"This is amazing to me," says Anne Messner. On a January day, she's laid her hand on a wide, tiled window sill on the first floor of McKeesport Downtown Housing, the low-income facility where she is property manager. "Feel it. It is 7 degrees out or something," she says — yet the tile feels indistinguishable from the indoor air, the thermostat reading 73 degrees.

That is pretty amazing, especially considering that the four-story brick building — a former YMCA — is nearly 100 years old. But it's no accident. A year ago, the MDH's structure completed an ambitious renovation meant to make it a "passive" building, one with both a measurably high comfort level and very low energy use. Experts says passive-building principles can help shrink our carbon emissions and fight climate change.

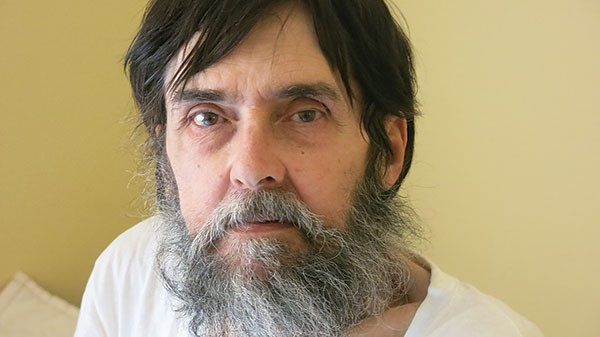

Technically, the MDH building didn't quite achieve the rigorous, quantifiable passive-house standard. But the improvements are vast. When it was the YMCA, housing 84 residents, the building had its original radiator heat and no air-conditioning. That meant it was "too hot" in the winter and "miserable" in the summer, says Paul Pirch, a former resident who's now a maintenance worker there.

In 2012, the building was acquired by an ownership group including the nonprofit ACTION-Housing, which spearheaded the 18-month, $10 million renovation (financed with low-income tax credits). The remade MDH still houses 84, a homeless shelter and other homeless services. But now the rooms are bigger (if still modest); it's got air-conditioning and more consistent heating; and an elevator has replaced the big central staircase. And every resident got his or her own mini-fridge and microwave. "Everything is better, everything is bigger," says Sonny Kozak, a resident for about a decade.

You'd think all those improvements would have driven utility bills through the roof (itself now made white to reflect solar heat). But they didn't. The Y's utility bills were about $60,000 a year, says ACTION-Housing director of housing and neighborhood development Linda Metropulos. MDH's utilities for the first post-renovation year cost $42,000 — about 30 percent less.

There were two main reasons for that savings. One was passive-house strategies to greatly lower the building's energy needs. Most buildings leak heating and cooling "like water," says Laura Nettleton, a principal of Pittsburgh-based Thoughtful Balance, the project architect. "All of our mechanical systems are trying to heat up the outside, and we can't do it."

The passive-house idea is to heat the building as much as possible with sunlight and the warmth of the people and machines inside. (In summer, it's about keeping cool air in and warm air out.) But to get the desired energy savings of 75 percent or more requires airtightness and insulation. For MDH, that was achieved not only with new high-performance windows but also with 8 inches of spray-foam insulation applied to the inside of every exterior wall (thus the wide window sills).

The other technique was geothermal energy: On MDH's grounds were dug a couple dozen deep holes where loops of refrigerant-filled piping harvest the earth's constant temperature to heat or cool air that's then pumped through the building. (MDH's system is electrical, no gas hook-up required.) There are also devices to keep the air comfortably dry and filter contaminants.

The passive-house idea dates back decades and is most popular in Europe. But it's gaining in the U.S. Three years ago, the Passive House Institute of the U.S. had certified only a dozen buildings; now there are about 130, with a comparable number in the pipeline. Pittsburgh has a couple of passive houses, including one ACTION-Housing built in Heidelberg in 2012.

Despite their savings on mechanical systems, passive houses are a bit more expensive to build, by as much as 10 percent. (However, the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency recently began awarding extra points to applicants for low-income financing who pursue passive-building standards.)

But in environmental terms, passive strategies' biggest impact is probably in retrofits like the McKeesport Y. After all, most of our buildings are going to be old for years to come. Says Nettleton, of Thoughtful Balance, "We are not going to get out of the carbon crisis by building new."