama disappointed hopes that he'd attend. With Bush still in office, a U.S. delegation had little pull.

"The U.S. holds the key to a successful global climate treaty," the World Resources Institute's climate director, Jonathan Pershing, told London's The Guardian. "Without aggressive domestic action by the world's second-largest greenhouse-gas emitter, other nations will not respond in kind."

Yet a treaty might not happen even with our help. Obstacles include crafting fair emissions-reduction timetables for both poor and rich countries. Another dilemma involves emissions targets themselves: If some negotiators think a CO2 concentration of 450 ppm is unachievable, and others deem 550 ppm unacceptably high, a deal dies.

"We won't see a fully elaborated, long-term agreement in Copenhagen in 2009," Yvo deBoer, the U.N.'s own chief climate negotiator, told Der Spiegel during the Poznan gathering. "It won't be feasible."

But that news may not be as bad as it sounds, say analysts like M. Granger Morgan, head of Carnegie Mellon University's Department of Engineering and Public Policy. Morgan, who directs CMU's Climate Decision-Making Center, says the U.S. shouldn't await a treaty anyway. We've got to lead, for our own good and the world's.

One reason is moral: With 5 percent of Earth's people, we consume some 25 percent of its resources. And with a couple centuries' headstart belching greenhouse gasses, we've had a free ride on cheap gas and coal. It'll be a long time before most of the CO2 in the atmosphere is anyone's but ours.

The second reason is practical: China now emits more carbon than we do (though still much less per capita), and India's fighting to catch up. So the U.S. could stop emitting all carbon tonight, and the world would still be less than a third of the way to an 80 percent cut.

We have to go first. The question is how.

Low-Carbon Diets

The keys to cutting U.S. greenhouse emissions are boosting energy efficiency; minimizing use of fossil fuels; and turning wholesale toward renewable energy sources, like wind, solar and geothermal. We also need to help end deforestation worldwide.

It won't be easy: Coal generates about half the nation's electricity, and then there are all those cars. But if it's all done right, advocates say, we'll break our dependence on dirty fuel sources, and make more energy available to the developing world. We might also save the oceans and keep them from swamping us, while creating jobs and preserving natural habitats.

One common proposal is a moratorium on new coal-fired power plants that don't capture and store their emissions. (Because that technology is untested on a large scale, the moratorium would effectively mean no new coal plants for a while.)

Meanwhile, we'd regulate the amount of carbon that is emitted by making it more expensive -- better reflecting the harm fossil fuels do the planet. Carnegie Mellon economist Lester Lave, for instance, suggests a $40 levy a ton on CO2 emissions, which would effectively double the price of coal. To discourage use of internal-combustion engines, gasoline could be taxed, too, hastening the move to hybrids or plug-in electric cars.

Such plans use at least some tax revenue to offset increased energy costs for the poor. Some plans look to nuclear power, which has no carbon emissions; others reject it as risky, if only because of its millennia-long legacy of radioactive waste.

Perhaps the most ambitious proposal is Brown's Plan B 3.0. World leaders, says Brown's Earth Policy Institute, shouldn't ask "How much of a cut is politically feasible?" but rather "How much of a cut is necessary to avoid the most dangerous effects of climate change?"

To keep atmospheric CO2 under 400 ppm -- closer to what the latest science dictates as safe -- Brown proposes cutting emissions 80 percent not by 2050, the usual target, but by 2020. He says it's possible with existing technology. Brown advocates a carbon tax of $240 a ton, phased in over 12 years. A third of the energy generated in most coal-fired power plants is lost as waste heat; Brown touts a massive efficiency program for factories, offices and homes. He also supports a "crash program" in renewables, with a focus on wind, but also geothermal and rooftop solar. Transportation policy would promote nonmotorized transport, rail and plug-in electric cars. Billions of trees would be planted worldwide to end net deforestation and lock up more carbon.

If this sounds outlandish, consider that from 1976-2005, while per-capita energy consumption in the rest of the country grew by 60 percent, in California it stayed flat. There, state-government programs required utilities to promote energy efficiency -- and let them share in the energy savings. Thanks also to its commitment to renewable energy, writes Joseph Romm, in electricity consumption "the average Californian generates under one-third of the carbon dioxide emissions of the average American while paying the same annual bill."

Who Cares?

We find ourselves needing to reject an assumption as old as steam engines: that energy dug cheaply from the ground and burned means prosperity and progress. Our society is literally built around this assumption, from our oversized buildings to our endless highways.

The task seems impossible, but so far Obama offers hope. He has promised to classify CO2 as a dangerous pollutant, like mercury and ozone (something Bush refused to do). His nominee for energy secretary is Stephen Chu, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist. Obama's science adviser is John Holdren, among the world's top climate and energy experts.

Yet before Obama even takes office, environmental groups fear his "green-jobs" stimulus will be freighted with projects, like new highways, that actually promote fossil-fuel use. (Pittsburgh-area politicians, for instance, are said to seek billions to complete the Mon-Fayette Expressway.) Nations like Italy and Poland, meanwhile, have barely begun to cut greenhouse emissions -- but already say the global economic slowdown precludes further efforts to do so.

Rajendra Pachauri, chairman of the U.N.'s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, said at Poznan that the financial cost of stabilizing emissions (he estimates 3 percent of global GDP in 2030) might be offset by the eventual economic benefits. But it's still a huge upfront tab, with powerful oil and coal companies fighting change every inch of the way.

Even fervent Obama supporters lose sight of the urgency of addressing climate change. In December, when liberal online organizing group MoveOn.org polled members about priorities, just half ranked "green economy and climate change" in the top three -- well behind universal health care (65 percent) and "economic recovery and job creation" (62 percent).

We've been taught for so long that what sustains us is "the economy." But there's no better investment in health care than avoiding global environmental catastrophe. And "economic recovery" won't mean much if the planet on which "the economy" itself depends goes haywire.

Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal didn't happen until labor unions and other popular movements forced his hand. The U.S. didn't enter World War II before Pearl Harbor. And Obama and other elected leaders won't undertake Brown's "world-wide mobilization at wartime speed" on their own.

In December, in the midst of the Poznan talks, Great Britain's environment secretary, Ed Miliband, did something striking for a politician. He called for an uprising.

"There will be some people saying 'we can't go ahead with an agreement on climate change, it's not the biggest priority,'" Milliband told The Guardian. "And, therefore, what you need is countervailing forces. Some of those countervailing forces come from popular mobilization."

So mobilize. Sure, shrink your own carbon footprint -- but also get family and friends urgent about fighting climate change on the public stage. Write letters to elected representatives at the state, local and federal levels, urging strong, immediate action to get us off fossil fuels and onto clean energy.

Join groups that are doing so already. One is PennFuture, which last year helped convince state legislators to put Pennsylvania on the record about undoing climate change. Besides letter drives, PennFuture, through its Cool Pennsylvania initiative, works to involve church and civic groups. It even brings citizen-lobbyists to Harrisburg to turn up the heat. "It's not something we can sit on the sidelines about," says PennFuture's Jeanne Clark.

Or talk to the Sierra Club, through its Pittsburgh field office or grassroots Allegheny Group. The Club, with its Western Pennsylvania Cool Cities campaign, lobbies at all levels of government for clean energy and a moratorium on coal-fired plants in the state, and backs pro-environment candidates. It too seeks volunteers.

Even if you don't want to occupy a coal-fired power plant, like Greenpeace protesters in Poznan did, consider taking to the streets: Climate change is readily linked to social justice, economic recovery and health care. In 2007, some Vermont college students and writer Bill McKibben, with zero budget, sparked a nationwide chain of some 1,400 rallies and marches to raise awareness about climate change. And awareness, it's clear, still needs raising.

Which will change faster, us or the climate? If it's to be us, the change required is so large-scale it must come from the top down. But it won't happen at all without pressure from the bottom up.

Temp Work

Climate Change Resources

Activism

Friends of the Earth. The internationally active group is among the staunchest advocates for the environment. www.foe.org

Sierra Club. The venerable group, with a Pittsburgh field office and its grassroots Allegheny Group subchapter, lobbies against coal-fired power plants and for clean energy, and backs pro-environmental candidates. 412-802-6161 or www.sierraclub.org

PennFuture. The statewide group works to inform and mobilize the public. 412-258-6680 or www.pennfuture.org

Sustainable Pittsburgh A policy-oriented nonprofit that promotes things like public transit and fights things like sprawl. www.sustainablepittsburgh.org

We Can Solve It. The Internet-based group, part of Al Gore's Alliance for Climate Protection, calls for 100 percent clean energy in 10 years through its Repower America initiative. www.WeCanSolveIt.org

Other Resources

Climateprogress.org. Blog run by climate activist and former Clinton administration energy official Joseph Romm, author of Hell and High Water.

Earth Policy Institute. A think tank that's home to the sustainability ideas of famed environmentalist Lester Brown. www.earth-policy.org

Fight Global Warming Now. The 2007 book (published by Henry Holt and Company) co-written by environmental writer Bill McKibben is a primer on climate-change activism.

Pittsburgh Climate Action Plan. The nonprofit Clean Air -- Cool Cities and Pittsburgh's Green Building Alliance assembled local civic and environmental leaders to create this 2008 report. Available at www.city.pittsburgh.pa.us/district8

Realclimate.org. A respected blog about climate science, run by climate scientists.