Although he was in the minority camp that opposed City Council’s June 7 approval of the landmark designation, Burgess’ statements resonated with many of the people supporting the effort to preserve the Victorian house and former beer distributorship where much Pittsburgh history was made.

Those pushing for landmarking the site ultimately won their case. Yet, they believe the path leading to the win was fraught and impeded by inept city planners and a conflicted and culturally and historically incompetent Historic Review Commission. Burgess, who recognized the building’s historical value, said his opposition was based on a personal policy of denying landmarks to properties in cases — like this one — where the owners object.

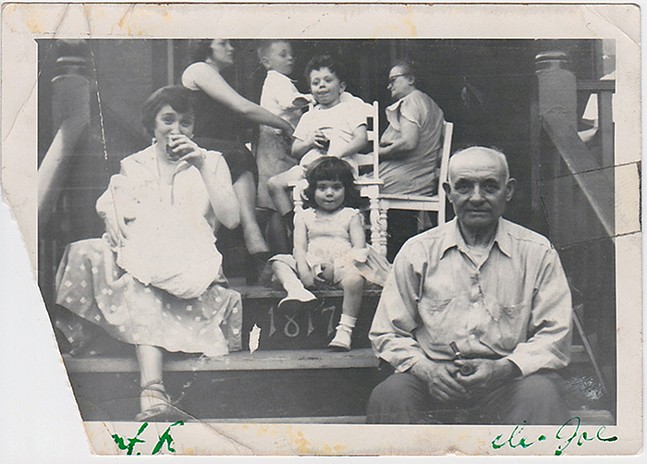

The Uptown parcels were once owned by Joe Tito, a son of Italian immigrants who developed a reputation as one of the city’s most colorful bootleggers and gambling racketeers. Today, the two properties are owned by the heirs of families who have owned them for more than 50 years. And they vehemently opposed the historic preservation effort.

Joe Tito played key roles in the emergence of a nationally organized crime syndicate in the 1930s (La Cosa Nostra) and made history as a co-owner and vice-president of the Negro Leagues baseball team, the Pittsburgh Crawfords. After prohibition, he and his four brothers bought the Latrobe Brewing Company, where they conceived their signature product, Rolling Rock beer, in 1935.

Peckich, who lives in California, enjoyed the photos from that tour on Facebook. She loves her family’s history and she was a key collaborator in the nomination project. To say that historic preservation here let her down would be an understatement.

“I was very disheartened with that and it was obvious from day one with the HRC that there was a problem with how they felt about my family specifically,” Peckich told me after the February HRC vote to deny designation. “And we just never got past that.”

Despite the obvious historical value and the support of the Tito family, if the HRC had its way, the building would be erased without remorse.

Historic preservation in Pittsburgh is a three-part process. Two advisory boards, the Historic Review Commission and Planning Commission, hold hearings on proposed landmarks. The City Council then has the final say, taking into account recommendations from the two boards.

The HRC evaluates nominations against 10 criteria for designation, and the planning commission considers whether landmarking a property is consistent with neighborhood and city planning goals. City Council weighs all of the factors, including political ramifications, and makes the final call. Typically, if property owners object to the designation, Council declines to approve, even with enthusiastic HRC and planning commission recommendations.

The February HRC hearing was the second of two sessions where the board discussed the Tito-Mecca-Zizza House. Both featured long rants by commissioners about the property’s ties to organized crime and what they perceived to be a lack of historical significance. Their comments bore no resemblance to the many letters supporting the nomination written by internationally renowned scholars in Black history, Italian-American history and culture, historic preservation, sports history, and Pittsburgh history.

As the gatekeepers for Pittsburgh’s heritage, the HRC displayed an alarming level of cultural and historical illiteracy. Its staff person, Sarah Quinn, repeatedly erased Black and women’s history in her briefings and reports. It was so apparent when the case made its way to the planning commission that chairperson Christine Mondor had to remind Quinn about the property’s links to Black history in a February briefing prior to the body’s unanimous vote to designate the landmark.

“Sarah, thank you for opening us up to the history of this property. It’s really interesting and I see there’s even other history that goes back to some of the first Black-owned baseball fields,” Mondor said.

Quinn’s presentations before the HRC and Planning Commission focused instead on the property’s more salacious attributes and its architecture. In fact, in the November 2021 meeting, mention of Black history was missing altogether from her presentation to the HRC.

I repeatedly asked for clarifications from planning department managers and I received no replies. I subsequently wrote about the erasures in a March Urban History Association blog post.

HRC commissioners Matthew Falcone and Richard Snipe voted to deny the nomination, citing the property’s connections to organized crime. They ignored the testimony and documentation about Tito’s close friend and Negro Leagues, bootlegging, and gambling partner Gus Greenlee’s Crawford Grill No. 2 being listed in the National Register of Historic Places. And, Woogie Harris’ home, now known as the National Negro Opera Company House, is a city landmark.

In all landmarking cases, the buck stops with the City Council. Council members R. Daniel Lavelle (D-Hill District) and Bruce Kraus (D-South Side) both indicated that they would have voted to deny the designation had it not been for the overwhelming support for landmarking voiced by their constituents. Both members stated they believe that property owners should have the final say in whether or not their properties become city landmarks. Their votes tipped the scales to the supermajority of six votes necessary for approval.

Historic preservation is so broken — tainted — in Pittsburgh that it was the subject of a 2011 University of Maryland PhD dissertation by former resident Ruth Bergman. Her 365-page study also exposed the erasure of Black history by the HRC and other shortcomings in how the law is implemented.

After the council bucked its own precedents and voted to landmark her family’s former home, Peckich agreed with Burgess’ comments about historic preservation here. “His little critique there is basically how I feel now that I’ve been through the process of this designation process in Pittsburgh,” Peckich said in a telephone interview five days after the council vote.

In the Tito-Mecca-Zizza house case, it doesn’t take a dissertation or a doctorate to recognize a bad and immoral process. All it takes are working ears and eyes. Pittsburgh has a new historic landmark, but at what cost?

Editor’s note: David Rotenstein worked as a paid consultant to Uptown Partners on the Tito-Mecca-Zizza House designation. Much of his academic work focuses on racism and other biases in local historic preservation programs.