Architecture has long had a paradoxical relationship with childhood and children. At least since Leon Battista Alberti construed architecture in the Renaissance as an erudite and scholarly enterprise, it has been a sophisticated pursuit, appropriate only for adults. Twentieth-century modern architecture, in the hands of people such as Mies van der Rohe, only exacerbated that sense, by draining the built environment of any remote scrap of fun or frivolity.

So how much of a surprise is it that architecture is newly a playground at the Carnegie Museum of Art — both as an installation in and a theme of the Carnegie International and through the Heinz Architectural Center's The Playground Project exhibition? Beyond a subject matter or building type, it is part of a larger rumination about opening doors, expanding audiences and making the place more accessible to children and other everyday people. For the versions of architecture and art that aim to be social and non-elitist, these are admirable goals indeed.

At least that's what I keep telling myself. Alas, I feel the same way about children that I do about architecture: I can really trouble myself to interact with only the very best examples. And yet, though "You kids get off my lawn" may be a personal mantra, it is hardly a valid exhibition critique. Both the quality of the exhibition and the revised cultural outlook that it represents need careful consideration.

Happily, The Playground Project — a collection of 2-D displays, video documents and actual play spaces, guest-curated by Gabriela Burkhalter — establishes itself in historical and aesthetic rigor. Playgrounds themselves have roots in scientific approaches to child development, as epitomized by psychologists Jean Piaget and Bruno Bettelheim. Simultaneously, the tendency of some branches of Modern art, whether Surrealism or art brut, to value child-like expressions of naïveté, means that artists such as Isamu Noguchi convincingly blend real fields of play with the discourse of the art world.

Likewise, certain architects have made playgrounds a specialty. Aldo Van Eyck might be the most renowned for his work in Amsterdam, where his hundreds of designed playgrounds reflect the particularly Dutch version of humanization in architecture — practical, hands-on vignettes in the city that still make reference to Dutch modernist art. In this show, Van Eyck's playgrounds are shown through period photographs.

Arguably these tendencies to blend the interests of modern art and childhood play reach a particular culmination in Tezuka Architects' work, which is both elegant and conducive to play. Their ring-shaped Fuji Kindergarden is a one-story pavilion with an open plan and an occupiable roof, complete with perforations to accommodate pre-existing trees. It is conceptually recreated in the Heinz Architectural Center's largest exhibition room with hanging fabric screens that both echo the building's shape and allow video images of the structure's frolicking kids to be projected, along with a soundtrack of laughter and squeals. Within the fabric-enclosed volume are scores of white balloons for kids to kick around to recreate the play of the original building.

OK, kids, get on my lawn. If Tezuka Architects can find the alchemy in restrained and seemingly effortless architecture that appeals to both aesthetes and kids, then I am all for it.

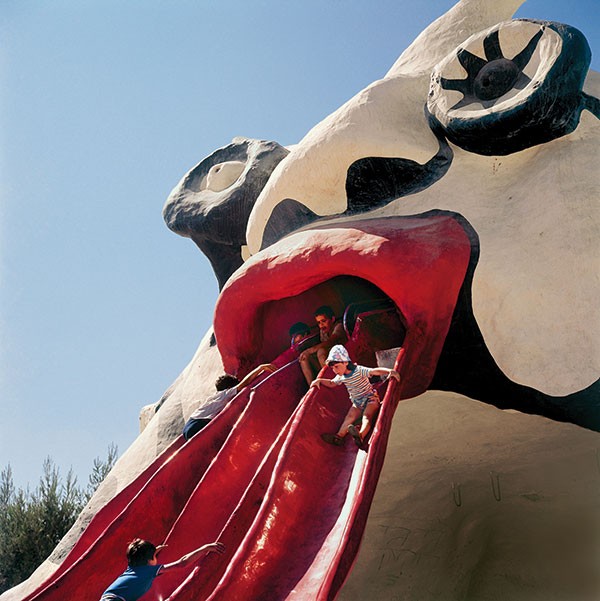

In fact, the Lozziwurm, the newly installed playground piece originally created by Yvan Pestalozzi in 1972, seems forced and garish by comparison. A new piece by Tezuka would probably have been more elegant and more likely to save the trees that were felled to accommodate the Lozziwurm. Or why not something more zoomorphic by that perennial favorite, the late Niki de St. Phalle? Or Richard Dattner, whose interlocking, three-dimensional building tiles, on display at the HAC, compellingly link grown-up and child-like architecture?

Likewise, go ahead, bring kids into the Heinz Architectural Center. Turn a large part of it into a concept-based playspace, and let them run, kick and yell. But in an exhibit in which play spaces through the decades by real masters, both familiar and obscure, crowd each other for attention, you can indeed have too many sandboxes and too many drawings by randomly selected third-graders.

Perhaps most tellingly, the pervasive use of plywood as background for the exhibit's drawings and images seems like a heavy-handed misstep. When the aim is to find renewed harmony in the architectural interests of children and adults after too many occasions of divergence, surely the multi-colored plaster walls of the Heinz Architectural Center could be reconceptualized as kid-friendly polychromy, rather than covered over. The forceful masking of these potentially sympathetic walls is no better a treatment for architecture than it would be for children. The best of these works show that balance is to be found in open-hearted and conciliatory approaches from all perspectives, not overcompensation for previous errors.