Bomani Howze arrived early at the Irene Kaufmann Auditorium on July 11, armed with fliers and a disarming smile. Around him, residents of the Hill District and activists from nearly 100 community groups filed into the Centre Avenue building. The room buzzed with the energy of an election day, and for good reason: Attendees were casting ballots to decide who would lead the fight for a Community Benefits Agreement. The campaign could be the city's largest grassroots fight in 40 years. If successful, backers say, that fight could reinvent the way urban redevelopment happens in Pittsburgh.

A community benefits agreement (CBA) is a legally enforceable contract stipulating what benefits a developer must provide to neighborhood residents in return for public support. And Hill District groups have joined with organized labor and others to form "One Hill" -- a CBA coalition that will demand such an agreement before the Pittsburgh Penguins can start developing their $300 million arena and commercial complex.

But while such a fight may be historic, it is also threatened by history -- the differing political agendas and lingering resentments that have often divided the Hill.

For that reason, while Howze was campaigning for votes to be named to the One Hill board, he admits he was "was reluctant to get involved."

"I balance the shame and the shadow," adds the 33-year-old Howze. "The shadow of obviously my father" -- City Councilor Sala Udin. Trying to decide the Hill's future has always been a fractious process, and having ties to Udin, Howze acknowledges, "might intensify the rivalry" over the issue. But there is also "the shame side," says Howze, who taught elementary school for 10 years and is now vice president for the Mental Health Association of Allegheny County: "It would be shameful of me not to bring my skill sets to the community."

Udin himself was in the auditorium that night, though he hardly exchanged a word with his son as Howze, a strapping figure in a charcoal-gray suit, wove in and out of the auditorium to greet those casting their votes. Among them was his father's old nemesis: Tonya Payne, the former Udin aide who unseated her old boss in a 2005 election.

As soon as Payne walked into the auditorium, Howze stepped forth to grasp her hand and ask for her support. Payne responded with a tight smile but not a word. Her allies and staff members dominated the ballots. Of the 15 candidates running for the four positions that make up the coalition's executive committee (chairman, vice chairman, secretary and treasurer), four or more are in her camp.

And when it came time to tally the vote, tensions flared. There were murmurs of disagreement over who should count the ballots. Alma Fox, a highly regarded civil-rights figure in the Hill, held court and assured that there would be no cheating in the counting. "She won't jerk anybody," declared Justin Laing, who emceed the gathering. That was about the only thing everyone in the audience seemed ready to agree on.

Once the votes were cast, Howze wrested the vice president's seat from Carmen Pace, who works at Payne's city council office, by just one vote, out of the nearly 100 cast. Carl Redwood, a respected long-time convener of the Hill District Consensus Group, an umbrella organization of scores of neighborhood groups, was elected chairman. Payne allies Pearlene Coleman and Twanda Moye took the secretary and treasurer seats respectively.

At first glance, it might seem ominous that the leadership of a group calling itself "One Hill" is divided in two. But Howze and others say the stakes are high enough, and historic enough, not to let such divisions dissuade the group from its work.

"My grandparents didn't have the political and economic leverage we have today," says Howze. "This has been a longtime struggle."

The Community Benefits Agreement is part of a new economic-justice movement that has swept across the country in recent years. The movement grew out of a hard-learned lesson over a half-century of urban redevelopment: Despite promises of jobs and renewal, not all mega-developments make good neighbors. And while such projects are often heavily financed with taxpayer dollars, neither the residents nearby, nor the public at large, reap many of the benefits that do result.

"For a long time, people have been settling for way too little. They think any job is a good job," says Pam Feldt, a former University of Wisconsin professor who heads Good Jobs and Livable Neighborhoods, a Milwaukee-based grassroots group that has waged a successful CBA fight.

For far too long, Feldt and others say, developers have held all the cards in inner-city redevelopment. They muscle lucrative subsidies from municipal officials with the promise of jobs and investment dollars. That money tends to end up in the pockets of developers rather than the surrounding community, which is often economically disadvantaged. Construction jobs pay well but don't last, and are often filled by out-of-town contractors. The jobs that remain are mostly low-wage positions in the service sector. The project's neighbors, meanwhile, bear the costs of displacement and increased traffic that developments often bring.

But as inner-city projects have become more popular with developers, urban communities have become more assertive about demanding something in return. Unlike previous development pledges, a CBA differs in that it demands a much wider range of promises. It may include requirements for affordable housing, hiring minorities and people in the community, job-training programs and other amenities. Moreover, these requirements are spelled out in a legally binding contract, which means developers can be sued for not following through on their promises.

If it seems strange that a hockey team should have to build new homes for others, consider how strange it is that taxpayers should help purchase a new home for the Penguins. Besides, developers have long pledged to spread the wealth around. Most such projects, for example, include promises to hire a certain percentage of woman- and minority-owned contractors during the construction phase. CBA backers say they are merely expanding that precedent.

"[The challenge is] to think big, to think that you can ask for and win really good family-supporting jobs, to raise people's expectations, to get people to hang together very strongly," Feldt adds.

The CBA concept was hatched in Los Angeles, back in 1998. Members of the Los Angeles Alliance for New Economy (LAANE), then a fledgling grassroots group, worked with city council to incorporate community-benefits provisions into an entertainment/retail project in Hollywood.

LAANE helped win the city's first full-fledged CBA in 2001. When the owner of Staples Center proposed expanding the facility into a sports-and-entertainment district, residents and small-business owners in the adjacent Figueroa corridor were anxious. Only two years before, the center itself had been rammed down the community's throat, and many residents were displaced by its construction. This time, though, would be different.

Figueroa residents had already fought -- and won -- a union contract for the food-service workers in the nearby University of Southern California. Besides labor organizers and LAANE, the community joined forces with housing advocates and a well-connected welfare-advocacy group in the city to bring Staples Center's owner to the negotiation table. The Staples CBA resulted in 2,500 living-wage jobs, a job-training program for locals, guaranteed construction of affordable-housing, parks and recreation facilities -- even preferential parking for low-income neighbors.

Since then, at least a dozen other L.A. projects have included community-benefits provisions in their development agreements. Other cities soon copied the L.A. model: Groups in Milwaukee, New Haven, Conn., New York and San Diego have recently won CBAs.

Pittsburgh, meanwhile, has had its own disappointing history with urban renewal -- nowhere more so than in the Hill. The densely populated Lower Hill was flattened to build the Civic Arena, which eventually became home of the Penguins. The arena project was the most controversial and racially charged redevelopment of the city's postwar renaissance; although it did clear some dangerous slums, it also eviscerated a thriving, if raucous, business district, which included famed jazz clubs and other black cultural institutions. To protest these wrenching changes, Hill District residents mounted a billboard that declared: "No development beyond this point." That point, near St. Benedict the Moor Church, is today marked by the monument known as Freedom Corner.

The arena was to be followed by developments that would have benefited the working class, such as affordable housing. That, in the form of the mixed-income complex Crawford Square, didn't come until 30 years later.

This time around, the Hill District isn't willing to wait that long. Local activists didn't just borrow a page from L.A.'s playbook; they are building the whole organizational structure from scratch. In preparing their CBA fight, they have coalesced into an organized group and reached out to national organizations. In fact, this June a community organizer from LAANE visited the Hill District to lend support; other national organizers have followed.

The One Hill Coalition has yet to formally decide on the specific planks its bargaining team will bring to the negotiation table: Members are slated to vote on their demands on July 28. But the demands being discussed range from a neighborhood grocery store -- which residents have been seeking for years -- to job-training programs, money for economic development and social services.

And those demands are only the beginning. Organizers hope that the One Hill campaign will be a model for CBAs elsewhere.

The arena, after all, is only the first of a string of major developments being planned in town. There are also the casino planned for the North Shore, the expansion of Duquesne University in Uptown, and ongoing redevelopments in East Liberty.

In January, a coalition of local and regional groups, including Service Employees International Union Local 3, the League of Young Voters, the Mon Valley Unemployed Committee and the Housing Alliance of Pennsylvania, applied for a grant to set up a permanent organization that would help launch all future CBA negotiations and other economic-justice campaigns.

The three-year, $500,000 grant, funded by local foundations with a match from Ford Foundation, gave birth to Pittsburgh UNITED. The new organization is also meant to be a local chapter of the Partnership of Working Families, a national grassroots group aiding local fights for economic justice.

Heading Pittsburgh UNITED is Tom Hoffman, a longtime Local 3 organizer.

With his black-framed, elongated glasses, Hoffman looks more like a college professor than the battle-hardened union organizer that he is. For many years he has donned the bright purple SEIU T-shirt, waging the Justice for Janitors campaigns across the city.

Pittsburgh UNITED is not just an ad hoc project, Hoffman says, but rather a policy action center -- one that will "have a permanent capacity to do research, policy work and organizing."

For Hoffman, the CBA negotiation is a natural evolution for the labor movement.

"Good jobs are what the labor movement is about," he says. But while the promise of jobs comes with every large-scale project, a CBA "can be broader to include affordable housing and environment enhancement. It has the chance to build a broader coalition and have a larger impact on people's lives."

Not surprisingly, in mobilizing for the CBA negotiation, Hoffman plans to employ tried-and-true labor tactics.

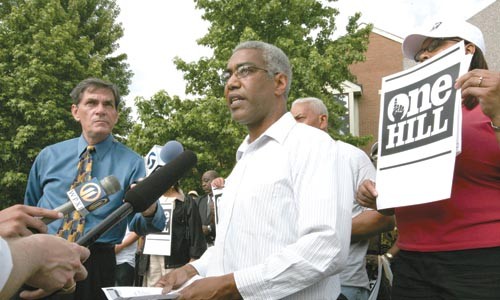

During the July 11 meeting, while votes were being counted, Hoffman schooled his audience in how the CBA campaign will be mobilized. Using a black marker, Hoffman charted the organizational structure on a flip board, using the lingo of a union contract campaign. He explained that a negotiating team would represent the One Hill coalition in hammering out the CBA with the city, the county and the Penguins. A street team, made up of engaged Hill residents, would be dispatched to communicate the latest developments to the neighborhood residents, bring back community feedback, and turn out large crowds, if need be. Anything negotiated would be brought back to the coalition's entire membership to be voted on.

"Here is your chance to create the perfect campaign," says Hoffman, as he concluded the talk.

In practice, however, the CBA fight is shaping up to look very different from a union campaign. In a labor fight, time is often on the workers' side. But here, there can be no job actions or stalling tactics -- because time is running out.

In June, the Penguins won their demand for development rights to the 28 acres of the current arena site. With the state budget passed on July 17, the Penguins secured the $225 million in funding from gambling proceeds needed to build the arena. So far, the Penguins have gotten whatever they've wanted from politicians -- without having to promise anything to the Hill District. For example, during the budget process, state Rep. Jake Wheatley, who represents the Hill, sought to allocate $15 million in slots money to a neighborhood-development fund. That measure was stripped from the version of the budget that finally passed.

As far as the coalition sees it, the Penguins hold nearly all the cards: The only leverage point lies in the government's approval process for the arena's master plan. The plan will spell out the design of the new arena and how it relates to the existing infrastructure in its surroundings. The city Planning Commission will have to approve the plan and then submit it to city council for a full vote.

The master-plan review is the final serious government hurdle the Penguins have to clear, and officials hope to have the plan approved by September, so the arena can be completed in time for the 2009 hockey season. Generally, master plans focus on traffic flow, aesthetics and infrastructure at the development site. But One Hill is seeking a plan that takes a more holistic approach.

"The CBA must be linked to the master-planning process," One Hill chairman Redwood insists. "The public-approval process should be based on public benefits. What is the benefit for the people in this whole deal? [The planning approval] shouldn't be just about what kind of glass and steel they use."

Milwaukee has been down that route before. In 2003, a coalition of activists mobilized to incorporate public-benefit provisions into a master redevelopment plan for a huge tract of land newly cleared from the demolition of a highway overpass. Called "Park East" after its location immediately east of downtown, the tract was controlled by a patchwork of owners, including the city redevelopment authority, the county and private developers. Initially, organizers failed to have their concerns addressed in the master plan; the mayor and city councilors were interested in the physical specifications of the redevelopment, but neglected the human dimension of community concerns.

"The redevelopment authority didn't want to take up controversial issues," says Feldt, of Milwaukee's Good Jobs and Livable Neighborhoods. "I'd call it a coward way out."

After the defeat on the city level, however, the coalition's cause was taken up by the county board of supervisors. The county was the largest owner of the tract, and its board overwhelmingly passed what would become the first legislative CBA in the country.

In Pittsburgh, officials are saying: "Trust us." In mid-June, Mayor Luke Ravenstahl, Allegheny County Chief Executive Dan Onorato and Penguins CEO David Morehouse signed a letter confirming their commitment "to work in good faith toward a community benefits agreement." However, they also say in the letter that they expect that the city planning approval of the new arena plan "will not be delayed or disadvantaged by our good-faith negotiations regarding any potential community benefits agreement."

In other words: We promise you'll get your way ... so long as you stay out of ours.

The Penguins have declined CP's several requests to discuss their stand on the CBA. But public officials maintain that at the end of the day there will be a CBA -- because they, too, believe in it.

"From the county standpoint, I think [a CBA] is very important," says Dennis Davin, chief of the county's economic-development department. "The Penguins want to be good partners and good neighbors. This is a chance for us to rally around to look at the opportunities in the Hill District."

However, it's going to take far more than a pledge of good intentions to satisfy the Hill, where the current arena blisters with the memory of broken promises in the past.

"We don't trust them. Just because people say that they're going to make an agreement, it doesn't mean it is going to be in our interest," says Redwood. "Our faith is in the people in the community who live and work in the shadow of the arena -- in the shadow for the past 40 some years. The people are our leverage."

But for that to work, advocates agree, the people must be united. Which means the real test has begun: Can the Hill District, where leadership has often been divided, put aside political rivalries and stick together to fight for the city's first ever CBA?

Barely a year ago, the neighborhood was divided by another skirmish involving the Penguins, who were then seeking to build not just a new arena but a casino next door. In partnership with casino developer Isle of Capri, the team pitched a mixed-use redevelopment to remake much of the area surrounding the arena. Isle of Capri formed a front group called Pittsburgh First, which sought to drum up community support for the casino. Payne was among the Penguins' most vocal supporters; when a group of casino skeptics began agitating for neighborhood investments should the casino be built, she accused them of "extortion."

"You can't ask [casinos] for their money, and then say, 'If you don't give me the money, we won't support you,'" she was quoted saying in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Now Payne's loyalists are leading One Hill, whose purpose -- extracting investments in the Hill's social and physical infrastructure -- seems much like the efforts she previously decried.

Payne did not respond to numerous requests to interview her for this article. Pearlean Coleman, the Payne ally elected to be One Hill's secretary, referred all questions to Redwood.

Such divisiveness is the norm "for a lot of low-income communities," says Greg Crowley, research director for the Coro Center for Civic Leadership. (Coro's president is Sala Udin, the former Hill District councilman.) Crowley's 2005 book, The Politics of Place, studied grassroots efforts to contest urban-renewal projects, and he says low-income communities face special obstacles. "By definition these communities have historically suffered from changes in the world around them. ... [W]hen you have that history of being overlooked and your community still struggles, the resentment against the people in power makes it very hard to unify around a positive agenda."

The result, Crowley says, is an "imbalance of power," in which the private sector is able to "speak with a strong voice with the government" while neighborhoods "are larger in number and more diversified, more suspicious and angry and [it's] harder to establish a voice."

But Redwood says he's ready to bridge the divide within the Hill, because everyone involved in One Hill shares the same mission: "to work together through our differences and find our commonalities."

They'll have to do so quickly: Having chosen its representatives in the July 11 election, One Hill is now charging forward to assemble its demands. It hopes to have its platform hammered out by Aug. 1 -- just six days before the Penguins present their plan before the city planning commission.

"We had to get all our partners on board; it was a broad process. It's not a closed room with a few people; [otherwise,] we won't have the support that we need," says Redwood. "Our issue is to make sure the folks Downtown understand that we speak with one voice."

"You have to have a united front," agrees the Rev. William Smart, the LAANE organizer who visited the coalition last month. "I think right now they're going through the process," says Smart. "You have to have one voice."

But as desirable as it may be for the Hill to speak with one voice, some say it isn't entirely realistic. In fact, demanding that the entire Hill think the same way may be an excuse for ignoring its wishes completely.

"There are various interests in the Hill," says state Rep. Wheatley. "To say that we all have to speak with one voice is problematic." When officials say, "We need you all to be saying the same thing in order for us to deal with you," he adds, what they really mean might be "We don't want to deal with you."

But in the end, says Smart. "No city officials or developers are going to oppose a large, diverse coalition.

"I always believe as long as the community is united, they'll be able to get what they want."

Crowley says that the Hill District has already taken an important step forward ... but that the work has really just begun. A CBA "institutionalizes the voice of the community in the process of making economic-development decisions. That's a good thing. If Pittsburgh UNITED can gain credibility to ensure communities benefit from investments, [investors] are more likely to respect that voice, rather than make their decisions independent of the community.

"The key is whether they can organize around a single theme, a single message. That depends on the quality of leadership. ... They need to move quickly because time is of the essence."