Richard Pell's photos, shot in the parking lot of a local Walmart, depict giant pumpkins. The gourds, submitted for a contest this fall, are boulder-sized, so heavy on the vine that they warped into blobs out of Dali.

Some might call them grotesque. Pell views the photos bemusedly. "Those are post-natural wonders of Western Pennsylvania," he says, grinning.

Pell, 37, an assistant art professor at Carnegie Mellon University, founded and runs the Center for PostNatural History. Its unassuming Garfield venue sits amidst the art galleries and other storefronts on Penn Avenue. But this mini-museum dedicated to life-forms intentionally altered by humans is unique. Starting where traditional natural-history museums end, the Center even has a touring component that's visited Amsterdam and is booked for Berlin, Germany.

Post-natural life arose some 10,000 years ago, when humans began breeding domesticated animals and plants out of their wild forebears: Milk cows, housecats and corn were, like 1,000-pound pumpkins, unknown in nature. In recent decades, post-natural organisms have also proliferated through genetic engineering: tomatoes implanted with flounder genes for frost resistance, mosquitoes lab-crafted to curb malaria.

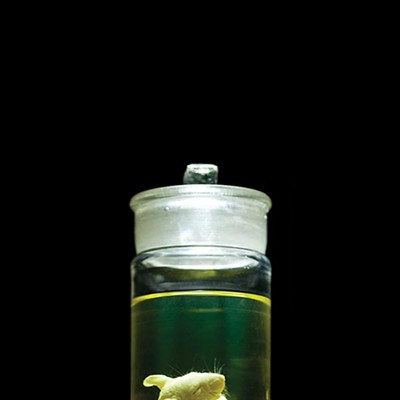

Genetic modification is controversial, with debates over matters considerably more worrisome than hypertrophic gourds, from food safety to the ethics of patenting living organisms. But the Center, which opened in March, doesn't take sides. Its airy foyer displays colorful posters of transgenic fruits and vegetables now being field-tested (like a Monsanto onion with "herbicide tolerance") or already approved for use. Wittily, Pell offers trading cards featuring genetically modified organisms like a blight-resistant chestnut tree. On some shelves sit a Rottweiler skull and a jar containing a warped-looking, immature transgenic pheasant. A book-length collection of government documents, painstakingly photocopied by Pell, is titled U.S. Patents on Living Organisms, 1873-1981. It lists everything from virus cultures to "ruminant feed additives."

Though run mostly by Pell and University of Pittsburgh graduate student Laura Allen, and funded by small foundations, the Center is surprisingly expansive. In its large, dimly lit back room are museum-style vitrines, most with old-school telephone handsets playing informational recordings. One diorama depicts the government base where the Department of Defense raises BioSteel goats — genetically engineered to produce milk containing spider-silk protein for bulletproof armor. An aquarium contains a couple of GloFish, zebrafish supplemented with coral genes by Yorktown Technologies so they glow under UV light. GloFish are sold as pets, but only in the U.S.

Another display contains a flaskful of kernels of Monsanto's widely planted, much-criticized RoundUp Ready corn. It's engineered to resist the popular herbicide, but legally prohibited from replanting by farmers. There's also the H5N flu vaccine; the preserved testicles of a neutered cat; and a bowl of live brine shrimp (a.k.a. the comic-book novelty "Sea Monkeys"). And there's a wall-sized video projection of a vintage film about lab mice confronting a food puzzle. "At last he hits the bar and gets an immediate reward of food," says the cheerful narrator. "Has he learned?"

Also on display is one of those transgenic mosquitoes, altered so they can't carry the parasite that causes malaria in humans. In 2009, 3.4 million such sterile male mosquitoes were released in the Cayman Islands to test their anti-malarial efficacy.

The mosquitoes, says Pell, were the first transgenic creature designed to thrive in the wild. But while such projects are controversial, most debates on transgenics involve agricultural uses. Transgenic foodstuffs are engineered for traits like higher yield and drought resistance. Supporters cite research holding such foods to be safe, and say they're necessary to ensure people are fed in the face of population growth and climate change. Critics contend that doubts remain about the risks genetically modified organisms pose to human health, and their ecological impact. GMO crops have been linked to higher herbicide use and cross-pollination of non-GMO crops, a threat to biodiversity.

Nations from Peru to Japan have banned imports or exports of GMOs, and the European Union requires that GMO foods be labeled. The U.S. has no such ban, and California just rejected a labeling referendum. In fact, most soy and corn grown here — the nation's two largest crops — is transgenic.

Humanity's history of harming nature with agriculture is extensive. Beef cattle trample the Great Plains where bison once roamed. Heedless farming sowed the 1930s Dust Bowl, and today's agricultural runoff causes "dead zones" in the Gulf of Mexico and elsewhere.

But the Center for Postnatural History is less about airing debates than it is about artfully documenting the simple pervasiveness of human-altered life-forms. The Center is open just four hours most weeks, on Sundays. Most of its traffic arrives during Penn Avenue's monthly art crawl, Unblurred. But Pell says that by-appointment visitors — sometimes by the busload — have come from as far away as Toronto. The Center is even listed as an "offbeat tourist attraction" on popular website RoadsideAmerica.com.

At Dec. 7's Unblurred, Pell will unveil a new exhibit featuring rodents from the Smithsonian Institution that were exposed to radiation during and after the Manhattan Project. Pell photographed the taxidermied mice during a research trip. They're all pretty normal-looking — visually, at least, they're better off than the transgenic mice the Center now depicts in two giant x-rays, which were bred, respectively, to have too many ribs or none at all.

Visitors often ask Center staffers whether they're for or against post-natural life. Pell replies that the field's too broad to say. "You have to take everything on a case-by-case basis," he says.

Besides, he adds, a museum can't spur real reflection if visitors are merely responding to the institution's own adamant point of view. "What we want," he says, "is for people to wrestle with these problems on their own terms."