Tuesday, December 12, 2017

An interview with Eric Kimmel, author of Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins

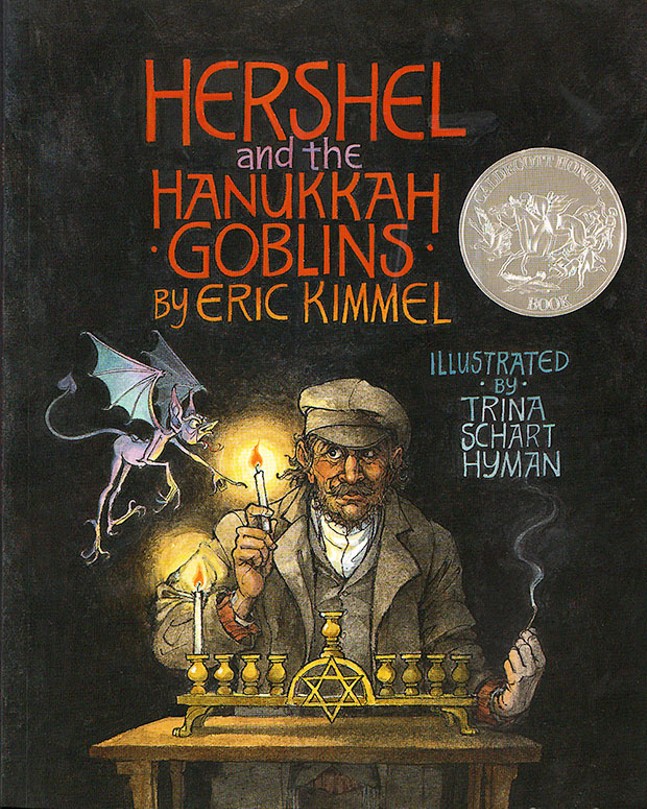

The illustrated storybook tells the tale of Hershel of Ostropol and his efforts to reclaim a small town synagogue from a gang of mischievous goblins who are hellbent on stopping Hanukkah. The book, written by Eric Kimmel with illustrations by Trina Schart Hyman, was first published in 1989 and has endured as a quintessential Hanukkah book — though, as Kimmel told CP, its reach extends far beyond the holiday or even Judaism in general. It was named a Caldecott Honor Book in 1990.

Hershel is a dark story, both visually and conceptually. With the lighting of Hanukkah candles forbidden by the goblins, the snowy town is draped in eerie, dull shadows. Re-reading it as an adult gives me the same spooked feeling it gave me as a kid, which is true of everybody I talked to for this story. There's plenty of humor and good-natured mischief, but I think what makes Hershel endure is its lack of sugar-coating. There's real danger and real fear at play.

For a little background: Kimmel writes in the afterward that he wanted to "see if [he] could create a Hanukkah story along the lines of Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol." He chose Hershel of Ostropol, an old school Yiddish folk character, as his protagonist. Hershel is a vagabond, a traveler who goes from town to town getting into trouble and using clever, playful tricks to get out of it. He's a jokester.

One favorite Hershelism I've latched onto is the story of Hershel having a Passover seder and sitting across the table from a pompous rich dude. Hershel, as an itinerant pleb, eats with his hands and makes a mess. The rich guy, disgusted, asks what separates Hershel from a lowly pig. Hershel replies, "the table." He's a hoot.

Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins has been a pretty big part of my life for 30 years (that's all of them). My mother has bought it for what seems like dozens of relatives. We spread it like gospel. A few weeks ago, I figured it couldn't hurt to reach out to Kimmel and ask him about how this phenomenon came to be and he was more than happy to talk. To be clear, he's not from Pittsburgh or anything; there's no local connection, I just really wanted to talk to him and our conversation turned out some gems.

A few housekeeping points: There will be spoilers here. We discussed the book in its entirety. It won't ruin anything because the joy of the book is in the physical reading of the words and looking at the amazing illustrations. And just for a little overview: Hershel arrives in a town on the first night of Hanukkah; the townspeople are not celebrating because goblins have taken over the synagogue and they hate Hanukkah and forbid it. Hershel offers to confront them; he's given a few items and heads to the synagogue. He encounters a different goblin each night and has to outwit them in order to light the Menorah. See? It works much better as a book.

Happy Hanukkah! Here's CP's talk with Eric Kimmel, lightly edited for clarity.

__

What type of stories did you like as a child?

I’m a kid of the '50s. And I had an interesting upbringing because I loved the folk and fairy tales; an uncle of mine gave me a copy of Grimms’ Fairy Tales and I read it over and over again until the book fell to pieces. My grandma lived with us, she was an old-country grandma; she came to the States when she was in her 30s and never really liked the U.S. She was always homesick for her old hometown in Eastern Europe. She was a good storyteller, so she told lots of traditional tales from Europe, and most of them were scary, full of devils and demons and spirits and things like that. The moral was usually “listen to Grandma or bad things will happen to you.”

That was in the era of the great classic horror movie. The Creature From the Black Lagoon and Godzilla. I just loved those, they scared the pants outta me! But I came back for more and more and more. I’d look at at the ads in the paper, and my hair would stand up on edge. So I love creepy stuff, I love to be scared. And I must say, the scary things back then were nothing like what they are today. You never saw any blood, there was never gore, chainsaws, organs, limbs scattered all over the place. It was all in your imagination, which made it all the more terrifying. So I always liked creepy stuff, and I thought that creepy stuff made for an interesting story.

Years I spent as a storyteller in the parks when I was working as a graduate student at Illinois, you know, I learned [that] you gotta keep the kids interested. And what the kids want is “tell me a story,” so tell them a story, make it good. Kids, once they get to a certain age, absolutely love scary stories, dark, creepy tales. So that’s the kind of book I always loved and the kind of book I liked to write. What I say to every beginning writer is “write what you love, write the kind of story you’d want to read as a kid.” I’m still doing that.

I read that the original version of Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins was a bit longer.

Oh yes! There was a goblin for every night. It made for a very long story. I was shopping it around, and no editor really got excited about it, but my friend Marianne Carus at Cricket magazine called me up. She needed a Hanukkah story for their December ’85 issue … and I didn’t have anything! I just had this funny old tale that nobody wanted. So I sent it to her and she said, “Oh, it’s great, I want this, but it’s way too long.” I think the limit for fiction at Cricket was 1,800 words and this was way over, maybe 2,500 or 3,000 and when you’re writing for magazines — like you know, writing for a newspaper — you gotta cut. So OK, I cut. I cut out the three middle goblins, and so when you get to that part — “and on the next three nights, other goblins came blah blah blah” — that’s where the missing goblins were. I just stitched the first part and the ending of the story together, and I had it under the word limit. I ultimately decided that it was a good idea because writing always gets better if you can cut something. And those goblins weren’t my favorites, anyway.

How did you choose which goblins to cut?

I figured something’s gotta go, so I asked, “Which goblins do I like the best?” I knew I wanted to keep the little guy, the stupid guy with the pickles was my favorite, the big red one, the gambler, I liked him too. Then I had to keep the King of the Goblins. So three is a good number for tales, so I had three, then the King is gonna come for the climax, and that was a good balance. I think when I had a goblin for every night, I was just indulging myself, and the story was better for being cut. It’s like, “OK, let’s get on with it.”

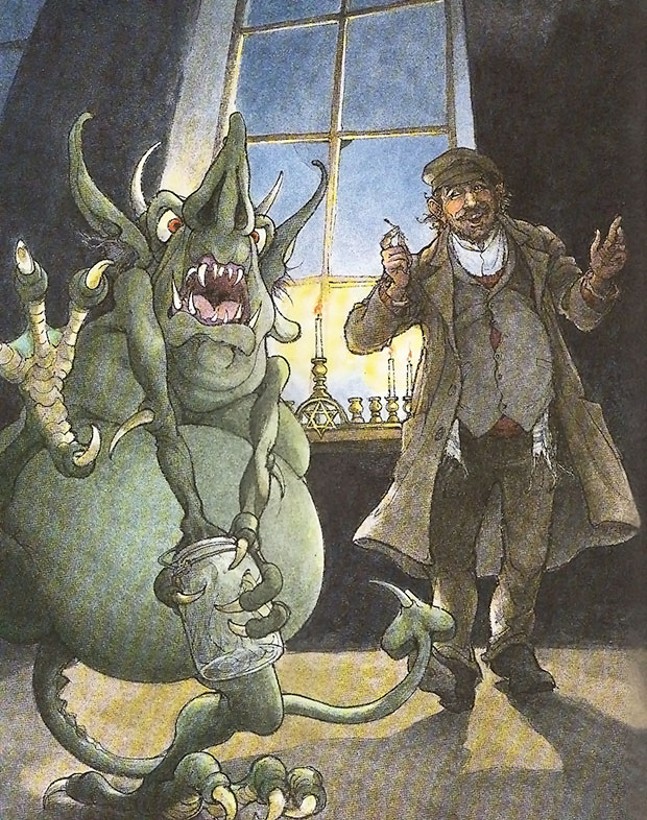

Sometimes morals in kids’ stories can be heavy-handed or too subtle, but the pickle-jar goblin came in so clear to me as a kid, I understood it completely, without feeling condescended to or wondering what it meant. I loved it and understood it so simply — he just had to let go.

Yes, he just had to let go! There’s a funny story about the pickle jar, I still love telling this story to kids, it still cracks me up. When we were kids, if you wanted pickles, you went to the corner grocery-store delicatessen, and you told the man how many pickles you wanted, and he would fish the pickles out with tongs out of a big barrel, where the pickles were in brine, a yellowish-greenish brine. And the only thing covering the pickle barrel was a wooden board on top, a wooden lid. And the pickles were delicious! But a couple years ago, my brother pointed out, “You know, these were old buildings, they were infested with cockroaches and mice. It was only that wooden lid on top of the pickle jar — what else was down there in the bottom of the barrel with the pickles??” [Laughs] I thought, “Ahhh that’s what made them taste so good, they were fermenting down there with rats and mice!” So that’s why the pickle jar always cracks me up, because the pickles coming out of that yellowish brine — oh, how good they tasted — but I didn’t think about what else was down there with them.

Do you have a favorite illustration in the book?

The illustrator Trina Schart Hyman was a very close friend of mine and was one of the great illustrators of the 20th century, just a very dear friend and one of the people I’ve met in my life who I’ve admired most. I have a lot of favorite pictures there, but the one I have that I actually bought from Trina, is the one — I’m gonna go out in the living room and look at it, I have it right over my mantle — well, it’s the one with the pickle jar! The big fat green goblin’s trying to get his hand out of the pickle jar, and Hershel is laughing at him. Saying, “Can I tell you how to free yourself? Let go of the pickles! Your greed is the only spell holding you prisoner.” I loved that picture so much I bought it from Trina. I should have bought some more. But we have that framed over our mantle. That would be my favorite. But I love all of it.

[Hyman] loved that story. She got it. She caught all the humor. It’s interesting, she was so happy to get the opportunity to illustrate. She illustrated it in Cricket Magazine, and then she wanted to do it again as a picture book; she wanted another crack at it in full color. She said that at that time she was the queen of knights in armor and maidens in distress. Trina could be very funny and very profane — you might not want to print this — but she’d say, “Why is it every time somebody writes a fucking story about some prince and a maiden in distress, they send this crap to me?”

So she liked Hershel because she got to draw all these weird characters. As she said, “I think I fell in love with Hershel, because he’s a bit of a rogue, you know, he’s unemployed.” Today we’d call him homeless or a street person who wanders around, and he was such a difference from the knights in armor that she was getting very very tired of. It was nice to take a holiday down to the lower class of the goblins and leave the wicked queens for somebody else for a while.

I think my favorite image in the book is the first time you see the King of the Goblins in the doorway.

Oh yeah!

I remember that really clearly. The first few goblins are kind of fun, but they do get more intense each night, and I just remember the sight of that goblin, it’s titillating, it’s scary.

Oh yeah, well, that’s part of the storytelling craft. You build towards the climax, and the climax is the confrontation between Hershel and the King of the Goblins. And Hershel has nothing — he is not a superhero, he has no special powers, he’s on his own. He says, “Master of the universe, stand by me now!” Because without some supernatural power behind him, he’s gonna be squashed flat. It’s sort of like giving yourself up, “I’ve done all I can, God, now it’s in your hands.” You build to that, because the previous goblins are stupid and Hershel can outwit them. If you keep repeating that pattern, the story becomes dull and predictable, so you have to build to the climax.

The King of the Goblins is no fool. And what is Hershel gonna do when he shows up? That’s why nothing happens on the seventh night. “You’re not supposed to come until tomorrow.” “Don’t worry, Hershel, I can see you and speak to you, I’m on my way, my friend. Tomorrow night I will come for you.”

It’s building that tension … the King of the Goblins is a bully, a sadist. “I’m gonna let you stew in your own fear for a whole day until I finish you off.” And that’s also his undoing! Because “I want to see you sweat, I want to see you suffer, I want to see you crawl on the ground and beg.” He’s a bully! His real satisfaction comes from pushing people around, and the way you deal with bullies is you don’t back down, you don’t show any fear. Hershel laughs at him. “I don’t believe you are who you are, Prove it to me!” And that’s the King’s undoing, that’s his weak spot. Once he lights the candles, he’s finished. So that was my thinking, when I was creating the story.

It’s pretty classic, it fits a pattern that you find in any number of folk tales, and the reason it’s lasted through the centuries is because it works. That’s how you tell a story.

And that’s one problem that you find with so much of what’s offered in films today, and a lot of books. They’re very predictable, they follow a formula, and you don’t feel that tension. It’s like, “OK, how are they gonna solve this problem? But I know that the superheroes are gonna come back for another adventure.” With Hershel, you don’t know that. There’s never been a sequel and there’s never gonna be one.

Why do you think this story has such a lasting impression on people like me all these years later?

Well, it’s going into it’s third generation now, and that’s pretty good for a story that, in the beginning, I couldn’t give away. I think part of it is because I was breaking the mold. It wasn’t my intention, I just wanted to tell a good story. But religious stories, especially Jewish stories, were very sweet and nice and safe and friendly, and this was the first story to come along that wasn’t. There was some real danger here, there were some really scary characters — scary but interesting. And not only Jewish kids could plug into it, but kids from all backgrounds. I’ve had kids come up to me and say, “it’s my favorite Halloween story,” and I say “Yeah, well, if you wanna use it as a Halloween story, that’ll work! What matters to me is that you enjoy it.”

So I think one of the reasons it was successful is because it was aimed at kids and what kids like, and not aimed at grownups to make them feel good. Because children live in a world that’s controlled by grownups, especially these days. When I was a kid, we had a lot of freedom. When we were home from school, we told our parents we’d be home by dinnertime, and we went wandering, had adventures. And nowadays, your parents are taking you to Little League, or your tutor, or here and there, and you live entirely under the thumb of your parents. So I think with Hershel, one of the reasons kids found it so exciting is there are no grownups. Hershel is the character they identify with. He’s the kid, and he’s on his own, and he’s gonna solve his own problem. He’s gonna deal with the all the baddies in the world around him. You don’t know how he’s gonna do it, but you kinda have faith that he’s gonna come through. And if he can come through, then so can you.

Tags: Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins , Eric Kimmel , Trina Schart Hyman , Hershel of Ostropol , Image