That time when baseball players rebelled by forming their own league

Bob Ross’ The Great Baseball Revolt chronicles the little-remembered circuit’s lone season, in 1890

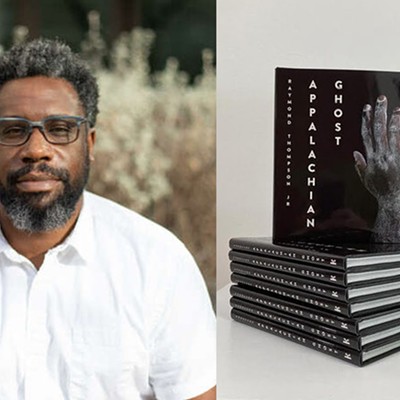

Author Bob Ross

[

{

"name": "Local Action Unit",

"component": "24929589",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Bob Ross would like to tell you that the subject of his new book was a life-long preoccupation, but it was more of a serendipitous accident. The Point Park University professor of global cultural studies was researching the 1856 Republican Convention, which was no doubt thrilling, but just wasn’t engaging him. “I was bored researching it. So bored,” Ross said with a laugh when he sat down with City Paper. As a respite, he looked through some old Baseball Encyclopedias. “I came across a short paragraph about the Players League, which I had never heard of before. Honestly, from that moment to when I finished the book, I enjoyed every minute of it. It was a thrill,” he said.

Released this spring by the University of Nebraska Press, The Great Baseball Revolt chronicles the rise and fall of the short-lived Players League, which existed for only one season. In the spring and summer of 1890, the Players League competed with the established National League’s eight teams, including Pittsburgh’s Alleghenys, as well as franchises in Boston, New York, Brooklyn, Cleveland, Philadelphia and Buffalo. But the league also deserves a spot in the history of American labor struggles.

Ross sets the stage for the league’s formation by immersing readers in 19th-century baseball: the evolution of the game and codification of the rules; its growing popularity; the paternalistic, Victorian attitude toward both players and fans; and baseball’s development as a paying, professional endeavor, rather than an amateur pastime.

The game was slightly different then: A walk was granted after eight “called balls,” for instance, and a baserunner was out if hit by a batted ball. And the times were certainly different. Ross meticulously explores the conditions that led to the formation of the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players trade union. The Brotherhood, more akin to a skilled craftsmen’s guild than to the AFL-CIO, attempted to negotiate with the owners of the National League teams. But this was decades before federal law ensured collective-bargaining rights, and the club owners wouldn’t recognize the union, let alone sit down to find middle ground.

The key issue was baseball’s infamous “reserve clause,” which basically meant that the teams owned the players, at least insofar as their professional-baseball careers were concerned. “Whether contracted or not, players across the league were … completely immobilized,” writes Ross. “Without the ability to pit teams in competition with one another for their labor, players could not effectively use the power they held in their extraordinarily skilled bodies to determine the price of their labor.” It was either play for the club that “owned” you — at an artificially low salary — or play for no one.

In their revolt, the players were led by John Montgomery Ward, one of the finest players in the league and also armed with an Ivy League education and a law degree. He was equally at home on the diamond and speaking in front of large groups or writing op-ed pieces for newspapers.

Stymied by the owners’ recalcitrance, Ward and the players found only one avenue to redress their grievances — establishing their own league.

In some cities, the Players League didn’t do badly. In a few towns, in fact, it matched or surpassed the gate receipts of the National League franchises. But across the board, the profits were insufficient to make it sustainable.

Here in Pittsburgh, Alleghenys stars—including Hall of Fame pitcher Pud Galvin—jumped to the upstart club. But the Players League just never caught hold, Ross writes. First off, even the established National League club wasn’t very good, and baseball wasn’t as well-attended as in cities like New York and Boston. The Players League franchise, known as the Burghers, lacked sufficient local investors, and was the last team to secure a home ballpark.

Contemporary fans can probably relate to some of the other challenges the club faced. When the season started, the weather was rainy and dismal, which kept fans away in droves through most of June. And the team itself was pretty bad. “They were basically out of the pennant race by the Fourth of July,” said Ross.

Still, if nothing else, the Players League was well ahead of its time. After the league’s dissolution, in 1891, the reserve rule it had defied remained in place. It was still in effect eight decades later when, in 1969, Curt Flood famously challenged his trade from St. Louis to Philadelphia. Flood’s case went all the way to the Supreme Court, where he lost, but in the process paved the way for free agency.

Despite the Players League’s short life, Ross’ history shines a light on labor relations that glimmers to this day, as well as on the quest for agency and independence by professional athletes.

Released this spring by the University of Nebraska Press, The Great Baseball Revolt chronicles the rise and fall of the short-lived Players League, which existed for only one season. In the spring and summer of 1890, the Players League competed with the established National League’s eight teams, including Pittsburgh’s Alleghenys, as well as franchises in Boston, New York, Brooklyn, Cleveland, Philadelphia and Buffalo. But the league also deserves a spot in the history of American labor struggles.

Ross sets the stage for the league’s formation by immersing readers in 19th-century baseball: the evolution of the game and codification of the rules; its growing popularity; the paternalistic, Victorian attitude toward both players and fans; and baseball’s development as a paying, professional endeavor, rather than an amateur pastime.

The game was slightly different then: A walk was granted after eight “called balls,” for instance, and a baserunner was out if hit by a batted ball. And the times were certainly different. Ross meticulously explores the conditions that led to the formation of the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players trade union. The Brotherhood, more akin to a skilled craftsmen’s guild than to the AFL-CIO, attempted to negotiate with the owners of the National League teams. But this was decades before federal law ensured collective-bargaining rights, and the club owners wouldn’t recognize the union, let alone sit down to find middle ground.

The key issue was baseball’s infamous “reserve clause,” which basically meant that the teams owned the players, at least insofar as their professional-baseball careers were concerned. “Whether contracted or not, players across the league were … completely immobilized,” writes Ross. “Without the ability to pit teams in competition with one another for their labor, players could not effectively use the power they held in their extraordinarily skilled bodies to determine the price of their labor.” It was either play for the club that “owned” you — at an artificially low salary — or play for no one.

In their revolt, the players were led by John Montgomery Ward, one of the finest players in the league and also armed with an Ivy League education and a law degree. He was equally at home on the diamond and speaking in front of large groups or writing op-ed pieces for newspapers.

Stymied by the owners’ recalcitrance, Ward and the players found only one avenue to redress their grievances — establishing their own league.

In some cities, the Players League didn’t do badly. In a few towns, in fact, it matched or surpassed the gate receipts of the National League franchises. But across the board, the profits were insufficient to make it sustainable.

Here in Pittsburgh, Alleghenys stars—including Hall of Fame pitcher Pud Galvin—jumped to the upstart club. But the Players League just never caught hold, Ross writes. First off, even the established National League club wasn’t very good, and baseball wasn’t as well-attended as in cities like New York and Boston. The Players League franchise, known as the Burghers, lacked sufficient local investors, and was the last team to secure a home ballpark.

Contemporary fans can probably relate to some of the other challenges the club faced. When the season started, the weather was rainy and dismal, which kept fans away in droves through most of June. And the team itself was pretty bad. “They were basically out of the pennant race by the Fourth of July,” said Ross.

Still, if nothing else, the Players League was well ahead of its time. After the league’s dissolution, in 1891, the reserve rule it had defied remained in place. It was still in effect eight decades later when, in 1969, Curt Flood famously challenged his trade from St. Louis to Philadelphia. Flood’s case went all the way to the Supreme Court, where he lost, but in the process paved the way for free agency.

Despite the Players League’s short life, Ross’ history shines a light on labor relations that glimmers to this day, as well as on the quest for agency and independence by professional athletes.